The Eighteenth Century “Wife Guys”

By Tom Porter“Wife guys”—men who are known for publicly celebrating their marital bliss on social media—are nothing new, writes Associate Professor of History Meghan Roberts in Slate. Eighteenth-century France was full of them, she says.

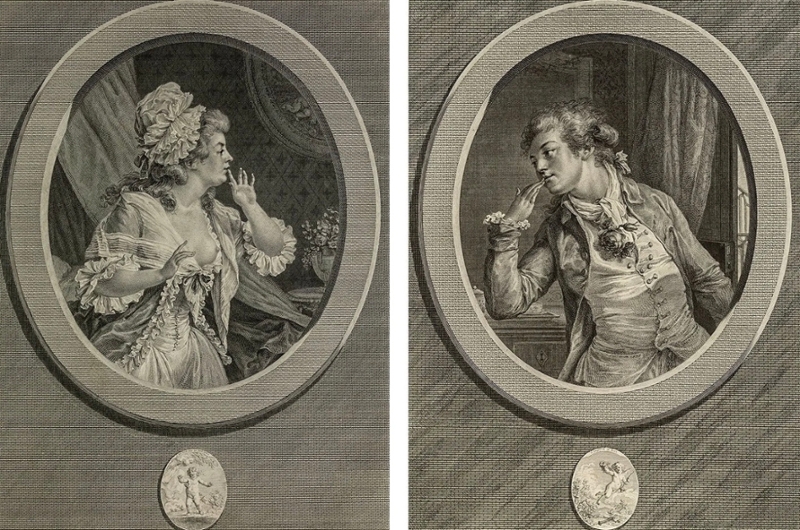

“Enlightenment ‘wife guys’ didn’t have social media, and the world’s first photograph was still decades away,” says Roberts. “But they did have portraits, and this is where eighteenth-century wife guys took center stage. They were not the first men to love their wives—of course not—but they developed new and very public ways to perform that love.” The late 1700s saw more and more portraits of married couples—rather than paintings of the whole family—and these were often the celebrity couples of their day.

Roberts says one of the most notable examples of such a work was Jacques-Louis David’s portrait of Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier and Marie-Anne Paulze Lavoisier. “Everyone involved in this portrait was a rock star in their own way: David was one of France’s most brilliant and sought-after painters, while the Lavoisiers were fabulously wealthy and famous for their work in chemistry. Like many ambitious men today, Lavoisier used his wife to improve his reputation—or, we might say, his brand,” she writes. Paulze Lavoisier, meanwhile, is described as “a famously charming host and her husband’s most significant collaborator: She wrote translations, sketched illustrations, and, most importantly, ran an extensive campaign to boost her husband’s research over that of his rivals.”

The development of this type of celebrity was made possible by a media revolution of the day, explains Roberts, due to “rising literacy rates, the birth of a slew of new newspapers, and lower prices for all kinds of media. Biographies and novels became huge bestsellers, encouraging readers to take a deep interest in the intimate lives of ordinary people—and, eventually, celebrities.” Although the technology was clearly different in the eighteenth century, says Roberts, “the basic culture of selfies and sprawling fandoms was alive and well.” Read the article in Slate.

Meghan Roberts is the author of Sentimental Savants: Philosophical Families in Enlightenment France (University of Chicago Press, 2016). This semester she is teaching The French Revolution (HIST 2060) and History of the Body (HIST 2543).