Lena Souffrant ’25 Brings New Ideas to Life in “Dead Bird Stories”

By Lily Echeverria ’26The show by the environmental studies and Africana studies major “challenges the entangled histories of science, colonialism, and ecological ‘discovery’ at Bowdoin College.”

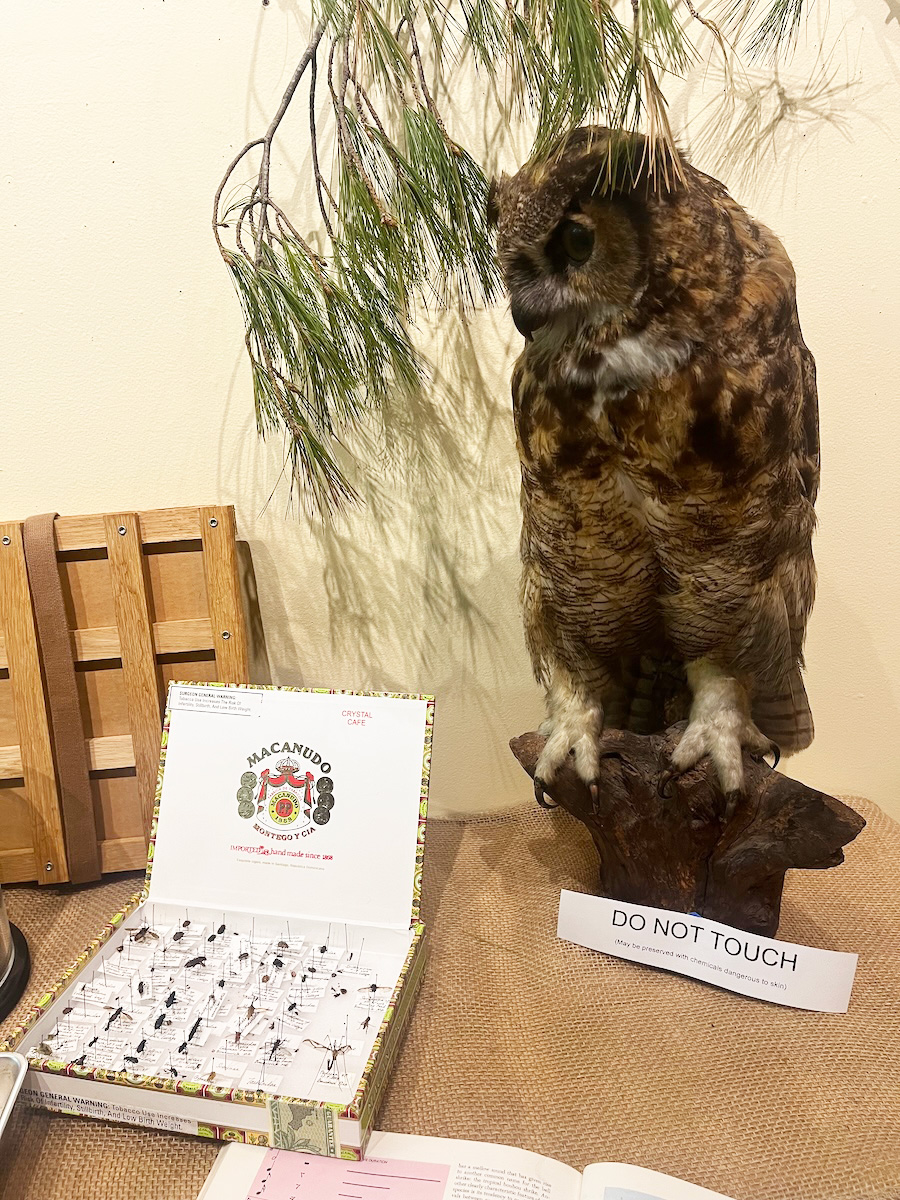

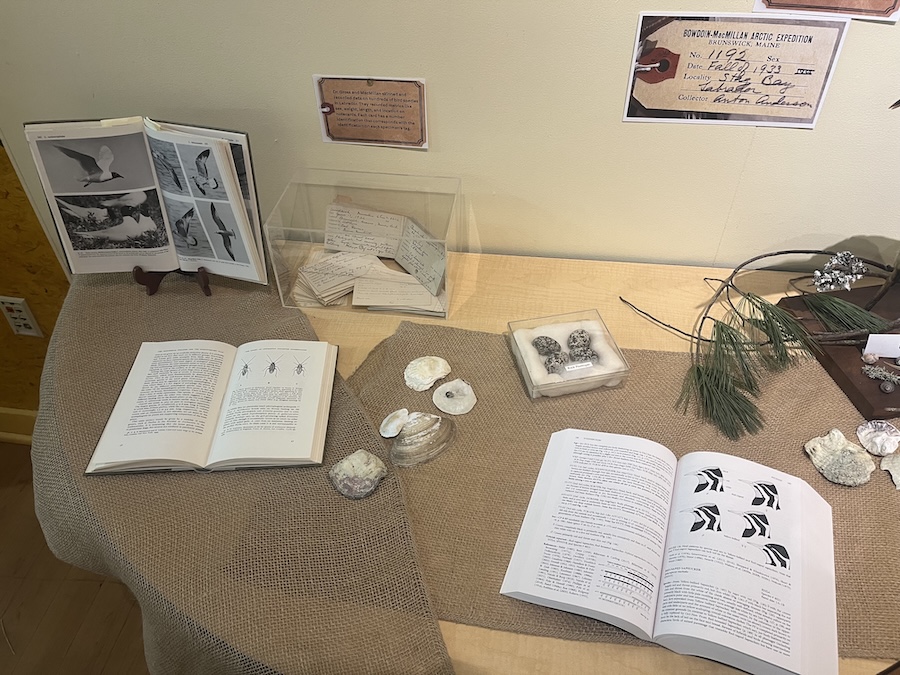

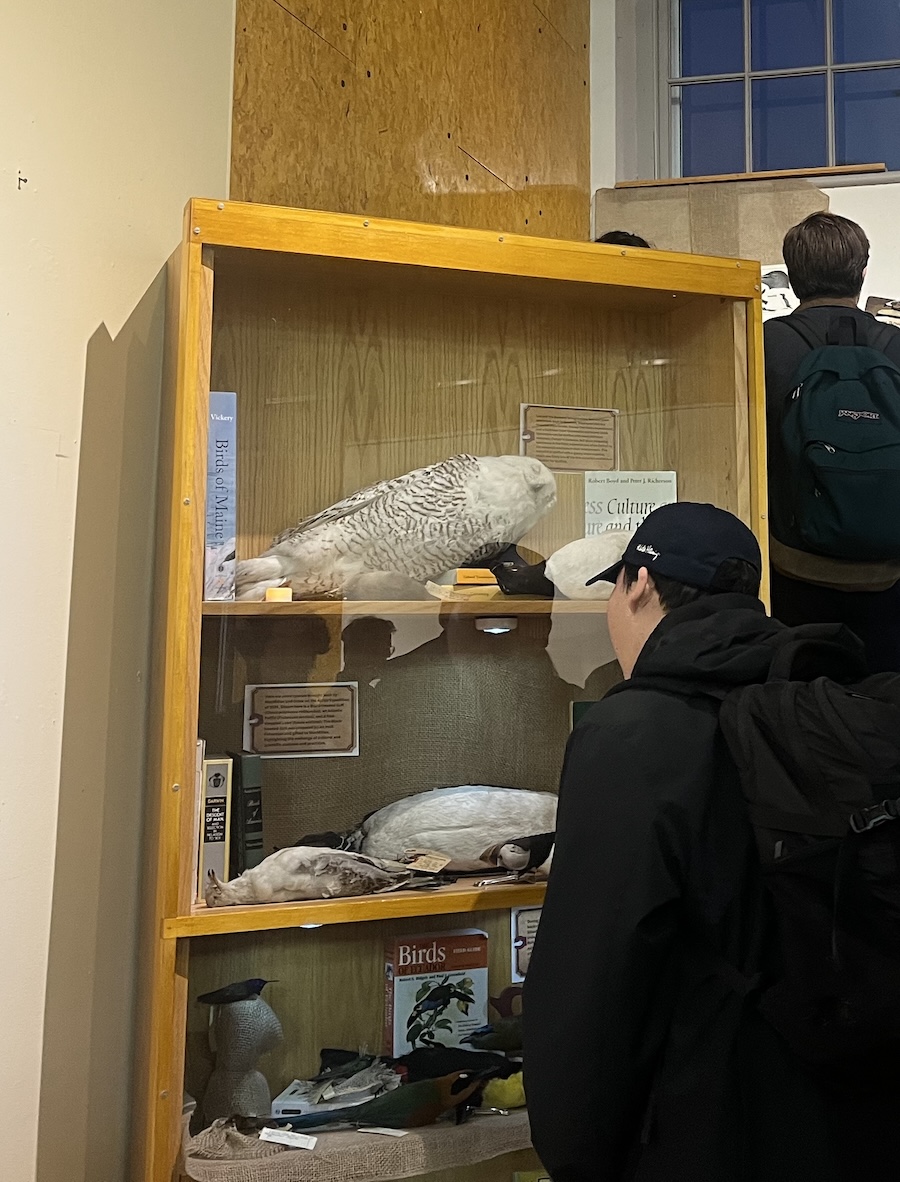

A stuffed owl and pinned insects in Lena Souffrant's “Dead Bird Stories.” Her recent exhibition was the culmination of two independent studies and was on view in Lamarche Gallery from May 5 to May 10.

Though Souffrant grew up loving natural history exhibits, she didn't initially set out to create her own version of them. Her original pitch to her advisor last year was to write a series of academic essays exploring the decolonization of museum collections.

But in the end, she decided to be both more ambitious and to focus more locally. Her end-of-semester show—in Smith Union's Lamarche Gallery from May 5-10—tackled the cultural, historical, and scientific forces behind the collection of avian specimens by Bowdoin researchers over the past 200 years. “I wanted to work with the birds themselves and I wanted to make some larger statements about why we have this collection at all,” she said.

When she offered up the idea to her advisor, Associate Professor of Environmental Studies and History Matthew Klingle, he enthusiastically agreed to advise her research on the exhibition's historical and cultural themes.

Liam Taylor ’17, Bowdoin's Doherty Kent Island Postdoctoral Scholar in Biology, served as her scientific advisor, teaching her how to catalog, organize, and care for the specimens, as well as helping form the final exhibition.

With guidance from her advisors, Souffrant embarked on new scholarly terrain. “None of us had really done anything like this before, but I appreciate Professor Klingle and Professor Taylor for jumping into this with me, and being creative and figuring out what worked,” she said.

In her invitation to the show, Souffrant wrote, “You are cordially invited to ‘Dead Bird Stories,’ a student-designed exhibition that challenges the entangled histories of science, colonialism, and ecological ‘discovery’ at Bowdoin College.”

The show examines the records of global travel by Bowdoin professors and students through the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. These intrepid teams would often return with once-live animals and other items collected from the places they journeyed through—all in the name of science.

“This exhibition invites visitors to reconsider the deeper legacies behind scientific collection,” Souffrant writes in her introduction to the show. “Bowdoin’s own history of scientific collection is a two-sided narrative: a public story celebrating daring feats, scientific achievements, and encounters with unfamiliar peoples and places.”

It is also, she added, “a shadowy story of cultural exploitation, economic extraction, and racial privilege. ‘Dead Bird Stories’ encourages reflection on how scientific knowledge at Bowdoin and beyond is created, who it serves, and who it silences.”

Souffrant, Klingle, and Taylor took on the role of detectives as they attempted to reveal the stories behind the long-dead birds. “It was really a series of hunches,” Klingle said, starting by looking at their tags and noting where they were collected”—from the shores of the Canadian and Greenlandic Arctic to the banana plantations of Costa Rica.

“And then assuming, rightly, that the names on the tags were not the names of the people who actually went out and shot the birds, prepared the birds, and collected the birds,” he continued. “In short, there were these hidden systems of labor.”

Souffrant noted that she learned a lot from her hands-on research, but was particularly fascinated by how intertwined natural history and the College have been over the centuries.

Through her independent studies over the past year, she unearthed a dusty historical detail about Bowdoin: the College used to have a natural history museum of its own. She hopes that her exhibit has helped to shed light on the many specimens Bowdoin has access to and how these specimens could be used educationally across the curriculum—in history, Africana studies, Latin American, Caribbean, and Latinx Studies, sociology, English, the visual arts, and other fields.

“These collections can and should be used not only for teaching biology, environmental studies, and earth and oceanographic science, but also for teaching in other disciplines across campus,” Souffrant said. “The stories of the birds fit perfectly into Bowdoin's liberal arts teaching philosophy.”

Klingle echoed her idea about the broad lessons conveyed by ‘Dead Birds.’ “Something like this is a testament to the power of the liberal arts, to be able to look at something from different perspectives and to acknowledge how those different perspectives open up new vistas for understanding,” he said.

In May, Souffrant will graduate from Bowdoin, and in August, she will matriculate at Yale in a masters degree program for environmental management.