Capturing Data on Ice

By Tom PorterWhen he was playing in goal for the Bowdoin hockey team back in the ’90s, Dave Lehanski ’96 often thought, “Why are there only two stats for goalies? Why just goals against average and save percentage?”

“There has to be a better way to look at goalkeeper action, given how no two shots are the same,” the economics major would say to himself. Two and a half decades later, Lehanski is at the helm of a pioneering project that uses technology to capture not only everything the goalie does, but pretty much everything that happens on a top-level hockey rink.

Lehanski is executive vice president for business development and innovation at the National Hockey League. This season the NHL rolled out its innovative puck and player tracking technology at all of its thirty-one arenas, after limited deployment last season during the playoffs.

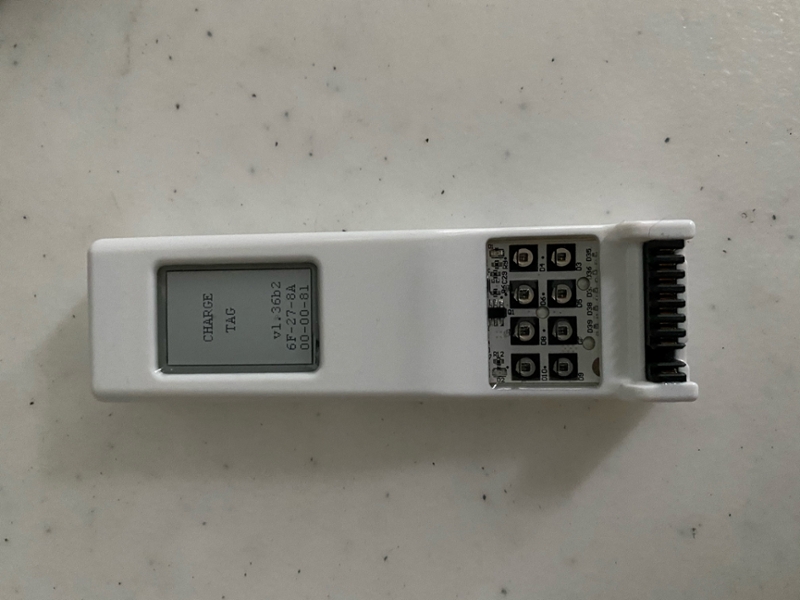

For Lehanski, this is the culmination of more than eight years’ work designed to transform the hockey fan experience and provide coaches and team managers with a wealth of valuable new data. “It’s an infrared-based system,” he explained. “Between fourteen and sixteen cameras are now positioned at multiple levels in every NHL arena to triangulate the position of the players and the puck.” This involves a brand new type of puck, although a lot of effort went into making it feel and act just like the old one, said Lehanski. The puck, which costs forty dollars instead of two, still weighs the standard six ounces but inside the vulcanized rubber casing it’s filled with circuitry and a six-hour battery, emitting infrared light sixty times a second.

The players, meanwhile, now wear a tag the size of a stick of chewing gum in the back of their jerseys. These emit infrared pulses fifteen times a second. The end result is a system that generates nearly one million three-dimensional coordinates and data points over the course of a typical game. The mountain of data generated by the new system enables the creation of new advanced metrics and statistics. “We now have the ability to better showcase the skill and speed of the players by showing, for example, how fast the puck is moving, how quickly a goalie reacts, the total distance players travel, how fast they travel, and so on,” said Lehanski. “Hopefully, this will attract more viewers and pull fans a little deeper into the sport, recreating the excitement of a live game,” he added.

The lightning-fast speed of an NHL game, as opposed to stoppage-filled NFL matches, for example, said Lehanski, underlines the importance this technology attaches to the creation of live data. And this has huge implications for those who like to bet on sports. “When we were developing this in 2012–13, there was no notion that sports betting would become legal in the US,” said Lehanski. Betting was legalized in 2018, and for hockey followers this new technology opens up a world of real-time options. “Previously, bets tended to be based on outcome, but now with all this data, you can bet on who the faster skater is, distance traveled, who will score next, who the next power player is, and more.”

Amid all this new technology, however, one time-honored hockey tradition still stands. Despite the increased cost and complexity of the new puck, said Lehanski, any that end up in the stands can still be taken home by lucky fans as souvenirs. Those souvenirs will simply be worth a little more from now on.