In Masculinities Summit, Men Discuss Friendship, Vulnerability, Accountability

By Rebecca Goldfine

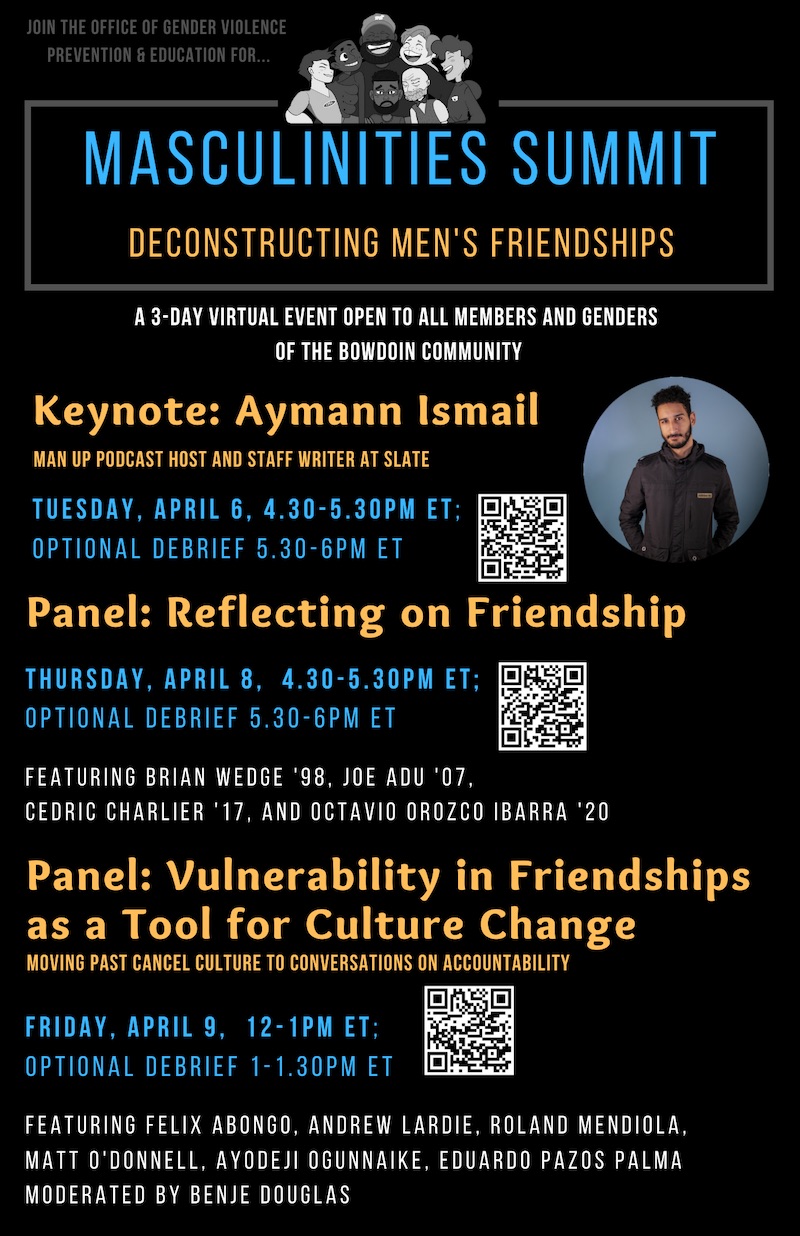

The Office of Gender Violence Prevention and Education launched the first Masculinities Summit in 2019, with the plan of hosting one every other year.

"The summits take a primary prevention lens to stopping dating and sexual violence," said Director of Gender Violence Education and Prevention Lisa Peterson. "We examine what some of the risk factors are that allow and enable violence, and think practically about shifting the cultural norms around behaviors that permit it to happen."

This year's summit was held virtually and was open to all. It brought together students, alumni, faculty, and staff "to discuss as a community the societal expectations of masculinity and to recognize gender realities," Peterson said.

She organized the summit with a team of four students: Vanessa Apira ’21, Ailish O’Brien ’22, Grace Carrier ’23, and Ahmad Abdulwadood ’24. They organized three main events—a keynote talk and two panels—around the summit's theme of "deconstructing men's friendships."

Below are brief summaries of a few of the points made during the wide-ranging discussions.

Manning up with Aymann Ismail

Keynote speaker Aymann Ismail is a journalist who hosts the podcast, Man Up, which looks at "masculinity, race, and relationships in the modern world."

"We were excited to have someone who is engaging in these ideas bring this conversation to campus," Peterson said. "We recognize the value of someone who is thinking about this from a journalistic and personal perspective. Because his work is so approachable and so centered in his own thoughts and experiences, everyone could find something to connect with and take home with them."

In his Zoom talk, Ismail spoke about the ways he's observed the pandemic straining male friendships, particularly those based on activities like watching or playing sports together. "As a journalist I thought this was interesting, so I did podcasts about the pandemic and how men were struggling to keep their friendships alive," he said.

He made the decision during the past year to reach out to his male friends for regular "wellness checks." "Community doesn’t just happen, you have to work on it," he said.

Responding to a student question about how he holds his friends accountable—for instance, letting them know if they've said something demeaning about women—Ismail said first and foremost, he holds himself accountable, and always strives to be better. "Hopefully by setting that example, others can learn," he said.

If he does feel called to speak with a friend about their behavior, he says he would try to avoid provoking a defensive reaction. So, he might couch his criticism as, "I know you didn't mean it that way, and you probably think it's innocent, but actually here's what you're saying when you call someone a 'B' word." Additionally, he might speak "about the growth that I've had to share what happens when I put aside my ego and try to be the best version of myself, and how gratifying that is," he said.

He also mentioned how important it has been for him to become sensitive to how he impacts social dynamics. "To be a man in the world comes with privilege, and what you do with that privilege is more important than anything else," he said.

In practice, this means being aware of when you're being loud, taking up space, and imposing your ideas or ideals on others. "That just creates a vacuum for women. You don't ever want to take the power away from someone, you want to be able to pass the power on."

Ismail finished his Zoom meeting with the advice, "Say I love you to your best friend."

Reflecting on friendships

For Thursday and Friday, the summit team put together two panels, the first focused on male friendships and the second on accountability.

In the Thursday panel, three alumni—Brian Wedge ’98, Joe Adu ’07, and Cedric Charlier ’17—each invited a friend to join them. Respectively, these guests were Todd Richards, Michel Bamani ’08, and Patrick Toomey ’17.

AJ Bravo ’22 and Isaac Cooper ’23 moderated the discussion, opening with a question about what the panelists viewed as their responsibilities to one another and to their friendships. The men mentioned that providing kindness, loyalty, honesty, empathy, and support was critical. "I don't think there's more that one friend can do for another friend than just offer pure support," Richards said.

The conversation also touched on how their close male friendships allow them to be vulnerable with one another, making it possible "to be their whole selves," Bamani said.

Qualities like vulnerability and honesty in a relationship can also make it easier to make repairs—to say you're sorry or to offer forgiveness when called for, Wedge added.

Several also mentioned that their friendships have deepened and become closer over time, especially as they have shared more life experiences, such as having children, experiencing loss and death, and finding their way in their careers.

Throughout these life changes, friends can provide not only support, but also enable internal shifts. "I find myself looking for people who make me better and push me to be a better person," Charlier said. "There is a certain kind of pressure to grow that you can only get from your friends."

Friendship as a Tool for Culture Change

On Friday, a panel of faculty and staff spoke on Zoom about "vulnerability in friendships as a tool for culture change," Vanessa Apira said.

Benje Douglas moderated the panel, which included Felix Abongo, Andrew Lardie, Ayodeji Ogunnaike, Matt O’Donnell, and Eduardo Pazos.

Douglas quickly zeroed in on the notion of accountability, asking each of the panelists to reflect on what it means to them and how they keep themselves accountable—and who—as well as how they hold other men in their lives to a standard.

"You know, we're living in a culture where the worst thing possible is to be wrong, to be corrected," Abongo said. "People look at it as being attacked rather than as an opportunity to grow and become better as a whole human being."

Having trust—and preferably also love—in one's relationship makes it easier to point out where your friend may have taken a misstep, without defensiveness getting in the way of change and growth, O'Donnell said. "It's important when you're trying to hold someone else accountable that it doesn't heap further shame on them," he added.

"Appeal to love," Ogunnaike added, "because love always brings people out of themselves and disarms the ego."

Douglas also asked the panelists to comment on the link between accountability and "cancel culture." "One of the things that is hard about cancellation, as we talk about it now, is this idea that if someone makes a mistake, there is no way back from it," he said.

O'Donnell argued that cancel culture tends to be self-defeating, as it eliminates the possibility for self-growth and the growth of others. "We need to allow people to make mistakes, to become educated, to grow and become better."

Indeed, cancel culture actually makes it more difficult to hold people accountable, Ogunnaike argued. "Accountability is about trying to draw people back into the community; it's about strengthening relationships and making them healthier and more positive," he said. "What troubles me about cancel culture is that I don't feel it shows a lot of love or a desire to bring someone back into the fold. It almost feels like a desire to demonstrate that the person is out."