Revealing a more complicated/richer/diverse American Story: Fifteen Drawings gifted by halley harrisburg ’90 and Michael Rosenfeld

These questions recently came up in conversations with halley harrisburg ’90 and her husband Michael Rosenfeld, prompted by preparations for the upcoming exhibition of Bowdoin’s distinguished collection of drawings. Why Draw? 500 Years of Drawings and Watercolors will be the most comprehensive survey of this unique resource to date, and will be on view May 3, 2017 through September 3, 2017.

The curatorial team shared an early version of the exhibition’s checklist with halley and Michael, whose New York gallery has built a stellar reputation for groundbreaking exhibitions of American surrealism, social realism, and abstraction. The gallery’s special emphasis on African American art has contributed to major transformations in the way many museums and private collectors approach this long-neglected field. When halley and Michael scrutinized the list of works from the Bowdoin collection, they immediately identified several noteworthy gaps. Luckily, they were in a position to help.

In December halley contacted the curatorial team with the following email: “To assist your efforts and to hopefully strengthen your summer exhibition, Michael and I have been reviewing our holdings. We present to you an illustrated list of 15 works on paper for your consideration. … To be clear, we are presenting ALL of these works as GIFTS, and while some are not ‘big names’ … we selected the group to compliment, contrast, and reveal a more complicated/richer/diverse American story.” An attachment listed beautiful drawings by some of the greatest masters of American art of the twentieth century, including Romare Bearden, Paul Cadmus, Morris Graves, Nancy Grossman, Gaston Lachaise, Norman Lewis, Ben Shahn, Joseph Stella, and Pavel Tchelitchev, among others. The significance of this gift for the study of American art at Bowdoin is hard to overstate. It will be a delight to encounter the works in the galleries for the first time this summer and to know that they will be inspiring learning and enjoyment for generations to come.

The following four works offer a first glimpse at this generous gift.

Joseph Stella

American, 1877–1946

White Amaryllis, ca. 1920s

silverpoint and colored pencil

The Italian-American painter and draftsmen Joseph Stella straddled two worlds and developed two distinct idioms. Italian Futurism inspired him to celebrate American technological progress in iconic paintings of the Brooklyn Bridge. Increasingly disenchanted with modern advancements, he also created some of the most poetic and well-observed renderings of nature in American twentieth century art. In this closely-focused drawing Stella used the silverpoint, a method of drawing developed in the Middle Ages. The artist takes a silver stylus to coated paper, making marks by scratching lines into the uppermost layer. He then applied colors with colored pencil.

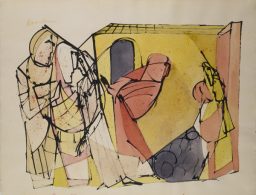

Romare Howard Bearden

American, 1911–1988

Nobody Knows You, 1945

watercolor and ink

This work is part of a series of watercolors dedicated to the passion of Christ. Presented in 1945 in New York’s Samuel Kootz Gallery, the exhibition was a breakthrough success and established Bearden’s career. Raised in Harlem, Bearden studied at Boston University and New York University and took classes with the German émigré George Grosz at the Art Students League. He became one of the most widely recognized American artists of the twentieth century. In this early work, created just after Bearden was discharged from the army, he simplifies forms and colors to make a statement about the human condition. Sources of inspiration are as far afield as Sienese painting of the Trecento (fourteenth century) and analytical cubism. Bearden admired the old masters: “Because, if a painter has certain rhythms going and these things are all done right, say five or six rhythms that interwind right, these things kind of expand even more.”

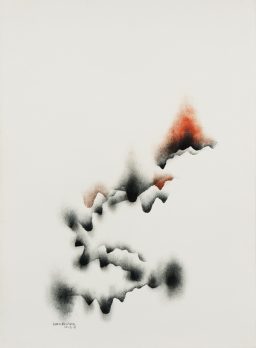

Norman Lewis

American, 1909–1979

Untitled, 1961

oil on paper

Lewis was an early pioneer of abstract expressionist painting, driven to overcome the constraints of representation with works that reference bebop and jazz as well as the history of African art. Lewis was active in the Civil Rights movement, and associated with and championed black artists, such as Romare Bearden and Jacob Lawrence, but sought in his work to transcend racial boundaries. Lewis’s delicate compositions sometimes appear suspended, as they unfurl in seemingly spontaneous gestures. Their linearity alludes to processions and might imply social movements as well as a range of emotions.

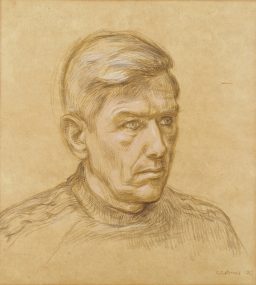

Paul Cadmus

American, born 1904

Self Portrait, 1963

pastel and crayon

Throughout his adult life, Cadmus exercised and strengthened his observational and artistic faculties by drawing. He often studied his face, which by all accounts, was especially handsome—and readily available to him. This regimen of daily drawing practice was not unlike the workouts of the dancers and athletes he admired and often portrayed. In his drawings, prints, and paintings, Cadmus celebrated the human figure, raising eyebrows for his implication of male homosexuality. While his large canvases sometimes bring forth the most private emotions, his most intimate work, such as this drawing, seems to be grounded in his conception of himself as a public persona.