The Collective Creativity of the Black Lady Art Group

By Rebecca GoldfineThree students—Amie Sillah ’20, Amani Hite ’20, and Destiny Ariana Kearney ’21—formed the Black Lady Art Group in 2020 to pursue art in community with one another.

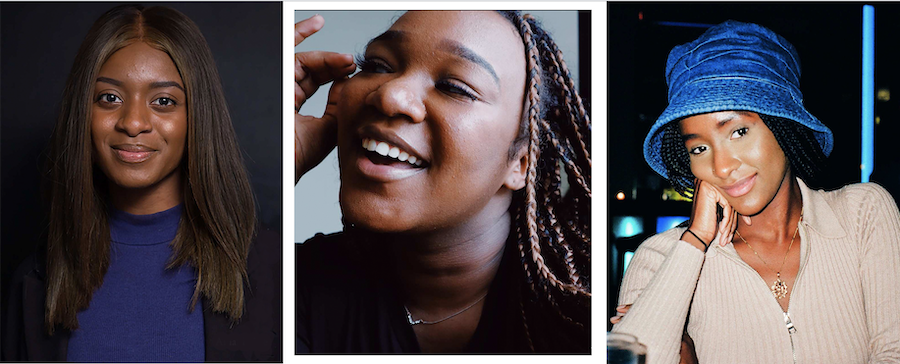

Amani Hite ’20, Destiny Kearney ’21, and Amie Sillah ’20. Hite was a visual arts major and gender, sexuality and women’s studies minor; Kearney was an African studies, art history and visual arts major; and Sillah majored in gender, sexuality, and women's studies and minored in sociology.

Their ultimate goal was to create a large-scale display of their art across campus—an unmissable, unmistakable reminder of three Black female artists doing something new at the College. "This was something Bowdoin had not seen before," Hite said.

This was ground they were breaking: They were in a self-designed seminar made up of Black students. They occupied a shared studio in the Edwards Center for Art and Dance. They had a Black arts collective, a group that supported and fostered artistic exploration And they were creating works to share with the College community that examined issues of identity, race, Blackness, and belonging at Bowdoin and beyond.

That the pandemic happened and they were forced to separate and leave campus did not deter them. They just altered their plans.

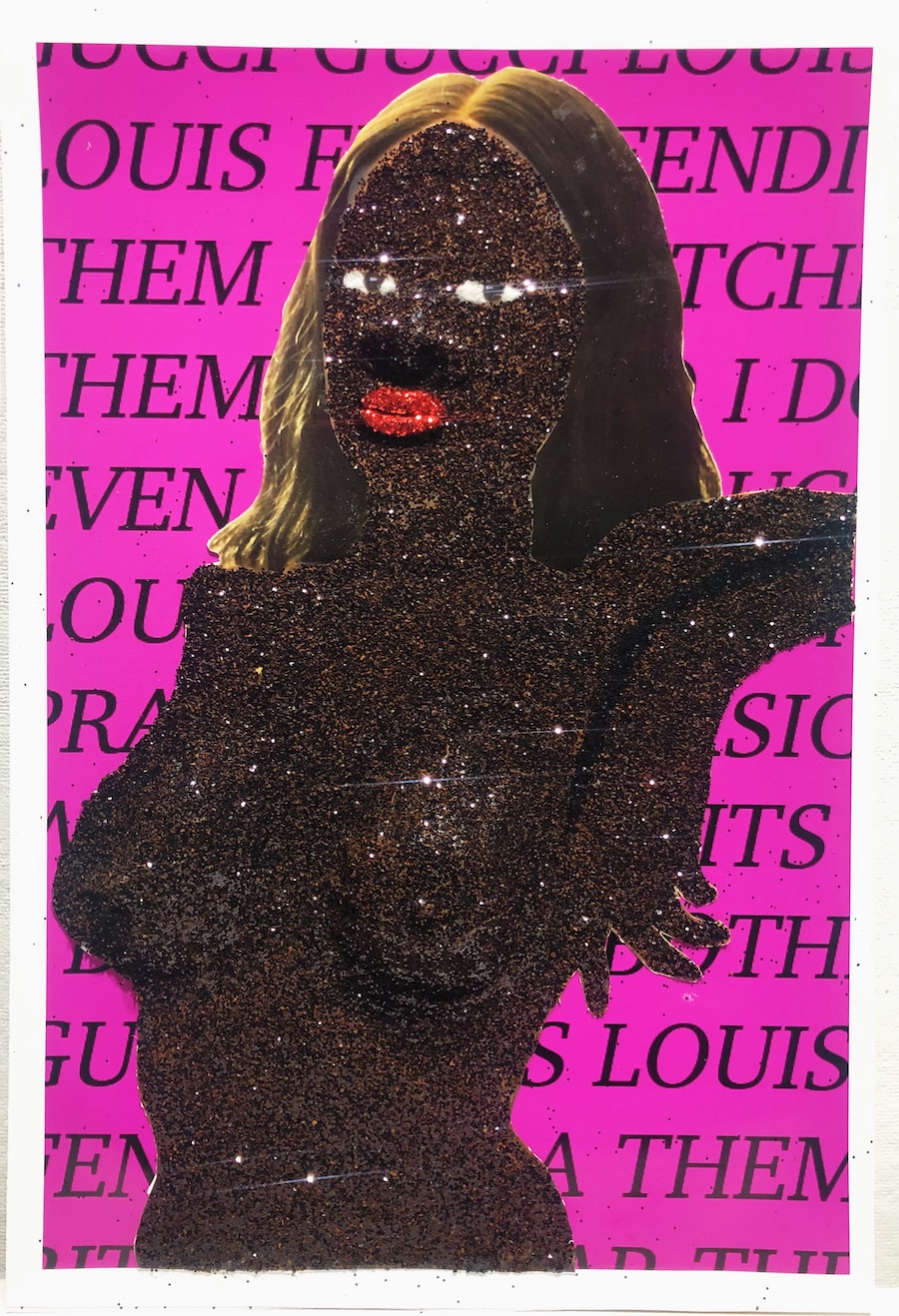

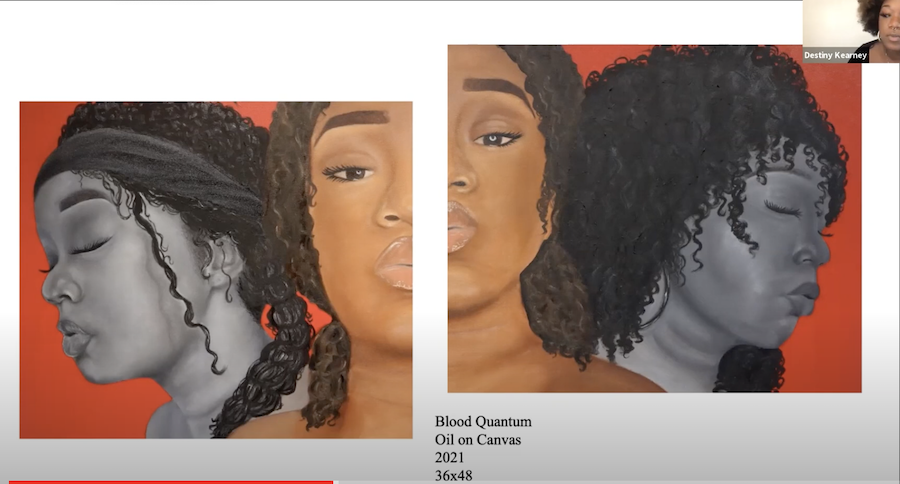

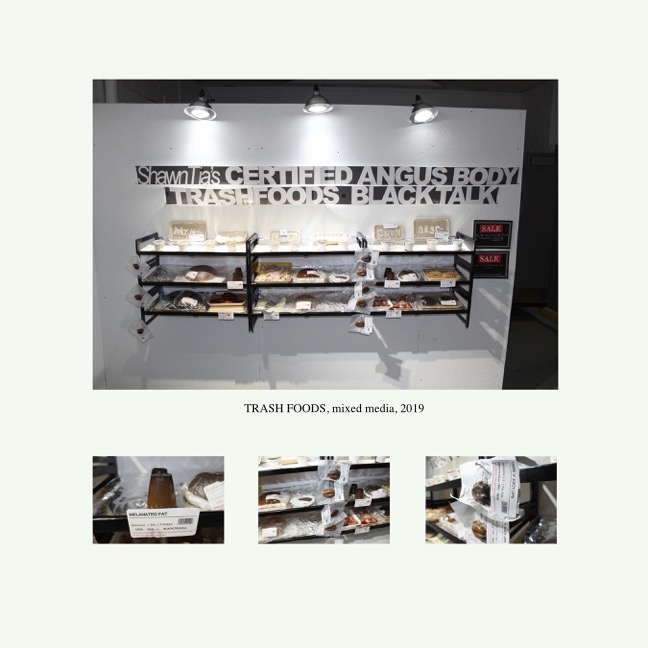

Below are a few examples of works by the artists that came out of the Black Lady Art Group.

Collectivism in action

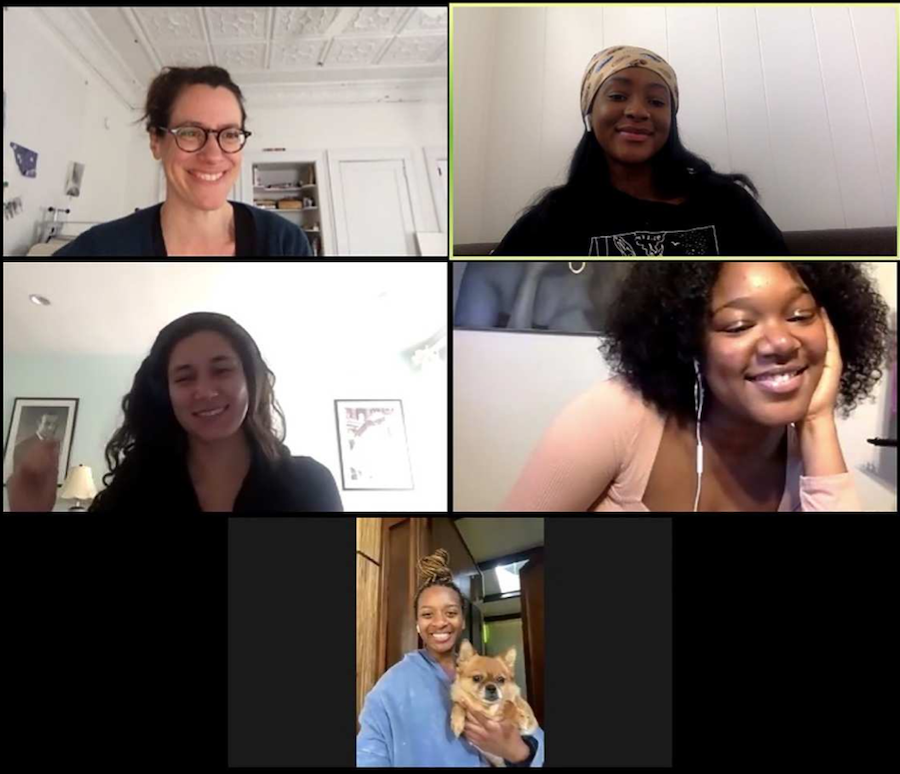

The three alumnae returned to Bowdoin via Zoom this fall to discuss the impact of the Black Lady Art Group on their final months at the College and on their current work.

Sillah was the one who first brought the group together. In her senior year, she invited Kearney and Hite to participate in an independent seminar of her own design, a class based on her Mellon Mays Undergraduate Fellowship research into the Black Artists Movement of the 1960s and 1970s.

She decided she wanted to experience for herself what it was like to work in a collective. "They trusted me," Sillah said. "Destiny and Amani trusted me, which I took very seriously and honored."

Her class, called In, Not Of..., was advised by Professor of Art Carrie Scanga and included a fourth senior who was to serve as a curator of their final show, Claudine Chartouni ’20.

Though art is often idealized as a solitary journey by an individual visionary, Sillah questioned this notion. "I work in community in so many ways outside of my art," in activism and academics, "so why couldn't I bring that into my practice?" Additionally, she noted, the Black experience in the US is not singular, so "Why should I suppose the artwork I produce is?"

To guide Sillah on the course structure, Scanga said she drew from her own experience as a young artist working at Women’s Studio Workshop, a nonprofit studio collective. "Finding space in Edwards was a challenge, because the building is already packed tightly, but we surmounted this problem because it was important for the artists to be able to make something physical in real space together," she said. "Many of the artist collectives I know of, including Women’s Studio Workshop, came about because of a need for shared physical studio space. Especially when you’re making something physical, space can be a signifier of power."

In their time together, the group studied Black female artists and read women theorists of color. They gathered twice a week for discussions and ongoing critiques of works-in-progress, and they worked day and night in their studio. They also regularly invited faculty from other departments—including gender, sexuality, and women's studies, English, and art history—to join their critiques.

Scanga hopes the Black Lady Art Group sets a precedent at the College. "I want to encourage more Bowdoin students in Visual Arts to shape the department to create the spaces they need to thrive," she said.

The class provided "a brief moment of feeling in the space," Sillah reflected. The two prepositions in and of refer to the course's overarching theme, which suggests some members of a community or institution can be admitted into its confines while still not being fully incorporated into its culture. "Having a class was a way of institutionalizing us. It was a way of putting our mark there in a way that was concrete and will live on after our time at Bowdoin," Sillah said.

Kearney said the class provided an opportunity to "create an intimate production space among Black women." That intimacy led to vulnerability, which led to art-making the three say they may not have undertaken if they had not been in the seminar.

"The collective was a turning point that changed everything for me," Kearney said. "Saying that I am making work that connects deeply to my personal narrative—that would not have happened without my conversation with [Sillah and Hite] and the vulnerability I felt in that safe space." Besides exploring more personal themes, she also started experimenting with collages, which she said she adopted after seeing "amazing Black women doing work in different mediums."

They worked through the first part of the semester on pieces they planned to show "in highly populated areas at Bowdoin [like Smith Union, Thorne Dining Hall, the Visual Arts Center, and the Quad]—places that would force the student body to engage with themes and concepts that came out of the work we were producing," Kearney said.

“That always was the goal, to have an artist collective at Bowdoin that lived on.”

—Amie Sillah ’20

But then the pandemic happened (that little phrase that sent so many people reeling and plans derailing).

"We had to get very creative very fast!" Hite said. They did a "180," and decided to publish a book. "It was one of the best ideas we could have come up with," she added. The catalog includes text and images, as well as a transcribed interview between the artists and Chartouni.

In addition to publishing In, Not Of..., they shared their work and processes on social media. The upside to this is that these venues have given them a wider audience than any on-site, temporary installation at Bowdoin could have.

Today, the Black Lady Art Group collective is still a part of all three of their lives, and they regularly check in with each other about their art and career trajectories, with technical questions, for marketing ideas, for résumé advice. While art school may lie ahead for them, they're all currently working: Hite is the social media coordinator for Broadcast Music, Inc. (BMI), based in New York City; Kearney is a Lead for America fellow with The Art Effect in Poughkeepsie, New York; and Sillah works for the TEAK Fellowship in New York City, an education nonprofit that helps young low-income students. They all plan to forge lives and careers around artmaking.

They also hope that the momentum the Black Lady Art Group began at Bowdoin—to provide a foundation of support for Black female artists—will continue.

"We want to find a way to really give life to the Black Lady Art Group, to give it a structure to pass it on. We want it to live beyond us for other Bowdoin students," Sillah said. "If it lives and dies with us, it defeats the purpose. That always was the goal, to have an artist collective at Bowdoin that lived on."