For the Sake of Honor: Katherine Bradford

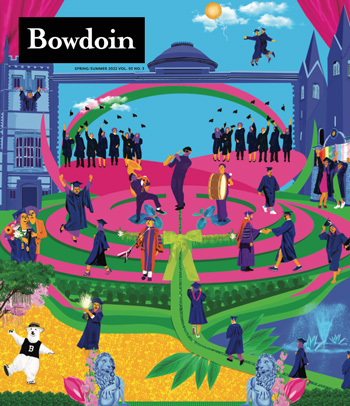

By Tasha Graff ’07 for Bowdoin MagazineOn May 28, for the first time in 217 Commencement Ceremonies, the College presented all of this year’s honorary degrees to women as part of its celebration of fifty years of women at the school.

Accomplished across all different fields, these five women inspire not only with their achievements but also with their graciousness, generosity of spirit, and grit. Accepting challenge after challenge, each called upon in her own way to find courage and determination, they all remained, as writer Kenny Moore once put it, “unharmed by victory.”

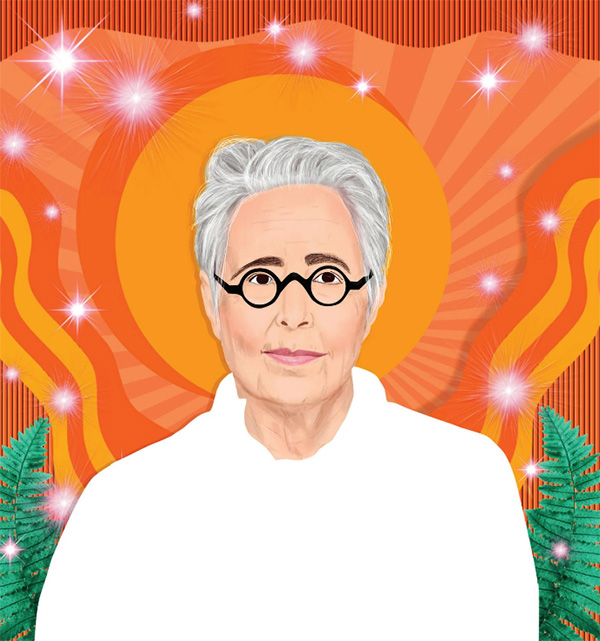

Katherine Bradford

Katherine Bradford upended her world to live and work as the artist she wanted to be, making paintings filled with feeling.

Katherine Bradford’s paintings are full of color and emotion. Androgynous and often faceless subjects swim, dive, dance, and embrace; they float in bodies of water and in outer space. Her singular style is as bold as it is unassuming, and her paintings are instantly recognizable.

Over the course of six decades, Bradford created a body of work that transformed her from a new painter who first began making art after moving to Brunswick, Maine, to one of the state’s most iconic and beloved contemporary artists. Her paintings are shown in galleries and museums across the world, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Institute for Contemporary Art in Boston. Approximately forty of her paintings will be on display at the Portland Museum of Art throughout the summer in the show Flying Woman: The Paintings of Katherine Bradford.

Bradford’s grandfather Jacques André Fouilhoux was a famous architect, a profession her brother also took up, but Bradford’s mother encouraged her daughter to follow a more traditional path: “I think she thought being an artist meant that you would lead a desolate life, and she wanted other things for me, like all mothers,” said Bradford.

Born in 1942 in New York City, Bradford grew up in Connecticut and left home in 1960 to attend Bryn Mawr, where she earned a BA in 1964. She married Peter Bradford soon thereafter and gave birth to twins in 1969. Her life became the traditional one her mother wanted for her: an educated wife and full-time mother. Something was missing, though Bradford had not quite figured out what. It wasn’t until the early seventies in Maine that she discovered a community of artists, and her world was upended.

The artists she met in Maine shaped her future: “The way they lived their lives and questioned the system appealed to me so much. It finally clicked with me that being an artist was a way of going through life, a whole world-view. I could relate to that.” By 1975, she had cofounded the Union of Maine Visual Artists and began reviewing art for The Maine Times.

Even so, life as an artist did not come easily. She broke from conventions of the time to pursue painting. “By the time I admitted to myself that I wanted to be not just an artist, but a good artist, nothing was in place. I was living in Maine, we had a woodstove and an organic garden, and it took me a long time to turn my life around and live as an artist—including getting divorced. The big thing was that the grandmothers wanted me to be there raising the kids.”

Bradford moved to New York with her children despite her family’s disapproval. Asked what made her “take the leap” to become an artist, Bradford replied, “It wasn’t a leap. It was one step after another.”

In an interview with her son Arthur years later, Bradford explains how the move impacted the twins: “When we moved to New York, you both were distraught, but in time each of you in your own way thanked me for introducing you to city life. I needed New York. The language of painting is spoken so fluently and so beautifully there.”

Katherine Bradford, Mother Ship, 2006, oil on canvas, 30 x 24 inches.

Collection of William Finn and Arthur Salvador © Katherine Bradford.

Image courtesy Stephen Petegorsky Photography.

Bradford began generating a tremendous amount of work. In 1987, she graduated from SUNY–Purchase with an MFA. She began to exhibit in galleries and, slowly but surely, began to attract attention and recognition in the art world.

In the beginning, Bradford had thought of herself as a maker of marks, an abstract painter. But she began to see forms in her work even as she did so. “Because the surface was made using many thin layers of paint,” she said, “small shapes and glints of light would appear, sometimes suggesting something underwater.” After a while, she realized maybe she wasn’t an abstract painter after all, that the fields of color could lead to landscapes and expanses of ocean.

In an interview with The Brooklyn Rail in 2007, Bradford said, “If you want to ask me point-blank why I stopped being an abstract painter and reintroduced images into my work, I can tell you. It was because I wanted more emotion and I wanted to tell stories.” In 2010, Bradford received a Guggenheim Fellowship, and a year later she received a grant from the Joan Mitchell Foundation. She has also received awards from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, grants from the Pollock-Krasner Foundation, and the Rappaport Prize.

Bradford describes finding her voice in a 2017 interview with New American Paintings: “I think [we artists are] trying to speak a language, a visual language, and it takes a long time to develop a very personal vocabulary. It certainly took me years and years to find my own voice. And I wouldn’t say it has anything to do with age; it had to do with sticking to it, and doing it a lot, like an athlete.”

She works on paintings in her studio, where they are surrounded by all her other paintings, and she has said that “the characters I work with, like divers and soaring superheroes, travel to neighboring paintings in my mind,” creating worlds where swimmers float along in outer space or figures in capes soar above the sea.

Admitting that it’s expensive to have so many unfinished paintings around, she says, “Sometimes I line them up here and take a brush, like a doctor visiting a ward, and I try to save the ones that are dying.”

But none ever seem to be dying. Artist Anna Kunz describes Bradford’s work as being “akin to poetry in its attempt to turn fleeting emotions into something concrete and thinkable,” and said, “More than anything, I like Bradford’s paintings because they are so unequivocally what they are: unpretentious and joyful, at times discomfiting, and at times just plain funny.”

Bradford works to create community with her audience.“I have two paintings which are somewhat about identity,” Bradford said. “They’re figures with choices of different heads. I’m exploring who we are, how we fit in, how we fit in together visually, how we all stand next to each other, and there are quite a lot of options for how to look and be with one another.”

Riders of the New York City subway can view Bradford’s work in an unlikely spot: the L train station at the intersection of First Avenue and East 14th Street. Commissioned by the MTA and unveiled in September 2021, the permanent installation consists of five glass mosaic murals depicting her whimsical characters. There are superheroes, a man in a ball gown in a garden of white flowers, and figures dancing across an expanse of blue. Two at the entrances can be glimpsed from the street. Bradford said at their unveiling, “Once someone steps into the subway area, we become travelers, and my hope is that these artworks will transport you to another place.”

Her most recent exhibition, Mother Paintings—which collects works that Bradford created during the pandemic, when she said she was thinking of comfort and caregiving—has been called “a heartfelt meditation on raising other beings—children, paintings—and being raised oneself,” by critic Jason Patrick Brooks, who went on to say: “Bradford also grapples with her own legacy and with the legacies of her predecessors, be they relatives or fellow artists, asking vital questions about what it means to be remembered and to leave a mark.”

In her eighties, Bradford is still painting, still giving talks, still hosting studio visits. She and her spouse, Jane O’Wyatt, whom she met in 1990, split their time between New York and their home in Maine.

“Now I’m surrounded by an entire community of artists, and not too many of them had to fight as hard as I did to become an artist. And in a way, I think it’s why I’ve stuck with it. When I wake up in the morning, I’m not going to fool around, I’m going to get to the studio.”

NEXT: Raquel Jaramillo »

This story first appeared in the Spring/Summer ’22 issue of Bowdoin Magazine. Manage your subscription and see other stories from the magazine on the Bowdoin Magazine website.