New Conflict Resolution Program Aims to Shift Bowdoin's Culture

By Rebecca Goldfine

The initiative, which launched this fall, uses alternative dispute resolution techniques, including restorative justice and dialogues, to help find solutions for cases that don't require administrative action or hearings in front of the Conduct Review Board.

Instead, PNVCR's student and staff facilitators "offer a myriad of pathways—each adaptable to the needs of the individuals involved—to help members of the Bowdoin community learn how to manage and resolve conflict peacefully, as well as gain an understanding of the impact of their actions," according to its website.

"There's a desire at Bowdoin to use these restorative processes more because they build community, establish community standards, and respond to harms," said Director of Residential Education and Assistant Dean of Student Affairs Whitney Hogan. Hogan has been instrumental in introducing the concept of restorative justice to Bowdoin.

Though PNVCR was formalized this semester, alternative practices to address cases outside the scope of the Conduct Review Board have been common on campus for several years. Residential Life, in particular, has used facilitated dialogues and other tactics to help quarreling roommates and other students find common ground.

The change now is that the program has been formalized and expanded. Currently, more than fourteen staff, faculty, and students have been trained to lead their peers through disputes. The group is actively taking requests and referrals from across campus.

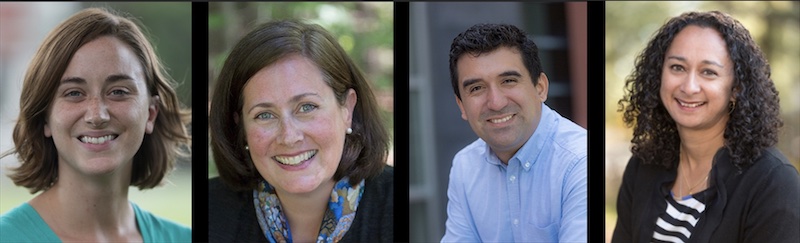

Four directors oversee the program. Alongside Hogan, Associate Dean of Student Affairs and Community Standards Kate O'Grady, Director of the Rachel Lord Center for Religious and Spiritual Life Eduardo Pazos, and Stanley F. Druckenmiller Professor of Chemistry and Environmental Studies Dharni Vasudevan are overseeing the program.

They hope that the new program will, in time, bring change to the College on a broad scale. "We are working to integrate this into the fabric of the Bowdoin community so that it becomes the preferred method for addressing conflict," said O'Grady. "We want it become part of why somebody might want to be at Bowdoin."

Hogan echoed this vision. "If we do this well, it will permeate lots of different areas," she said, from easing roommate misunderstandings to finding solutions to disagreements between colleagues.

PNVCR is multi-pronged, with some efforts meant to address harms and others designed to prevent them. The facilitators offer one-on-one conflict coaching, in which they will consult with managers and others in leadership to improve their communication skills and management strategies.

Additionally, if a rupture occurs on campus or beyond Bowdoin, or disturbance around a broader social issue, community discussions can be organized in response. For its first community circle, on Oct. 1, PNVCR invited students to discuss anonymous speech and social media.

While the program means to help people at every level of the college, in practice, it will be most active with students, since they make up the biggest population on campus. The directors stress that the new practices do not replace Bowdoin's traditional means of addressing violations of the academic or social code.

Restorative justice and conflict resolution practices can, in certain situations, replace more traditional means of applying justice, such as when a body of people or a judge decides a wrongdoing has been committed and metes out a punishment. In these cases, a violator is often removed from the community—most likely, they're sent to jail or expelled from school. Restorative justice, alternatively, is meant to keep people tethered to their community and social groups intact.

Restorative justice — Increasingly common in schools, restorative justice helps offenders acknowledge the impact of their behavior. Facilitators guide them to find ways to repair the damage and hurt they've caused.

Facilitated dialogue — A structured conversation, usually about difficult or sensitive matters, between two or more parties involved in a conflict.

Restorative dialogue — A more structured form of facilitated dialogue with a specific outcome or resolution.

Shuttle negotiation — An indirect form of mediation for parties who can't be together in the same room, due to no-contact orders or because feelings are so heated. Mediators communicate the needs and opinions of the people in dispute through an exchange of letters, for example, which are written and read with facilitators.

"The Conduct Review Board [which hears cases of alleged violations of the College's Academic Honor Code and Social Code] still exists, and whenever an issue should be handled through them, it will be handled through them. But there's a whole set of issues that do not rise to the level of the conduct displinary action measure," Pazos said. "And that is where our program steps in."

For example, vulgarity or rudeness might not trigger involvement by the Conduct Review Board, but nonetheless can "make the community a bit more frayed or less knitted together," Hogan said. Other situations that can drive wedges between people could include a slur written on a whiteboard, a comment made by a student who's had too much to drink, or a spat between roommates on anything from dirty laundry to political opinions.

Hogan says the program has already had many successes, especially in the realm of residential life. Proctors or residential advisors will often learn of tensions between roommates when they receive a request from a student who wants to be relocated to another room. "Rather than do that, a proctor or residential advisor will lead a facilitated dialogue," Hogan said. "And most people end up staying."

In the process, those roommates will likely have learned ways to communicate and resolve differences, and—depending on the situation—come to a deeper understanding of why some statements or actions can be upsetting to people of different religions, races, or socioeconomic backgrounds.

Part of the drive to use alternative conflict resolution practices and restorative justice more broadly on campus is to make it a foundational element to a Bowdoin education, Pazos said. "We really believe conflict resolution skills are absolutely essentially for the globalized world we live in. As we talk about creating leaders for the next century, our students have to have those skills."

Inside of communities, whether they're in organizations, neighborhoods, cities, or countries, harm will inevitably happen. But there can be systems and procedures that heal that harm, repair that harm, and learn from it, and people can continue to be in community together. — Eduardo Pazos

How PNVCR works

Once the Program for Nonviolence and Conflict Resolution receives a request—which may come from an individual, a student club, an athletics team, or an academic department, etc.—facilitators will gather information about the case and chart the best course of action, whether that's a faciiltated dialogue or shuttle negotiation (see sidebar).

- Journey Browne ’22

- Elise Hocking ’22

- Graham Rutledge ’22

- Colby Santana ’23

- Souleman Toure ’22

- Peyton Tran ’22

They may also be asked to respond to bias incidents on campus. In that case, the aim is to help illuminate for the perpetrator how their actions have harmed others, even if the act was unintentional (like committing what seemed to be a silly prank). While the harmed person is always asked to participate, often they choose not to, O'Grady said. In this case, another person—an employee or student—stands in as a proxy for them in a facilitated dialogue.

In past cases at Bowdoin, restorative justice outcomes have included having students enroll in a course on race and racism, or read a book on the topic. O'Grady said one particular student had, since their restorative justice process, taken three classes that fit that category the last time she checked.

Hogan added that she's seen students, following the restorative justice procedure, become involved in campus groups that address violence against women or substance abuse, commitments well outside the agreed-upon resolution. "One of the unique things to witness is that when students are going through the restorative justice process, and we come up with an outcome like 'read a book' or 'write a reflective essay,' they often don't think it is enough," she said. "Once they understand the impact, they feel like the outcome isn't enough."

Yet, while perpetrators sometimes wish to overcompensate for their action, in many cases, the person who feels hurt simply wants an apology and to be heard, O'Grady said.

In the end, Pazos said restorative justice aims to avoid shaming offenders (although they often do feel guilt as a natural outcome of being caught violating norms). Foundational to peacemaking and nonviolence, he said, "is recognizing the inherent dignity that is in place in every single person who is part of a community. When you place people's dignity and personhood as central to the community, it's hard to see them as nonmembers. We act in very different ways when we uphold each individual's dignity as central to everything we do."