A Hero Who Never Thought Himself a Hero: The Story of Henry L. Conway Jr. '51

By Andrea Becker '26The son of Henry L. Conway Jr. ’51 has established a scholarship fund to honor his father, a man who survived the odds to return from a Korean War prison camp, and who, forty years later, overcame his anguish about the war.

“Missing and presumed dead,” began the October 1952 letter from the United States Department of War to the family of Henry L. Conway Jr. Though Conway was unaccounted for, the US Marine Corp concluded that his survival was not possible, given the enemy assault on Outpost Detroit. They considered him to be one of the brutal conflict’s many casualties.

Inspired by heroics displayed by the veterans of World War II and the subsequent creation of the United Nations, the twenty-two-year-old had enlisted in the Marine Corps immediately following his graduation from Bowdoin in 1951. Mere months later, he would find himself facing fierce combat against overwhelming forces and horrendous conditions as a prisoner of war.

Back home in Baltimore, his father refused to believe that his only son was dead, despite family members’ pleas that he accept the inevitable. That faith was rewarded when, late one night in September 1953, months after the armistice had been signed, the phone rang at the family home. The caller, identifying himself as a reporter with the Baltimore Sun, said he was looking for a statement from the family. Miraculously, it had just been announced that among the last of the POWs to be released was Lieutenant Conway.

Following a joyful reunion with his family, Conway would go on to earn a law degree from the University of Maryland and begin what was to be a lengthy career as an attorney in Baltimore. He married Marilyn Litty and together they raised three children, two sons and a daughter.

Years passed and milestone events would come and go. Conway attended his twenty-fifth Bowdoin College reunion and his son’s graduation. All that time, he never spoke of Korea, though the images of what he encountered remained indelible in his memory.

Benjamin Conway, Class of ’86, recently sat down with a Bowdoin reporter to talk about his father’s bravery and experience as a POW and the newly established Henry L. Conway Jr. ’51 Scholarship Fund.

“Growing up, while I understood that my father had fought in Korea and had been a prisoner of war, I never truly appreciated how deeply it impacted him,” Ben said. “And, had it not been for the Veterans Administration, I might have never known.”

Approaching retirement, Conway enrolled to receive health care through the Veterans Administration. After becoming aware of what he had endured in Korea, the medical staff asked if he might be willing to meet with a VA psychiatrist. It would be those therapy sessions, and his recounting the horrors of the battlefield, that would ultimately enable him to break from the memories and emotional turmoil that had come to haunt him for all those years.

Henry Conway wrote about his experiences in Korea in a detailed letter published in The Outpost War, a book that chronicled the actions of the US Marines in Korea. It begins, “On October 6, we began to receive regular shelling. It was no longer intermittent but steady; one after the other.”

His platoon of twenty-three marines had been sent to relieve a squad that occupied an outpost forward of the main line of resistance. Sunk into dusty trenches with his men, Conway described two hours of a withering artillery barrage thundering down on the outpost. “It seemed to last forever,” he wrote, adding that the shelling had reduced the squad to seven, many of them gravely wounded. When the shelling subsided, waves of Chinese stormed the outpost. Out of options, Henry directed his radio man to call for a direct artillery strike on their position. “Most of the men were dead, and the rest, including me, would soon join them. We were in complete ruin,” he wrote.

Conway and three others, all badly injured, were then captured and taken prisoner. He would spend the following eleven months in a Chinese POW camp, where he would endure brutal interrogations, long periods of isolation, and torture. He turned to his courses in the classics at Bowdoin to keep his sanity and maintain some sort of mental acuity in those conditions. “He would concentrate on reciting the Greek he had learned as an undergraduate, and it would be those lessons that kept him from total despair,” Ben remembers his father saying.

“I have had a difficult time keeping those events from taking over my life,” Henry Conway would write. “I have thought of that battle every day since it was fought and have been very hard on myself because of the loss of life and my surrender.”

“But hope springs eternal. Although after forty years, peace comes slowly, I am determined to make peace with myself,” he added. “At the end, I believe he finally achieved that goal. It was a long time coming,” reflected his son.

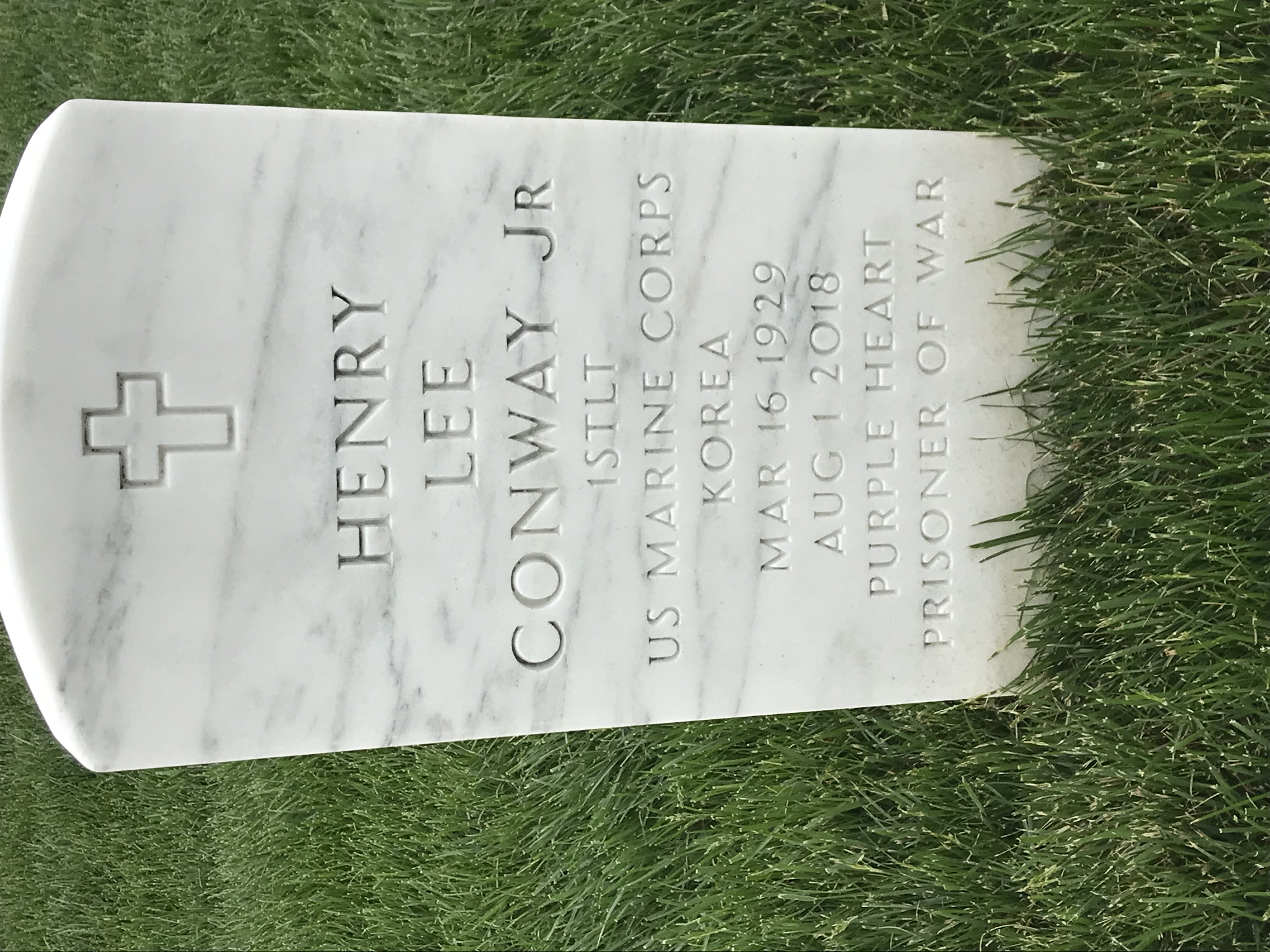

For his sacrifice, First Lieutenant Henry Conway was awarded a Purple Heart. He died August 1, 2018, at age eighty-nine, and was buried with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery. Ben described how touching it was as people along the processional route, who happened to be visiting Arlington that day, stopped to salute and pay their respects as the horse-drawn caisson bearing the flag-draped casket of his father passed. “Though he never considered himself one, he is a hero, not only to his family but to this nation. His burial at Arlington could not be more fitting.”

To commemorate his father’s service and valor, Ben established the Henry L. Conway Jr. ’51 Scholarship Fund to support students who attend Bowdoin from large urban public-school systems, with graduates of Baltimore City public schools having priority.