A Journey through Environmental Studies in Art and the Archives

By Rebecca GoldfineAt the urging of a committed group of faculty and staff, Bowdoin founded its Environmental Studies (ES) program in 1972. To commemorate the occasion, the ES program organized a number of events this year, including the two exhibitions currently on display.

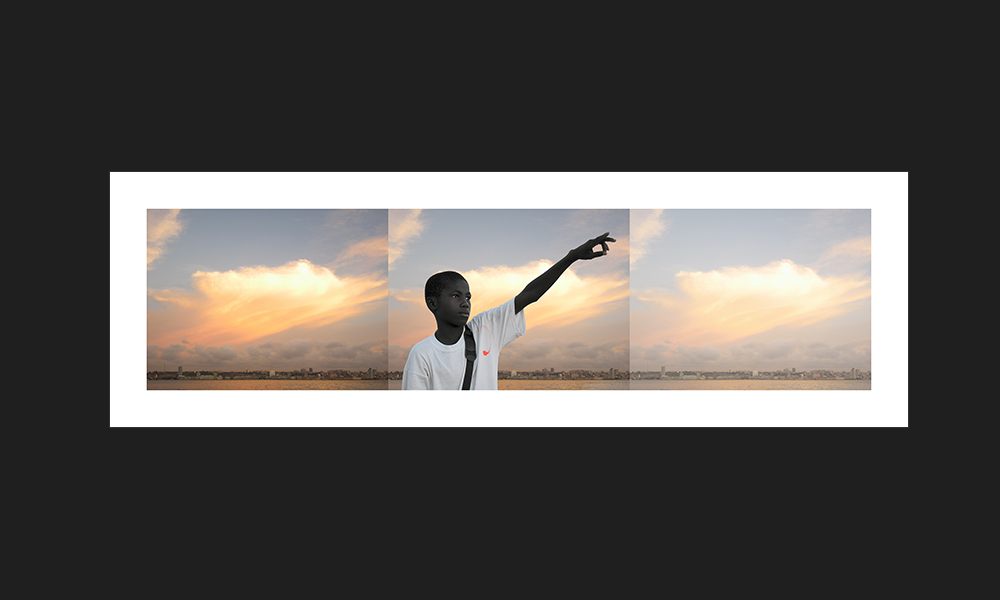

Human Nature: Environmental Studies at 50, at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art, explores connections between art and environmental studies in the twentieth- and twenty-first centuries.

Woods, Water, World: Environmental Studies at Bowdoin College, in Hawthorne-Longfellow Library, tells some of the key moment from the history of Bowdoin's Environmental Studies program.

Art and Environmental Studies

Last year, Associate Professor of History and Environmental Studies Matthew Klingle asked five students—John Auer ’23, Tess Davis ’24, Sophia Hirst ’24, Hayden Keene ’22, and Brandon Lozano ’24—whether they would be interested in collaborating on a special art exhibit to coincide with ES's fiftieth anniversary. All five eagerly accepted his offer.

"I taught these five students previously," Klingle said at a recent talk at the Museum during which he and four of the student curators spoke. "I asked them to join a class with no syllabus, no idea what I would teach, just that we would create an exhibition. I basically said, 'You have to have faith, we're going to build a canoe and learn how to paddle while we're building it.' And they jumped right in."

"We met weekly," Davis said, Zooming in remotely from her study-abroad program in Milan. "It was really wonderful—our conversations were filled with lively discussion and discovery."

The group began their independent study by considering two broad questions: "What can art teach us about environmental studies? And what can environmental studies teach us about art?" Keene said.

In their first meeting, they covered a whiteboard with possible themes for the show. In the end, they whittled the deluge of ideas down to three main concepts: bodies in nature, capitalism and consumerism, and the sublime.

In his review of the Museum's In Light of Rome: Early Photographs in the Capital of the Art World, Boston Globe critic Mark Feeney calls attention to the nearby show Human Nature.

"Different as Human Nature is from In Light—different in size, theme, appearance, form, locus, you name it—at least two images chime with the larger show," he writes, describing Pudlo Pudlat and Qabaroak Qatsiya's "striking" print and Richard Misrach’s "ravising" photograph “Diving Board (Salton Sea).”

In addition to those three, several more minor themes emerged over the course of their research, including migration, technology, gender, and spirituality—the last two often coupled.

After agreeing on the show's conceptual framework, their next step was to explore the College's major collections—in Special Collections, the Museum of Art, and the Arctic Museum—to hunt for pieces they thought reflected their themes. When they found a piece they believed belonged in the exhibition, they presented a case for its inclusion to the others.

"We wanted the themes to blend together and cohere," Hirst said. "When we presented possible artworks to the group, we talked about why we selected them, why we liked them, and how they fit one or more of the themes."

What emerged in the process were the environmental narratives they wanted to highlight, as well as ones they decided were no longer relevant, Auer said.

"If you think about nature in art, certain kinds of images come to mind, especially in the Hudson River School movement, where nature is sublime and people are rarely included. Or if they are included, they're very small in the corner of the canvas," Auer said.

Those images reinforce the notion that "people are separate from nature and nature is supposed to inspire awe," he added. "We wanted to challenge the idea, so we discussed how we could center people and the human experience in the conception of nature through art."

Additionally, they explored what they thought was missing from the canon of environmental art, Lozano said.

"We all tend to think about doom and climate change and other terrible things that will happen, but it is not the most productive way to represent the environment and have conversations about it," he continued. "So we identified issues that are equally as pressing as climate change," such as the representations of the human body in nature that emphasize the connections between humans and environment rather than our separateness.

Capitalism and consumerism only reinforce this close relationship. "We began to look at labor, and how it is important to understand that the environment we have today is the result of human labor and the effects of capitalism," Lozano said. "It raises questions about the systems we live in, the hidden systems, that define our environment and determine our future."

Though they moved away from outmoded notions of our natural world, Keene argued that a sense of nature's grandeur and mystery is still part of how people experience nature. "It was time to interrogate these old and outdated depictions of the environment as sublime, but I thought it was really important to keep the threads of awe, wonder, and divinity in our show—how humans feel in the vastness of nature. These are resilient themes."

"Art can teach us how everyday moments and ordinary moments can depict the transcendental elements of the human experience," she continued, "and how we can find the spiritual and sublime in the material and mundane, and in places that might be damaged." And this perspective is a tool, she suggested, that can help us weather the climate crisis and all that the future holds.

Human Nature: Environmental Studies at 50 is currently on view in the Bowdoin College Museum of Art's Becker Gallery through June 4.

Archives and Environmental Studies

Last summer, Lizzy Kaplan ’23 was hired to dig through the George J. Mitchell Special Collections & Archives and uncover the history of environmental studies at Bowdoin.

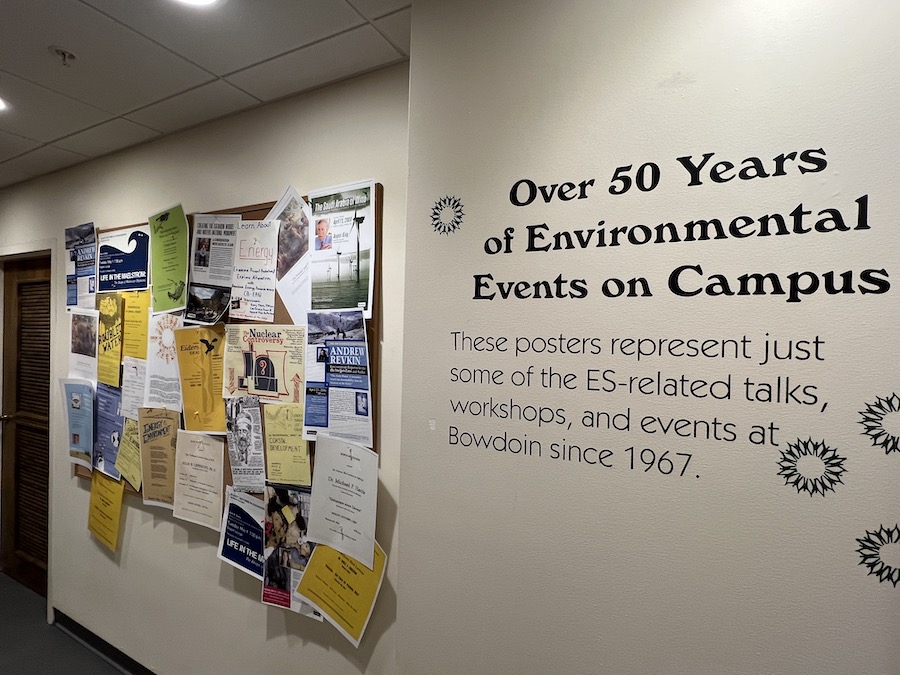

Kaplan's goal was to create an exhibit that would complement the ES program's 50th Anniversary Symposium on April 13-14. The result—Woods, Water, World: Environmental Studies at Bowdoin College—is on display on the second floor of Hawthorne-Longfellow Library through June.

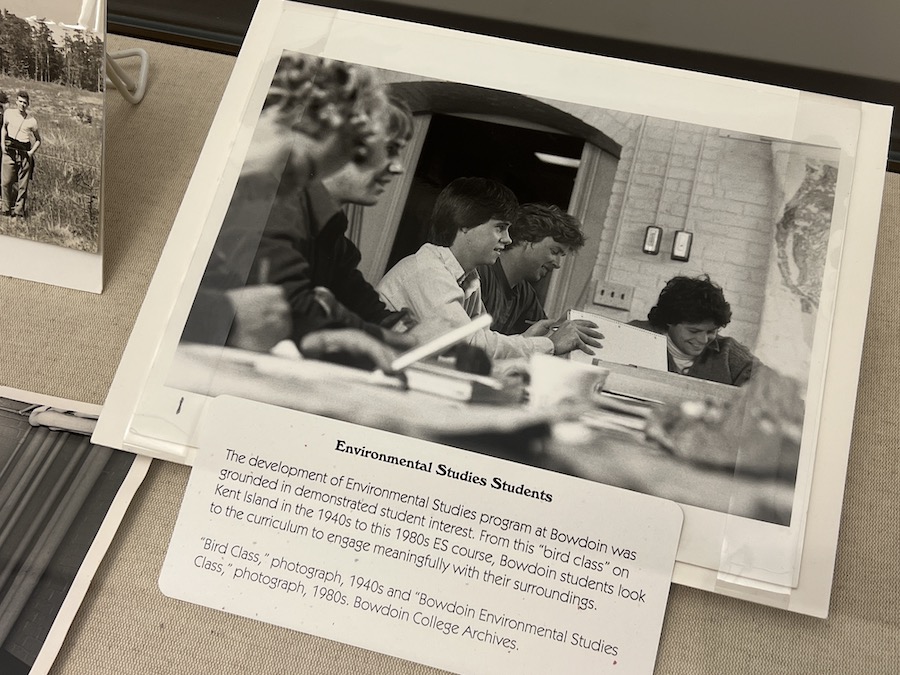

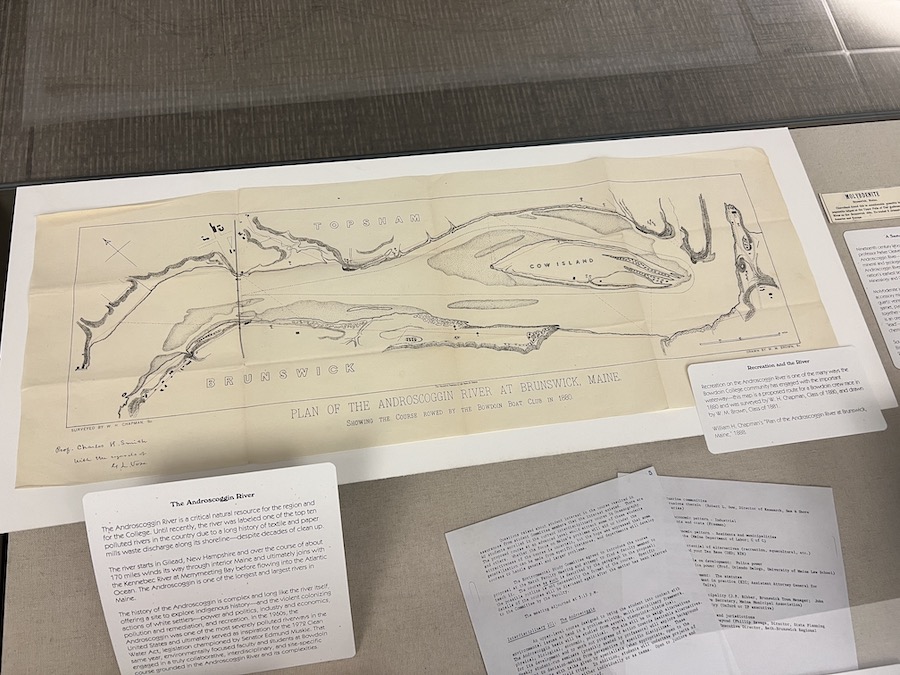

Kaplan, an economics and environmental studies major, spent many quiet hours in the reading room of special collections, leafing through documents, poring over photographs and sketches, examining old posters and pamphlets, and beginning to piece together a complex story.

"All the narratives that she pulled out of the archives do an incredible job at telling a really big story," said Marieke Van Der Steenhoven, Bowdoin's special collections education and engagement librarian. "Lizzy made some beautiful choices in terms of putting together the story of the environment, Bowdoin College, and the development of this academic discipline."

The exhibit includes eight display cases, each one covering a different aspect of the College's environmental history. "This commemorates fifty years of environmental studies at Bowdoin, but it is more than that," Kaplan said at a recent talk in the Library. "It is about the people, places, and things that make the program."

She recounted how she delighted in learning about Parker Cleaveland, who became Bowdoin's first professor of mathematics and natural philosophy in 1805. (He retired fifty-three years later.) "He was fascinated by the Maine environment, and made that part of Bowdoin's identity," she said.

Another figure she came to admire was a twelve-year-old girl and budding naturalist named Helen Johnson (1885-1957), whose father was a Bowdoin professor. In one of the cases, Kaplan includes a notebook of Johnson's in which the young girl catalogued fifty native trees species in Maine.

In another part of the exhibit, Kaplan sheds light on the story about the "key people who banded together to make environmental studies an academic program" at Bowdoin in the early 1970s. The group included an economist, a chemistry professor, two biologists, a geologist, and students.

"Students are the force behind creating programs and making change at the College," Kaplan said, before describing trends in what captured students' attention through the years. In the 1970s and 1980s, students were concerned about nuclear energy and oil. In the 2000s, they got invested in solar power.

Some themes, however, have remained constant over time. "The more biocentric events and interests, like birds and animals—it could be fifty years ago or today," she said.

Curated by Lizzy Kaplan ’23, with guidance from special collections staff, Woods, Water, World is on view through June 2023.