Literary World Buzzes Over New Book by Professor Nadia Celis

By Rebecca Goldfine

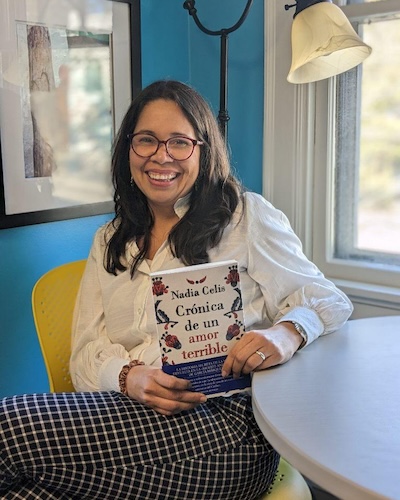

Nadia Celis with her book, Chronicle of a Terrible Love: The Secret Story of the Dishonored Bride in García Márquez’ “Death Foretold.” Celis is a jointly appointed professor in the Departments of Romance Languages and Literatures and Latin American, Caribbean, and Latinx Studies.

Television, radio, and print media—including Semana, El Espectador, Las dos orillas, El Universal (Colombia), Repeating Islands, El Heraldo, and El Tiempo—have featured reviews and articles about her book, with some even reprinting entire chapters.

Celis herself has embarked on an extensive book tour, giving talks at bookstores, book festivals, and universities in Colombia, Argentina, Mexico, Spain, and the US. Her Bowdoin colleague Carmen Greenlee, the College's humanities and media librarian, described the reception given to her as similar to a "rock star."

Celis's book, Chronicle of a Terrible Love: The Secret Story of the Dishonored Bride in García Márquez’ “Death Foretold,” published last spring by Lumen (an imprint of Penguin/Random House), is in part causing a sensation because it unsettles longstanding notions about a famous book by one of the world's most beloved novelists.

It is also a captivating personal narrative. Celis wrote Chronicle of a Terrible Love in the first person to to describe her investigation into a real woman, Margarita Chica Salas, who inspired the main character in Chronicle of a Death Foretold. In the process, Celis examines the flow between fiction and reality, looking not just at how real life influences storytelling, but at how stories shape reality.

At a recent book talk at Bowdoin, Professor of Romance Languages and Literatures Elena Cueto Asín said that Celis's narrative approach—unusual for an academic—directs the reader's attention to Margarita and to the impact the novel and the coverage of the novel has had on her. What follows is "a deep reflection on romantic love as a discourse that is perpetuated and accepted—yet is also destructive for females."

Cueto Asín also noted that "the real protagonist of the book" is not Salas but rather Celis, who by writing so intimately invites the reader to follow along in her detective work. "In a way Nadia make us all investigate, research, and engage in her yearslong work," she said.

The Real Protagonist

As a teenager in Cartagena, Colombia, Celis devoured García Márquez novels. She jokes that long before she fell in love with any man, she fell for the obsessive Florentino Ariza in Márquez's beloved novel, Love in the Time of Cholera.

But, as she got older, she began to look more critically at the Nobel Prize-winning author. "I was very uncomfortable with García Márquez since growing up in the Caribbean," she said. "I could identify with his portrayal of my culture, but I also felt annoyed and offended by his portrayal of women."

She added, "it wasn't until I was in graduate school that I could start investigating why." She earned her PhD in Spanish with a certificate in gender and women's studies at Rutgers University.

In 2016, Celis decided she wanted to do an in-depth examination of García Márquez’s female characters, curious about what her research might reveal about the intermingling of love, power, and violence in his works. At that point, she still planned to write a traditional academic book.

During her research, however, she made a startling discovery that upended her plans. While delving in the García Márquez archives at the Harry Ransom Center in Austin, Texas, Celis flipped through an early copy of Chronicle of a Death Foretold. The old manuscript contained an epilogue that had been removed from the final version. In it, García Márquez suggests "that the love story in the original novel, and its happy ending, was a true story," Celis recounted.

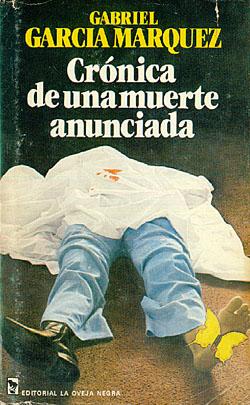

Chronicle of a Death Foretold, which was published in 1981, is based on a real murder that took place in a small town in Colombia in 1951. After a young bride (Margarita) is rejected on her wedding night when her husband discovers she is not a virgin, she accuses a man in her village of deflowering her. Her brothers then kill this man to avenge her honor.

"Many of his readers and critics knew that the book was based on a real crime," Celis said. “But everyone assumed that García Márquez had made up the rest of the story, the part about Margarita and the husband reuniting, very much in love, many years later.”

Celis was floored to read that this improbable romantic ending was real. "I already had an issue with this happy ending in the novel," she said, as it is a love that emerges from violence: the bride's rape by her husband and battering by her family members, and the brutal slaying of a man.

She said she began to be haunted by the woman at the heart of the tale, and suspected that she could not properly tell the story if she constrained herself to a scholarly voice. "I had to put myself in there to walk the reader through the process," Celis said. "Instead of explaining, I needed to show readers so they could put the pieces together and come to their own conclusions."

Fusing Fiction and Reality

To track down townspeople who knew Margarita, Celis returned to her home country, and the village of Sucre. "I went back to the town where the crime happened in the first place and witnessed firsthand the impact of the story, and the way it was told, on the people in the town," she said.

Neither Margarita—who had become a well-regarded seamstress in the ensuing decades—or her relatives would speak with Celis. (Although it's possible some will change their minds now that they have read her book.) "I had to recreate her portrait through her clients," Celis said, mentioning that the embroidery on the book's cover is a reference to her skills. "She had made herself a name, and had a decent life despite everything that had happened to her," she added.

It wasn't just the publication of the novel that had resurfaced old wounds. When the book came out, a series of journal articles exposed the characters' true identities, and Margarita was thrust back into the story—this time on a global stage, not just in her small town. "For her family, it was a story of shame," Celis said. "Any time anyone decided to dig again into the real story, it was very bad for her."

In his manuscript, García Márquez said that he was compelled to tell the story when he found out that Margarita and the husband had reunited. At that moment, “he realized that what he had thought was the story of a horrendous crime was actually the secret story of a terrible love," Celis said. This is also the origin of her book’s title.

Though García Márquez has said he wanted his novel to implicate an entire town in the bloodshed, he ended up emphasizing an unfortunate angle of the story, according to Celis. His version leans into the idea that the bride lies about to whom she had lost her virginity, and by so doing, condemns a young man to death.

"Everyone in town will tell you she was lying, because the story in the book became so embedded in everyone’s memory that they can no longer distinguish fact from fiction," Celis said. "So in the novel, and in reality, she is the one everyone blames. You go back to the town, and go back to Colombia, everyone will tell you this is a story about a man unfairly killed because of a woman's lie."

"The story that lasts is the story that blames her. It is very easy for society to blame the woman," she added.

Violence and love

When Celis initially launched her research project in 2016, she had wanted to explore the role of love and violence in García Marquez's novels—the way either, or both, is deployed to subdue women and neutralize their "unruly desires." Indeed, the two come together very frequently; female characters "are educated into love by violence," Celis observed.

"Love," she continued, "is the ticket that guarantees that women will willingly accept the position as subordinate to men and to their desires. Love is the artifact in these patriarchal societies that guarantees that women will surrender their own autonomy and desires and will even feel ‘happy’ about this."

With this in mind, Celis was struck by the narrative arc of García Márquez's Chronicle of a Death Foretold, particularly its ending. Long after the main character's rejection by her wealthy husband-to-be and the murder of her alleged lover, she ends up happily coupled with the man. Despite being raped, shamed, and traumatized by him, “she realizes she is crazy in love with him and writes thousands of letters to make him come back to her, with the unopened letters under his arm," Celis said. The idea that such ending could be based on a true story was a possibility that she could not leave be without investigating.

Celis stresses that her motive is not to harshly judge or condemn García Márquez. "I think there is tremendous potential for society when we look at his books from a critical perspective, especially his portrayals of patriarchy," she explained. "There is a lot to question, and García Márquez’s work is an instrument, a tool, for me."

And her book has touched many readers, well beyond her expectations. "I have had a lot of readers coming to talk to me who are openly thankful, telling me in public, 'Thank you for writing this,'" and saying the book encouraged them to examine their own partnerships.

These reactions are compelling her to work on an extension of the book, a related podcast with audio producer Lisa Bartfai and Futuro Studios. She explains her desire to continue the project by recounting another interaction she had with a reader who told her, "I will never be able to read García Márquez again in the same way." To this, someone nearby said, "I will never be able to read again in the same way."

Celis continued, "That was the moment when it came to me that this is not just me telling a cool story that will sound good in a podcast, this is an opportunity to reeducate listeners to see violence where they used to see love."

"This is the kind of feminism I have been meaning to do my whole life."

In the coming months, audio producer Lisa Bartfai and Nadia Celis will be traveling to Colombia and elsewhere to record Celis's conversations with people touched by Margarita Chica Salas and García Márquez's novel about her life.

Bartfai said when she first heard Celis speak about her book project, she knew it had the potential to be a great spoken story. "It has everything we look for in a podcast," she said. "It has a fantastic narrator, a personal connection, global relevance. It has that true crime that a lot of podcast listeners look for, and also a passionate love story."

The two are partnering with Futuro Studios to help finance and distribute the podcast, which should be available by the end of 2024. The podcast will be bilingual—with two versions recorded in Spanish and English.

"[The podcast] will be an extension of the research that led to the book in a number of ways," Celis said. "Some of it is going back to the people who gave their testimony in the first place and some who did not but who have become aware of the project because of the publication of the book."

Additionally, she is looking forward to more deeply exploring themes touched on in the book, "themes like the relationship of love and violence, the sentimental education of women in Latin America and the Latinx community,” but also new insights, such as “the perspective of a migrant woman who is doing research from the US about the Caribbean."

"And," she went on, "the recalibration of my relationship with one of my favorite authors through the lens of the investigator, the feminist researcher, the woman who grows up in tension with her own culture and goes back to it at different times in life, every time with different lenses."