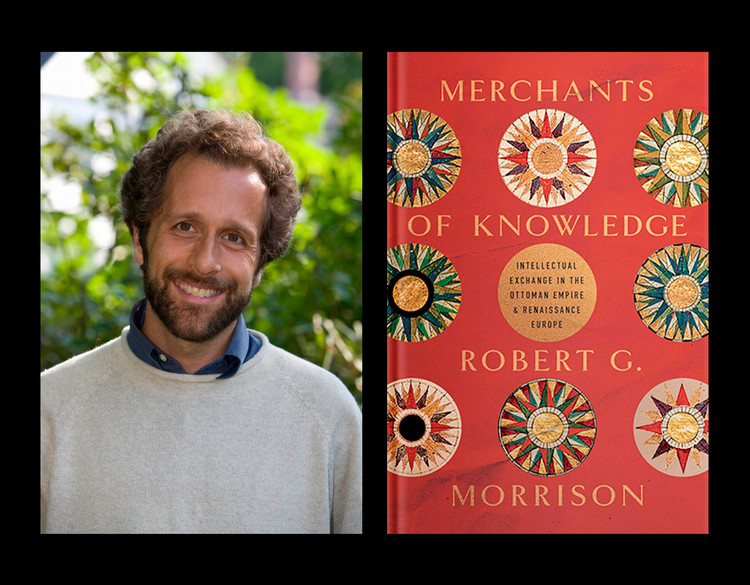

Robert Morrison Awarded Guggenheim Fellowship to Study Islamic Influence on the Renaissance

By Tom Porter

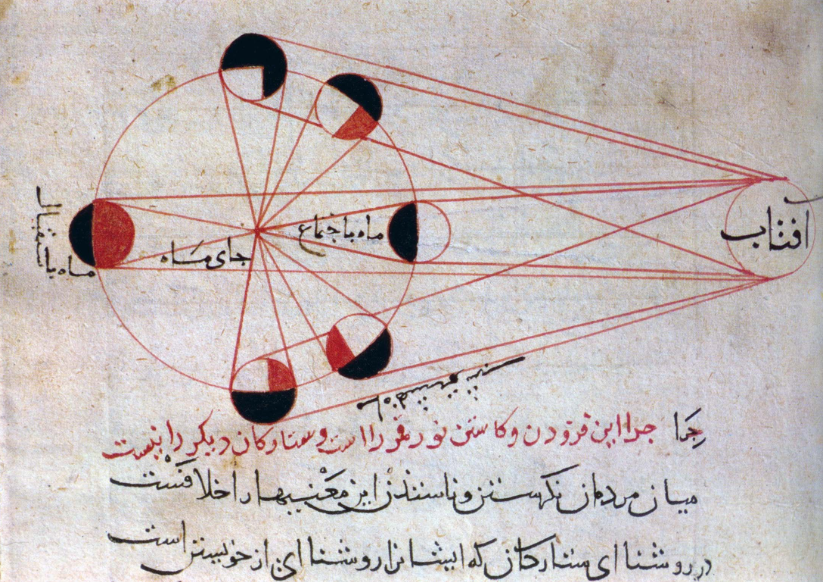

The Renaissance is often thought of as a uniquely European event: a late medieval cultural rebirth led by the city-states of modern day Italy, as artists like Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo drew inspiration from the ancient world in their sculptures and paintings. The Renaissance was also a period of great scientific advances, however, and it’s in this area, said Robert Morrison, where the contributions of scholars from the Islamic world have not been sufficiently appreciated or understood.

He’s one of 173 fellows chosen from a group of almost 3,000. “My field is the history of science in the Islamic world, and for several decades one of biggest questions in that field has been the connection between the scientific culture of the Ottoman Empire and the science of the Renaissance,” he said.

“Around the turn of the sixteenth century, it’s pretty clear these Jewish scholars were transporting ideas and theories between these two centers of power via Venetian Crete,” said Morrison. The Ottomans were interested in European medical texts and technology, he explained, while Renaissance scholars in western Europe learned about theories of mathematics and astronomy from the Islamic world. “The Renaissance is an even more complex phenomenon than many had thought,” he added.

One of the key figures in Morrison’s research is a Jewish scholar called Moses Galeano, who also wrote under the Arabic and Turkish name Mūsā Jālīnūs. “He was an extraordinary person, crucial because he truly straddled both worlds,” said Morrison. “He identified as a Jew but you wouldn’t always know it. He was extremely well informed and was familiar with the Ottoman court as well as elites in Venice. He brought some really high-level Islamic astronomy to Venice and Padua, but he also translated a Latin astronomy text into Arabic for a high-ranking Ottoman judge and wrote a text in Ottoman Turkish that reported on Latin medical texts.”

Morrison has uncovered new materials about this obscure figure, and the Guggenheim Fellowship will help him find still more during his sabbatical over the 2018-2019 academic year. The aim is to gain greater insight into how Copernicus and other Renaissance scholars learned about intellectual developments in Islamic societies. “Copernicus’ sun-centered arrangement of the planets is a mathematical transformation of late medieval Islamic astronomy,” said Morrison, “and the intellectual life of the Ottoman Empire was part of his intellectual context.”

My Love is an Anchor, 2004.

www.kategilmore.com

Kate Gilmore was the 2016-2017 halley k harrisburg ’90 and Michael Rosenfeld Artist in Residence at Bowdoin College. According to the Guggenheim Foundation’s citation, “Gilmore works between installation, video, and performance, creating work that seeks to attack the ways in which we perceive notions of strength, authority, and control in our social and political arenas.”

This flow of ideas between East and West was significant in other ways too, he said. “Ultimately, it’s all about trade. These Jewish scholars I’m writing about belonged to merchant families who worked the East-West trade routes, and it was this flow of commerce that led to the flow of ideas.” This was also important, he said, because it occurred at a time of great mistrust and animosity between the Turkish Empire and western Europe. “The Ottomans were a major military threat and people in the West were very scared of them,” he said, “which makes this exchange of intellectual capital all the more remarkable.”

When he learned he had won the fellowship, Morrison was keen to stress that “having senior colleagues and peers in the Department of Religion who set such a high bar in teaching and research has been a great part of being at Bowdoin.” Morrison’s colleague John Holt won a Guggenheim fellowship in 2014.