Dante, Mathematics and Cognitive Theory Are 'La Dolce Vita' for Italian Prof

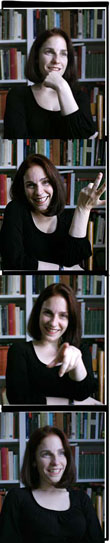

By Bowdoin NewsAnyone who thinks that Italian Medieval and Renaissance literature is dry and arcane has not encountered Bowdoin Associate Professor of Italian Arielle Saiber.

When she is not teaching about subjects such as love poetry in the Italian Middle Ages, the mafia and Italian stereotypes, or Italian Renaissance "how-to" manuals—Saiber is keeping up with experimental electronic music or thinking about code and theories of "space."

Her popular Web site, Dante Today: Citings and Sightings of Dante's Works in Contemporary Culture, celebrates all things Dantesque—including Dan T's Inferno hot sauce, an Italian audition notice for a new play, "Divina Commedia," and a New York Times book review of The Ancient Rain, a mystery featuring detective Dante Mancuso.

Students recognized Saiber's original teaching with a 2004 Karofsky Award for Junior Faculty. However, it is her groundbreaking scholarship on the relationship between the mathematical and literary imagination that is bringing Saiber international kudos—including a recent NEH fellowship and a one-year appointment as a fellow at Harvard's Villa I Tatti in Florence, Italy in 2008, an honor given to only 10-15 scholars a year worldwide.

Before heading off to Florence in the fall, Saiber met with Selby Frame, Associate Director of Academic Communications, to discuss the byways of her life as a scholar and teacher ... and how research into the geometry of language is leading her into surprising new explorations of neuroscience.

SF: What do people outside of academia say when you tell them you're an Italian Renaissance scholar?

AS: I get all kinds of reactions from people when they find out what I do for a living. When I was in grad school, people would say, "What are you going to do with a Ph.D. in Italian? I'd say: "I'm going to open a pizzeria, what else?!" [laughter] Too much to explain ... Italian language and culture are at the foundations of our western civilization. There is so much to study, to say, and to work with as a teacher and a scholar.

SF: Your wide-ranging intellectual palate is very much reflected in the courses you teach, which tend to celebrate Italian culture in highly original ways. You taught a course titled "Mona Lisa and the Mafia." This past year you covered everything from Renaissance love, cooking, etiquette, and guidelines for dying, in a course called "How To Do It," which studied "how-to" manuals of the Renaissance." Where do your teaching ideas come from?

AS: The Middle Ages and Renaissance in Italy lend themselves to really neat stuff. I've always been interested in "pop culture," as well as the fringe and avant garde of every period. I also find there is much that is stimulating, provocative and at times playful in the canonical literature. So my courses treat the canon, the "pop," and the "fringe" because I want students to see the material from all angles and hope that each student will connect with something and run with it.

SF: It does seem that la dolce vita is enjoying a new flowering or Renaissance in the American imagination as well— you see it in everything from The Da Vinci Code to The Sopranos, to the proliferation of Tuscan cooking adventures. How do you account for this?

AS: There is an immense love for Italian culture in this country and there has been for many decades—the food, the design, the art. Italy is often perceived as a world that openly expresses and gives primacy to love, passion, joy, and family comfort. Many people even associate something glamorous with the mafia, which, of course, is problematic.

The very sound of the language inspires a kind of happiness and energy. I've seen this again and again when teaching Italian. Students smile when they speak the language.

SF: How do you translate that love of Italian culture into a more "serious" study of Italian Renaissance literature, particularly the works of Dante—who has turned into something of a modern cult figure with your popular Web site, "Dante Today: Citings and Sightings of Dante's Works in Contemporary Culture."

AS: The subject material is a springboard for wonderful exploration—Dante's journey is universal and it is riveting. Like most literatures of most periods and most cultures, medieval and Renaissance Italian literature explores the human spirit, the human experience, the world around us, and what is perceived as divine mystery. When I read literature with students, I try to help them "be there" and experience the shock, horror, anger, amazement and delight that a person of the period would—as well as giving them space to react from the point of view of a 21st century American college student.

SF: Students often cite your classes as having prepared them really well for contemporary academics as well.

AS: Well, maybe it's because they see the joy in thinking deeply and critically about how ideas are expressed in language and literature. I use rhetorical theory a lot—classical tropes and argumentation, and have students think about how word choice and word orders matter. And why they matter in each given context. I like offering students tools they can use in their everyday and professional lives: when reading newspapers, listening to political speeches, writing a job application or grant proposal, etc.

SF: That critical fascination for language has brought you to some very interesting places in your own scholarship, notably, your research on the intersection between geometry and literature. Not a trajectory you would imagine for an Italian Renaissance scholar. How did that all come about?

AS: It probably started in high school. My best friend was a math genius and I wished I could peer into her brain to see how it worked—how she could do what she did so effortlessly and brilliantly. I thought, "Math should not be so challenging for some and so simple for others! It's just a language, it's got symbols and rules. What is going on here?" [laughter]

From a scholarly point of view, it's a pretty natural leap from mathematics to Renaissance literature. With the fall of Constantinople in 1453, an immense amount of Classical texts, including mathematical treatises, were brought to Italy by Humanist scholars eager to revive the philosophies and knowledge of Antiquity.

Mathematics took a new turn once unknown and forgotten theories of the Ancient Greeks came to light. When you pair that with Classical aesthetics, rhetorical theory, and the Christian doctrine of the Renaissance, you begin to see particular patterns recurring in all the arts—certain proportions, shapes, and motifs.

The relationships between Renaissance mathematics and art, music, and architecture are subjects that have been looked at in great depth and with good reason. But little has been done in terms of looking at Renaissance mathematics and literature. It is, in fact, harder to see the commerce between these two arts. How do you look at a page of text, with words lined up horizontally from left to right, organized into paragraphs and chapters, and see mathematical influences? Obviously, mathematics' presence can be discussed conceptually with regard to content, but can it manifest in other ways?

SF: Do you mean that a mathematical pattern might exist within textual works that we're not aware of? Some syntactical construction the author developed to reflect some pattern of divine order, for example?

Yes. A quick example can be found in a poem that was written in 1539 by mathematician Niccolò Tartaglia. He placed his solution to the cubic equation in an eight-stanza poem (plus a one-line coda), and in terza rima, a three-line rhyme scheme invented by Dante for his Divine Comedy. Tartaglia did this for a variety of reasons—to help him remember it; to make it harder for the competing mathematician, Girolamo Cardano, to understand it and use it; and to echo the "three-ness" of the cubic.

The Church was fascinated by trinities, by particular triangular shapes and proportions that supported readings of the bible. Tartaglia's use of threes for his poem is a fusion of aesthetic principles, mnemonic strategies, and mathematics, as well as an echo of Christian doctrine and symbolism.

I am interested in how Renaissance thinkers structured their literary works to conform to aesthetic, theological, and mathematical ideals. In this period, language, geometric form, and number fused at a deep conceptual level. I don't believe that this is the only period in Western history in which this happened, but rather that the Renaissance was particularly conscious and intentional about this dialogue.

SF: Is this what you will be working on at the Villa i Tutti?

AS: Yes, this is the core of my new book, tentatively titled, Well-Versed Mathematic in Early Modern Italy, 1450-1650. [Saiber's last book was Giordiano Bruno and the Geometry of Language (Ashgate Press, 2005).] I will be discussing six authors in the Renaissance—some who are primarily mathematicians, others who are primarily literary authors—who display strikingly clear examples of the intersection of mathematical and literary imaginations.

Ultimately, I want to understand how the mathematical imagination works and how the literary imagination works. While we do not know exactly where and how each takes place in the brain, they likely share some neural pathways. They seem to do similar things. For example, when a mathematical equation is solved, or a theory proved, they look like stories that unfold step-by-step. We all understand narrative flow in stories. Why, then, would most people consider math "harder" than reading or writing a short story?

My book will address these questions and offer a few, general responses given by contemporary cognitive theory.

SF: How do you balance teaching and writing?

AS: It is what most scholars at a liberal-arts college like Bowdoin contend with. Basically, you just do it. You finish one book, then immediately start research on another book. You also keep working on articles, conference papers, book reviews, etc. And you keep funneling what you are doing in your research into your teaching. To continue the momentum of research and have your publications be timely, waiting years for your next sabbatical isn't easy!

SF: That must make your Villa I Tatti fellowship extra sweet ...

AS: It's a very special thing to get and the experience promises to be extraordinary in every way. There will be people from art history, history, musicology, literature, religious studies, philosophy—not to mention dozens of inconceivably sublime libraries, and beautiful gardens for contemplation.

SF: I'm sure your students will miss you a lot. Buona fortuna and hurry back!

AS: Grazie.