Dates:

Location:

Becker GallerySelected Works

About

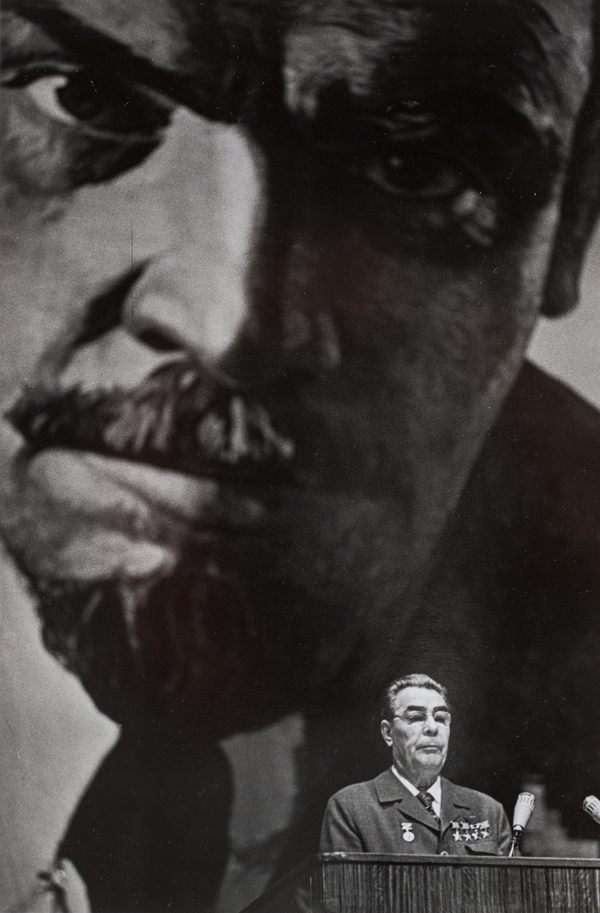

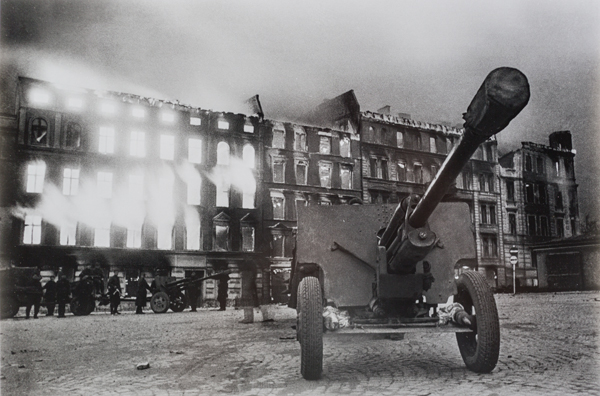

The distinguished Soviet photojournalist Dmitri Baltermants documented World War II and the following years of reconstruction in dramatic images that affected viewers in the USSR and around the world. Dmitri Baltermants (1912–1990) had graduated from the Math and Mechanics School at Moscow State University, with plans of teaching mathematics at the Higher Military Academy. Life drastically changed in 1939, when the Soviet newspaper Izvestiya sent him abroad to cover the Soviet-German annexation and partition of Poland and Ukraine. When Germany invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941, Baltermants was one of the first photographers on the battlefront. After the war, he worked for the Soviet illustrated magazine, Ogonyok, and in 1964 was named its photographic editor.

Many of Baltermants’s photographs were censored under Stalin and only became well known in the 1960s, in the era of the reform-minded leader Nikita Khrushchev. Even then, Baltermants’s images never presented an eyewitness account of combat or fulfilled their claim to objectively portray life in the USSR. Throughout his career, Baltermants altered many of his negatives to fit into the current Soviet ideology. He commented retrospectively, “In my time I was the leader of staged photography. I made some truly grandiose stagings.” Straddling the line between fact and fiction, his photographs served as an important form of state propaganda and reveal much about Soviet hopes and perceived challenges over the formative decades of the Soviet experiment. All of Baltermants’s photographs included in the exhibition are silver gelatin prints, printed in 2003.

This exhibition was curated by Johna Cook, Class of 2019, and supported by the Becker Fund for the Bowdoin College Museum of Art and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

This exhibition includes more than thirty of Baltermants’s most famous photographs and complements the concurrent exhibition, Constructing Revolution: Soviet Propaganda Posters from between the World Wars (September 23, 2017 through February 11, 2018). It is curated by Johna Cook, class of 2019 at Bowdoin College, who is double-majoring in Russian and Government.

Events

Gallery Conversation with Frank Goodyear and Johna Cook

November 16, 2017 | 4:30 PM | Bowdoin College Museum of Art

Frank Goodyear, co-director, Bowdoin College Museum of Art, and Johna Cook '19, exhibition curators, discuss works in the exhibition.

Lecture, "How an Uprising became a Revolution"

November 30, 2017 | 4:30 p.m. | Kresge Auditorium, Visual Arts Center

Semion Lyandres, professor of history, University of Notre Dame, discusses the first Russian Revolution that occurred in February 1917