How iPads Made This Semester So Much Better

By Rebecca Goldfine

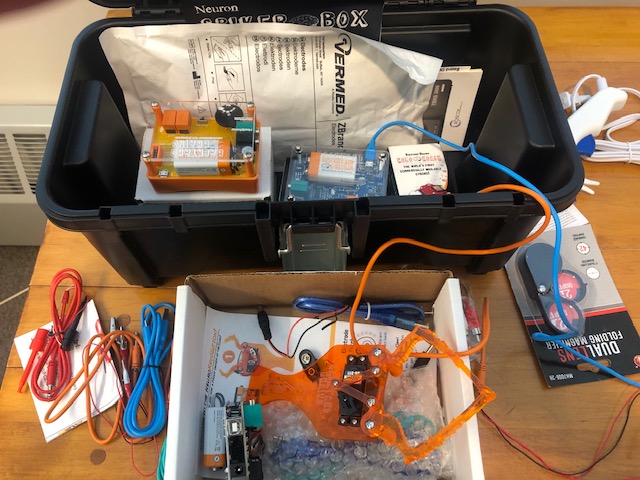

Bowdoin made the decision this summer to equip every student (and every professor who requested one) with an Apple iPad Pro, an Apple Pencil 2, and the Apple Magic Keyboard to ensure an equal learning experience for all. For those students with unreliable internet access, the College also paid to activate their iPad's cellular and Wi-Fi connectivity.

The recommendation for widespread adoption of iPads came from the faculty-led Continuity in Teaching and Learning Group after it reviewed outcomes from last spring's unplanned experiment in remote teaching. The group stressed that the technology would be particularly helpful for chemistry, math, physics, economics, and languages that don't use the Roman alphabet.

But faculty across the curriculum have made use of the device, and have been offered training and resources from Bowdoin's online learning and teaching (BOLT) group on how to incorporate the technology.

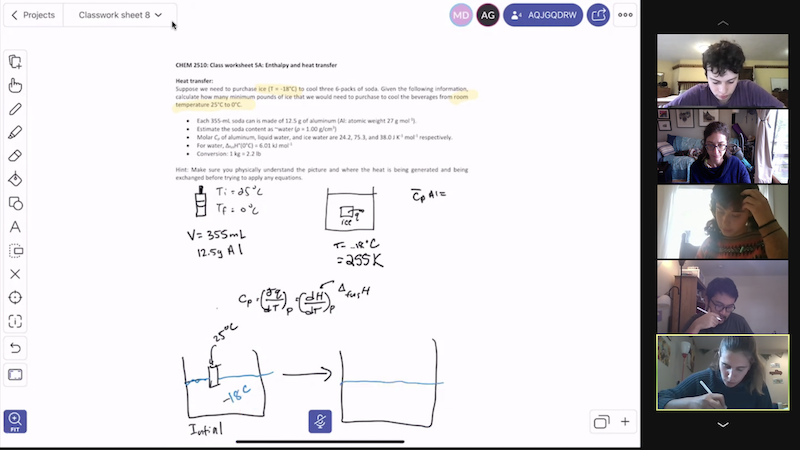

Kana Takematsu, assistant professor of chemistry and biochemistry, said she didn't think she could have taught the course Chemical Thermodynamics and Kinetics without iPads. In thermodynamics, students apply math and chemistry concepts to describing the physical world.

"It is a quantitative-based course, and the idea of not being able to see the students' thought processes or their work would have really restricted my teaching," Takematsu said.

"Last semester, I saw inequity," she continued, "between the students who could talk with me and draw at the same time versus students who didn't have that and had to send me a photo. It was like Pictionary with scientific concepts—that is sometimes a fun game, but sometimes it is really painful!"

Takematsu has also observed this semester that iPads have helped build community among students in her class. In real time, pupils are able to break into small groups to puzzle together over chemistry problems.

Biochemistry and math major Eva Verzani ’21, who is one of Takematsu's teaching assistants, said she can't imagine doing her job without iPads.

"In my TA sessions, I use the iPad a lot. I'll put together a whiteboard on Explain Everything, and it's really great because you can have everyone in the TA session—sometimes up to twenty kids—working on the same whiteboard." Albeit, she confessed, it can get messy at times with lots of scribbles and numbers representing many minds at work.

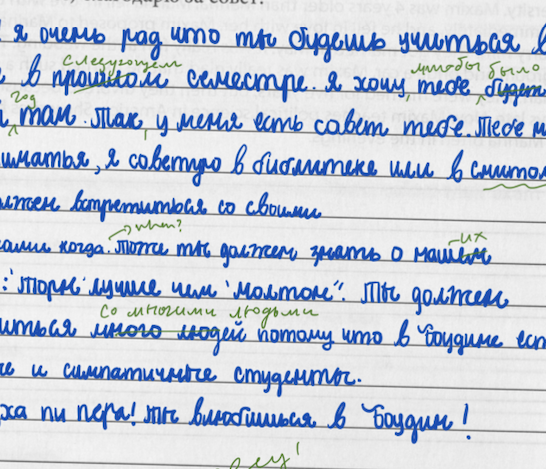

The iPads have also come in handy for Russian, Chinese, Japanese, and Arabic classes.

The Russian department doesn't teach students how to use a Russian keyboard until their third year, both because learning to type in Russian is difficult and because the faculty believe it's important their students master handwriting in Russian.

"Russia clings to handwriting," Russian lecturer Reed Johnson explained. "Students are still taught to write in cursive, and the Russian bureaucracy runs on handwriting. At the police department, you'll write out a statement in ballpoint pen and sign it."

When teaching online last spring, Johnson said the process of swapping assignments back and forth got a bit unwieldy. He would mark up a student's worksheet by hand, scan it, and email it back to them. "It was so time-consuming," he said.

These days, students share their assignments with him on Blackboard—Bowdoin's academic content management system—and he writes directly on the screen/sheet with his iPad pencil.

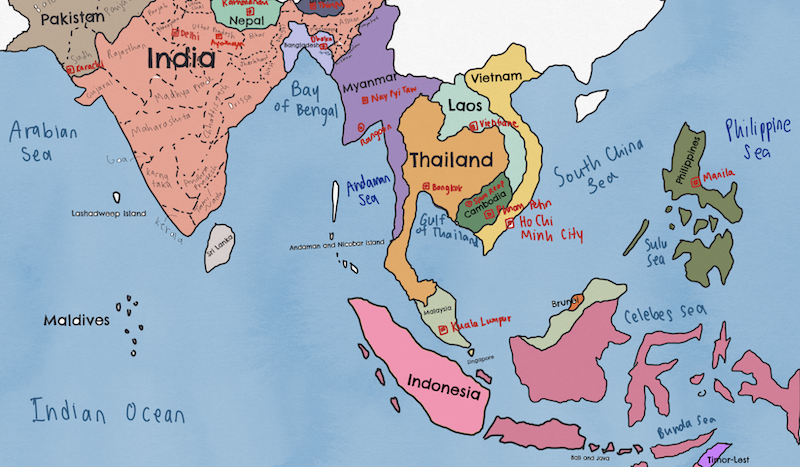

For one of his lessons on geography, Johnson also asked his students to use their iPads to draw maps of a made-up country. "They drew their own country with bays, mountains, ports. It was a little childish but really fun!" he said. "It was compelling for them to create their own world in another language."

Economics faculty are also finding the iPad useful. "In the economics department, we do a lot of work with math, solving long equations by hand and drawing graphs," Assistant Professor of Economics Matthew Botsch said in a video he made about how he uses iPads in class. "Replicating an experience we usually do on a whiteboard or chalkboard online was really important."

Beyond serving as a communications channel, iPads have also likely had an environmental impact. "I have used no paper this semester, and my students aren't using any paper either," Associate Professor of Economics Erik Nelson pointed out.

Nelson suspects that digital writing in academia will supplant writing on paper eventually, remaining in place well after the return to in-person teaching. "Bowdoin has sustainability bona fides already, but this might really reduce paper use," he said. "Even those people who two years ago said there would be no way they wouldn’t use good old-fashioned paper, they might change."

Yet, while the need for paper in classes and offices will probably continue to drop, other uses for paper—especially for mail deliveries—will likely increase. "But on this campus, at least within our small economy, the idea for how we use paper will have permanently changed," Nelson said.