Circumcision: A Changing Rite of Passage for Turkish Males

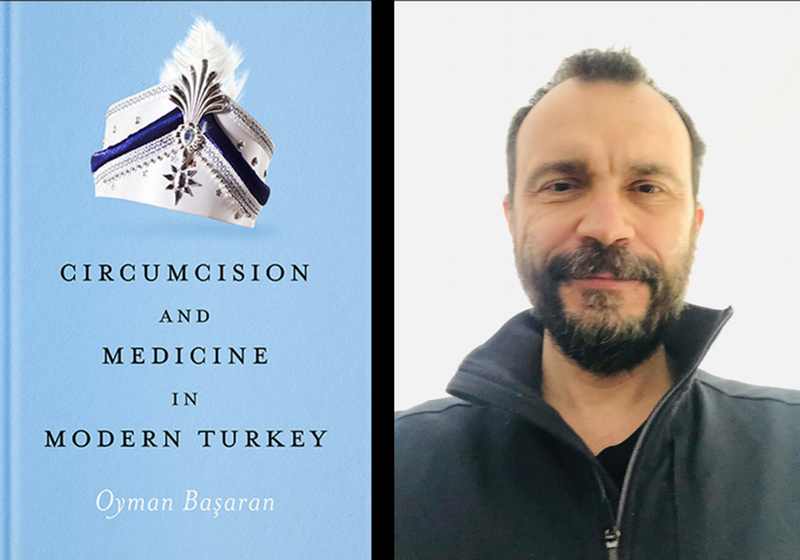

By Tom PorterAssociate Professor of Sociology Oyman Basaran is fascinated by the concepts of masculinity and gender in his native Turkey.

In earlier research, he explored this theme in the context of the compulsory military service that men are required to do in that country. For his latest project, Basaran examines another rite of passage familiar to Turkish males, circumcision.

His book, Circumcision and Medicine in Modern Turkey (University of Texas Press, 2023), looks at how a widespread religious ritual became increasingly medicalized, drawing partly on the author’s own experiences.

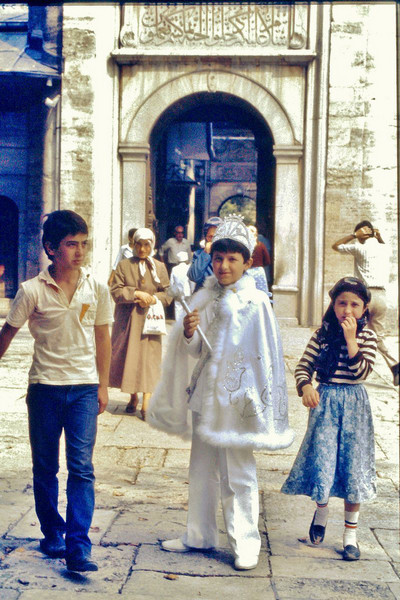

At a recent book launch event at the Bowdoin College Library, Basaran recalled the stress he went through as an eight-year-old boy taking part in a traditional mass circumcision event—a ritual characterized by gatherings, gifts, and special outfits. “The pain management had gotten OK by then, but not so much the fear management.” On several occasions, he said, the terrified boy would have to be held down by adults while the ritual was performed.

The tradition of circumcision goes back centuries in Muslim-majority Turkey, where the Ottoman Empire established the practice as a key socioreligious milestone in a young male’s life as he begins to contemplate manhood.

“Although there is no mention of circumcision in the Koran, it was still regarded as a religious obligation,” said Basaran, “Islam being a religion of cleanliness.” Furthermore, the ceremony has typically been held when the child is between the ages of six and ten, he explained. “This is so the child is aware of what is happening and remembers it as a story he can swap with friends later in life, in much the same way as Turkish males bond over the shared experience of military service.” This trend, however, is starting to change, he added, particularly among more secular families who choose to have their child circumcised soon after he is born.

Basaran’s book traces what happened when this longstanding practice came up against the demands of Turkey’s evolving and improving (albeit unevenly) health care system, and what this meant for the practitioners of the procedure. The practice had traditionally been done by itinerant circumcisers, often using herbal treatments on their patients, he said. This began to change in the 1960s, when public health officers increasingly assumed the circumcision role, as the practice became more systematic and professionalized with a greater emphasis on pharmaceutical pain management, explained Basaran. The situation had evolved further by the 1990s, he added, with hospital doctors also taking on the role.

Circumcision and Medicine in Modern Turkey closely examines the experiences of twenty-five cities and their outlying towns across Turkey. By analyzing the changing characteristics of the medical actors, Başaran offers an alternate approach to the study of what is a central part of the Turkish male experience.