Construction, Climate, and Forest Management

By Rebecca Goldfine

Starting in early March, the College will remove or trim six to eight unhealthy trees along Bath Road for safety reasons and will also take down a number of trees on campus to clear ground for the new Barry Mills Hall and the new John and Lile Gibbons Center for Arctic Studies, replanting with even more trees that are better adapted to Maine’s changing climate.

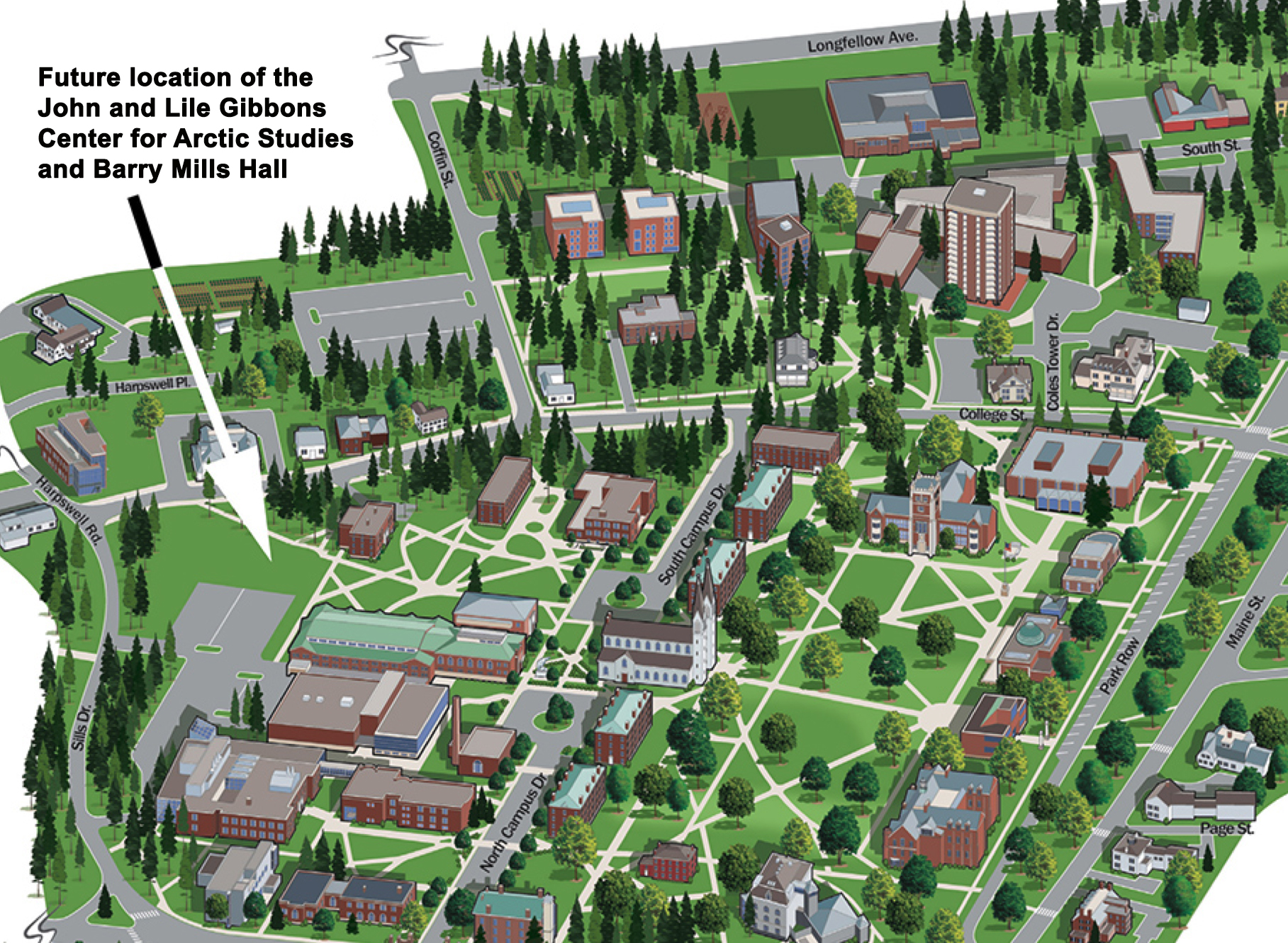

Work to prepare the site for construction has already begun, according to Matt Orlando, senior vice president for finance and administration. The new structures will be located near the corner of College Street and Sills Drive, on a portion of the parking lot behind Smith Union known on campus as the “Dayton lot.”

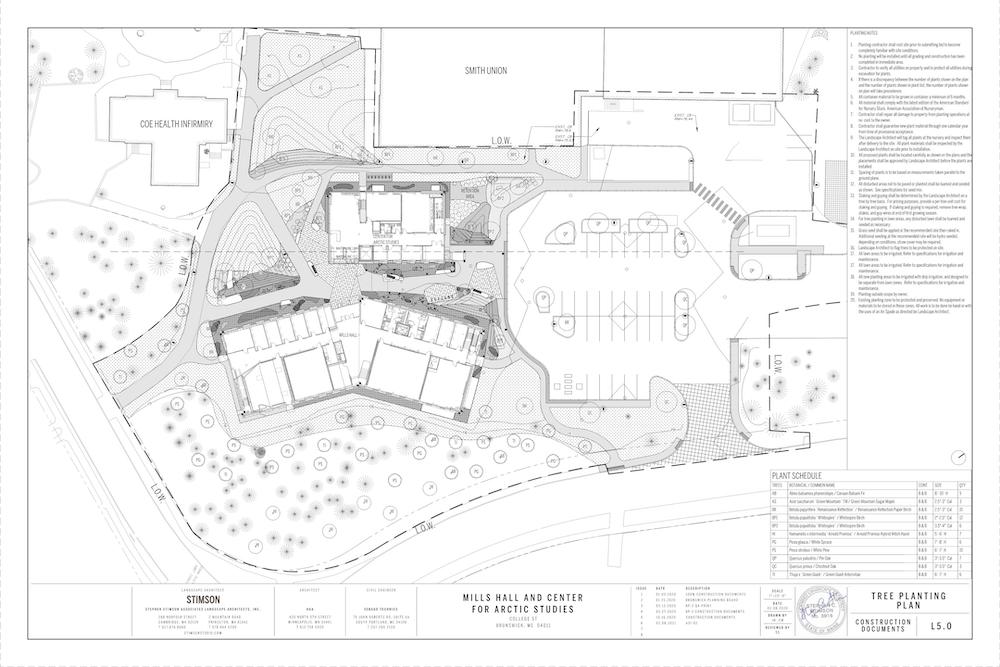

Sixty-eight trees in that area will be taken down and sent to Hancock Lumber to be milled into pine boards. Once construction is completed, eighty-five new trees will be planted, or 1.25 new trees for each tree removed.

All but two of the trees slated for removal on the Mills/Arctic Studies site are white pines that were planted in the 1940s. The planting strategy seeks to increase the biodiversity and create a healthier canopy by combining several different native evergreens with a mix of native deciduous trees. New plants will include a variety of evergreens—pine, spruce, and white cedar and a mixed deciduous species including pin and chestnut oaks, native birches, witch hazel, and winterberry.

"The variety of species will be more resilient to climate change than an in-kind replacement of white pine," said Orlando, noting that climate change will usher in warmer, drier seasons in Maine that will stress plants not adapted to those conditions.

In addition to the tree work planned for campus, Bowdoin is collaborating with the Town of Brunswick and Central Maine Power to identify and remove stressed or dead pines along a stretch of Bath Road that runs east, away from campus toward Cook’s Corner.

“The trees identified are structurally compromised, big, and at risk of falling into the Bath Road or onto the powerlines when they go,” said Jeff Tuttle, Bowdoin’s director of facilities.

These trees are part of an area known as the Bowdoin Pines, and many of them have come to the end of their lives.

"We have had a lot of blowdowns there whenever there have been high winds," Orlando said, observing that ice storms also threaten the feeblest trees. "That is cause for concern with passing vehicles, bicycle riders, and pedestrians in the area, and it is also disruptive to power continuity and the flow of road traffic.”

Planting young trees could also have an environmental benefit. Though towering old trees store a lot of carbon dioxide, younger trees remove more carbon dioxide more rapidly from the atmosphere, says ecologist Vlad Douhovnikoff, an associate professor of biology at Bowdoin.

“You have greater rates of carbon uptake in juvenile trees because they grow faster,” he said. “There is the highest rate of productivity in a forest when trees are rocketing up and trying to capture the canopy.”

That said, Douhovnikoff says it's important to consider the carbon that is safely sequestered in felled trees. He recommends milling them for planks, because “lumber is a great solution for long-term storage of carbon.”

The Future of the Bowdoin Pines

As the College evaluates which trees should be removed for safety reasons, it is taking a closer look at the entire thirty acres of the Bowdoin Pines, a forest made up of many older trees.

When forestry pioneer Austin Cary, Class of 1887, devised a plan for the Bowdoin Pines in 1896, he advocated that it should be managed according to scientific forestry principles, including harvesting trees for timber. In those days, white pines were thought to have greater commercial value than other pines because they grew well in Brunswick's sandy soil.

Austin Cary was "a pioneer in the modern science of forestry and a landmark figure in the history of the paper pulp industry," writes author Charles C. Calhoun in his 1993 Small College in Maine: Two Hundred Years of Bowdoin. Photo from the School of Forest Resources and Conservation.

But the majority of the white pines in the stand, which have life spans of 100 to 125 years, were never harvested. Even after the Bowdoin Pines was designated an official tree farm in the late 1940s—with a College forester hired to cultivate it—it is largely believed that the trees were never cut.

So, over the years, the forest has gone its own way. Many of the noble old pines have died and collapsed as part of the forest life cycle, but the trees present a hazard when they fall across the road or the train tracks, impeding passage and causing delays.

“Without any active management, natural succession is occurring,” Orlando said. “That has not necessarily been bad for the habitat and soils as old trees fall and new, mostly deciduous trees have taken root. But we need to make sure we fully understand what opportunities exist for preservation and management of the white pines going forward.”

Orlando said the College will be taking “a fresh look” at the Bowdoin Pines—with the help of landscape architects, environmentalists, and arborists—to possibly identify and then manage a zone with the best specimens to foster regrowth of white pines.

Douhovnikoff agreed that a plan of action would be beneficial for the forest and for the town. “Right now, we have a hands-off approach to the Bowdoin Pines, which is better than cutting it down and developing it. But doing nothing is a poor management approach,” he said. “I think there are better uses for that ground, both from a conservation and environmental initiatives standpoint.”