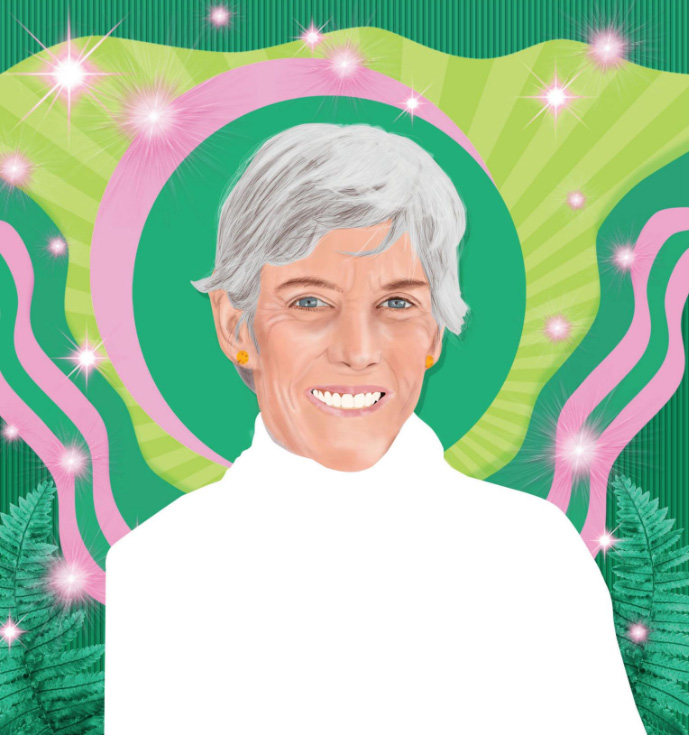

For the Sake of Honor: Joan Benoit Samuelson

By Tasha Graff ’07 for Bowdoin MagazineOn May 28, for the first time in 217 Commencement Ceremonies, the College presented all of this year’s honorary degrees to women as part of its celebration of fifty years of women at the school.

Accomplished across all different fields, these five women inspire not only with their achievements but also with their graciousness, generosity of spirit, and grit. Accepting challenge after challenge, each called upon in her own way to find courage and determination, they all remained, as writer Kenny Moore once put it, “unharmed by victory.”

Joan Benoit Samuelson

Joan Benoit Samuelson is the rare athlete who can dominate her sport, exemplify toughness, and be fiercely competitive—all while being “unharmed by victory.”

Maine's coastline runs for about 228 miles, and when you include all the nooks and crannies of the iconic rocky shore, the mileage swells to 3,748. Whichever measurement you choose, neither comes close to the estimated 150,000 miles (and counting) that Joan Benoit Samuelson ’79, P’12 has run in her lifetime.

To put such a number into perspective, if you laced up your sneakers in Samuelson’s hometown of Cape Elizabeth, jogged the 240 miles east to catch the first sunrise in the nation in Lubec, ran northwest for 260 miles to reach Maine’s northernmost village of Estcourt Station, circumnavigated the globe six times, and then ran three marathons, you’d almost reach Samuelson’s lifetime running mileage. Somewhere in the middle of that you would have worn out your running shoes about 300 times. All those miles led to medals, shattered records, and honors over her astounding career, from standout high school and collegiate athlete to Olympian, from elite world-class runner paving the way for the future of women’s athletics to serving as inspiration for generations of runners.

“Runners talk about Joan with a different tone of voice,” said a fellow racer. “She represents the ultimate athlete—someone who has been able to push herself to the limit.”

Samuelson began running in high school, but her first love was skiing. “I had aspirations of making it to the Olympics or into a world championship as a ski racer. My dad [André Benoit ’43] brought us up on skis, my brothers and me, about the same time that we were learning how to walk. He had a real passion for skiing and had served in the 10th Mountain Division during the war. And he wanted his kids learning how to ski as early as possible. That was one of the few sports that I could do as a young girl.”

In tenth grade, Samuelson broke her leg skiing on Pleasant Mountain. During her rehabilitation, her doctor recommended running to strengthen her leg muscles. The perseverance and stamina she harnessed at sixteen would become hallmarks of her career. It helped that she happened to find running “easy and fun.”

She soon became the only female runner on the Cape Elizabeth High School team. At the time, girls’ track teams weren’t given varsity status, and girls weren’t allowed to run for more than a mile. Samuelson was known to skip study hall in favor of running a four-and-a-half-mile loop around her school, and several boys recruited her for a race when another school arrived with female competitors.

Samuelson won her first road race, the Great Pumpkin Classic in Sacopee Valley, in 1973 at the age of sixteen, a year after Title IX had been signed into law, granting equal access to girls and women in athletics.

“Oftentimes, I think of myself as having been in the right place at the right time for many of my accomplishments,” Samuelson said when describing the doors that opened to her in high school after Title IX, a legislation that she describes as “transformative” and which she credits for her career as a runner and the opportunity to be an Olympian.

Samuelson matriculated at Bowdoin in the fall of 1975. There was no women’s track team at Bowdoin either at that time, so she spent a year at North Carolina State to focus on training. Samuelson, who has said, “I’ve never left Maine without wishing I didn’t have to,” came back to Brunswick to earn her diploma at Bowdoin.

In April 1979, still a student, she entered the Boston Marathon. She had run just one other marathon, which she happened to do in Bermuda in a fast enough time to qualify for Boston—and she was not only a relative unknown, she had never even seen the course. She had to park far away and run two miles just to get to Hopkinton, and she just made it in time for the start.

But, wearing a Bowdoin singlet—and endearing herself to Bostonians by adding a Red Sox cap for the last few miles—she won, beating the previous record by eight minutes. When she returned to campus, she received a standing ovation from her classmates in the dining hall. She remembers being moved by the applause and also surprised—running was something she did to challenge herself, not something she talked about or thought anyone much cared about.

Samuelson is no stranger to adversity. An emergency appendectomy kept her from running the Boston Marathon in 1980. In 1981, she had Achilles surgery that kept her from running for ten weeks, and she was diagnosed with asthma in 1991. But her most famous comeback was in 1984, just seventeen days after knee surgery, when she won the Olympic trials. Her coach, Bob Sevene, said at the time, “Her willpower is unreal. She’s the greatest athlete I’ve ever been around. The toughest I know. Her wheels will have to literally fall off to stop her now.”

She would go on to win the gold medal in the inaugural Olympic women’s marathon with a gutsy, risky performance. The executive director of the Women’s Sport Foundation said of her win, “She never slowed, she never faltered. She ran with a determination that from beginning to end never wavered. It closed the book on whether women were made of the right stuff in distance running.”

In 1984, she held the American record for four events: ten miles, the half marathon, the 10K, and the 25K. That was also the year she married Scott Samuelson ’80, whom she had met at Bowdoin her sophomore year. The Samuelsons live in Freeport, where they raised two children—a daughter, Abby, and a son, Anders (Class of 2012). “I think about the lack of opportunity I had before Title IX, and then the opportunities that I had, and then I look at the even greater slate of opportunities our daughter had, and I hope it’s even a bigger canvas for our granddaughter, whether it’s running, the arts, the sciences—whatever field it is that she wishes to pursue.”

She ran the Boston Marathon in 2014 with both her children, and, in 2019, she and Abby ran Boston together. Samuelson finished first in her age group, achieving a personal goal of finishing within forty minutes of her world record forty years after her first win; she wore another Bowdoin singlet for the occasion.

While perhaps best known for her own running feats, Samuelson has also worked to make running available for others. She founded the Beach to Beacon 10K road race in her hometown in 1997. When describing the race from the sidelines, Samuelson said, “I love watching the elites come in. But I also love watching the people in the very back come in, because they’re the ones that surprise themselves and find great pleasure in doing something that they never really thought they would do.”

This speaks to Samuelson’s passion: keeping pace, breaking her own records, and inspiring people around her in the process. She has spent her life giving back, sharing her passion, giving motivational speeches, and serving on boards ranging from the Friends of Casco Bay and the Freeport Recreation Committee to the board of trustees at Bowdoin.

With all her honors and accolades, Samuelson remains, as one journalist put it, “unharmed by victory.”

When she received the Bowdoin Prize, the College’s highest honor, in 1985, she said, “We all face challenges. We are all called upon to have courage. Those of us who survive and prosper from both success and defeat are the lucky ones, and I am very happy if my running proves to anyone else that whatever needs to be done can be done. But it makes me extremely uncomfortable to be given credit for the fact that someone else has found strength. No matter how you find it, it belongs to you.”

NEXT: Katherine Bradford »

This story first appeared in the Spring/Summer ’22 issue of Bowdoin Magazine. Manage your subscription and see other stories from the magazine on the Bowdoin Magazine website.