Online Teaching: Pulling Off a Pandemic Experiment

By Rebecca Goldfine

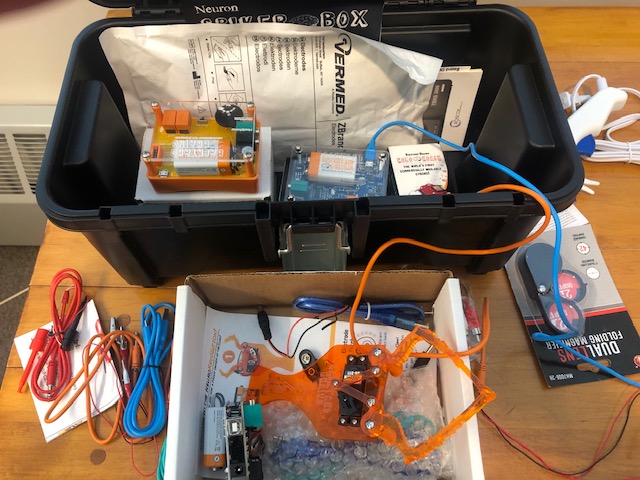

Working through July and August, nineteen lab instructors pulled together hundreds of laboratory kits for students—some with ingenious self-designed gadgets—that they mailed to addresses around the world.

They recorded hundreds of videos and wrote up new lab manuals explaining equipment, scientific concepts, and the correct set-up for experiments. Others tromped to sites across Maine to capture video and photography for field-based classes.

Because of these efforts, students this semester are able to do things like investigate the physics of inertia, observe enzyme reactions, and learn about terrestrial and marine environments.

In more typical semesters, Bowdoin science students participate in weekly three-hour classes in a teaching lab (or field trip), where they take advantage of sophisticated equipment, a variety of chemicals, safety gear, and Maine's outdoors. Lab instructors buzz around them, helping students troubleshoot as they set up experiments and collect data.

So when President Clayton Rose made the announcement in late June that all classes (except first-year writing seminars) would be taught remotely this fall to help prevent a viral outbreak, the College's lab instructors went into overdrive to create new labs for an online environment.

"I had to go into high gear," biology lab instructor and lab director Pamela Bryer said. "You have to think not only about what a lab is for—experimental design, data collection, data analysis, scientific writing, and quantitative skills acquisition—but also how to still have students learn those things. I was adamant that it be hands-on."

Bryer rejected one possible solution: that students use online software, which might have them mousing over a pipette and petri dish, for instance. "When you are doing stuff hands-on and make a mistake, you can redo it to understand where you went wrong. So there is a lot of learning that comes with that," she said. "My goal was to do something hands-on, interesting, fun, and safe because students had to be able to do it in a dorm room or at home."

Bowdoin's lab instructors don't normally work during the summer. Their wages for July and August were subsidized by a $25,000 award from the Davis Educational Foundation, which supports undergraduate colleges and universities in New England's six states.

"The lab instructors had a number of tasks to accomplish this summer," wrote Associate Dean for Academic Affairs Elizabeth Pritchard in a report she sent to the foundation this fall. One big time commitment was attending "workshops for online course design and delivery that reflected the key features of Bowdoin’s pedagogy."

One of the workshops that biology lab instructor Shana Stewart Deeds participated in was offered by the Black Minds Matter program. "It was a nationwide workshop based on the tenets not just of black lives matter, but black minds matter," Deeds said. "We had to redesign our courses anyway, and it was important to me to make sure we’re being inclusive in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math), and add elements that will be helpful to all students." These elements included creating assignments for different kinds of learners and adding more opportunities for student to connect with her and other classmates. Deeds also helped write the biology department's statement on anti-racism.

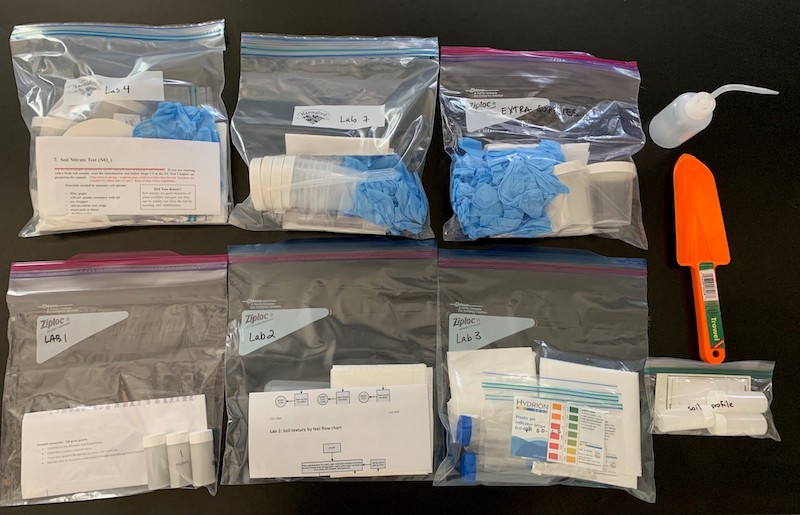

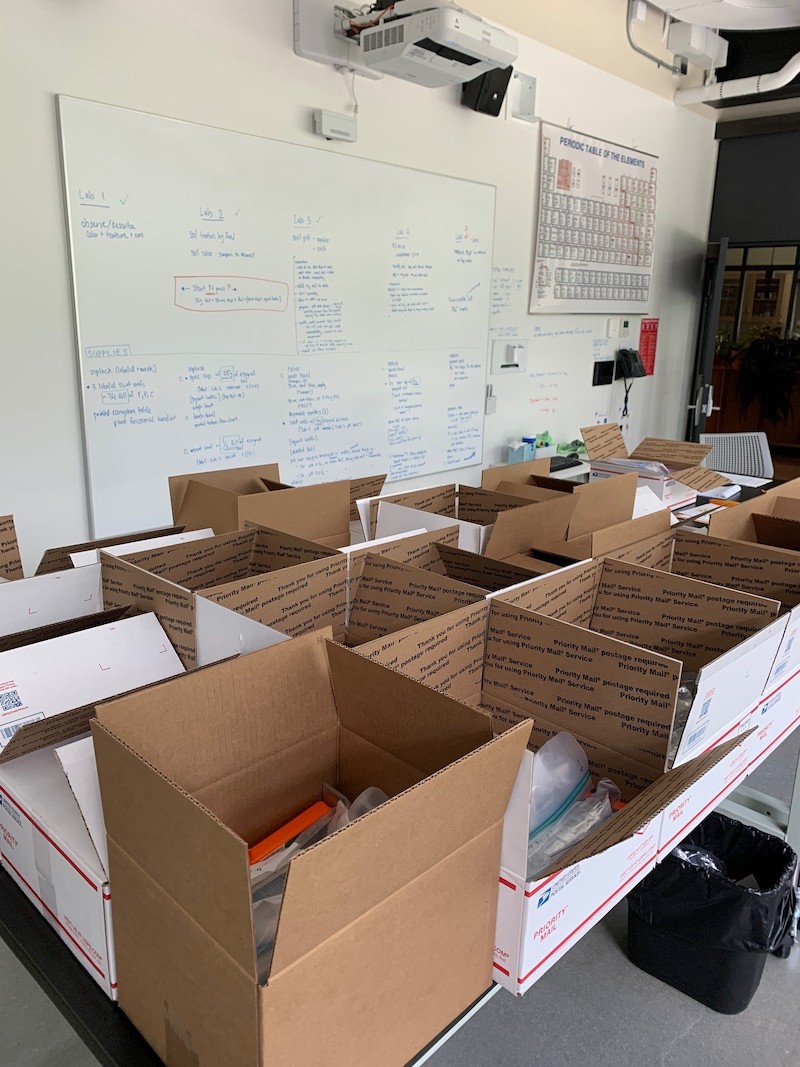

Not only did lab instructors attend workshops throughout the summer (many offered by Bowdoin), create new labs and lab manuals, and make hundreds of instructional videos, data tables, and hint pages, Pritchard said in her report, they also pulled together approximately 500 lab kits (aka "care packages") filled with gear that students could use to set up home labs.

The unusual circumstances that propelled this flurry of activity also inspired ingenuity and innovation among the instructors. Their commitment to sourcing everyday materials for the labs saved the College thousands of dollars. Plant physiology lab instructor Jaret Reblin, for example, went on Amazon to buy fake blood IV bags for Zombies for his stemflow lab, to demonstrate how water is transported through leaves.

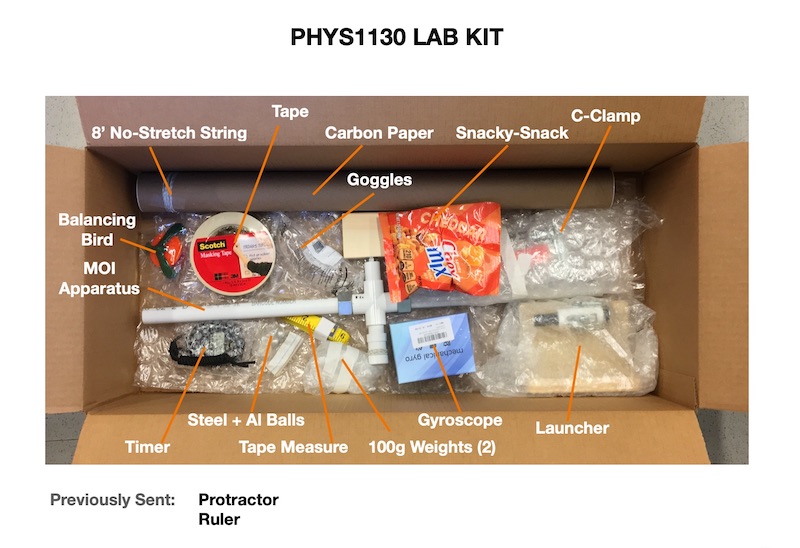

In pre-pandemic days, students in the introductory physics class PHYS 1130 learned how to use a couple of pricey gadgets to study the laws of inertia and projectile motion. To supply each of the fifty students in the course with these apparatuses would have cost more than $20,000, estimated physics lab instructor Paul Howell.

"Well, heck," Howell recalled thinking. "I think we can build these things ourselves." With input from physics professors Mark Battle and Tom Baumgarte, Howell partnered with Bowdoin machinist Ben King to construct their own version of a gadget for the Moment of Inertia lab made out of PVC piping, ball bearings, and wood. "We went around and around on the design of this thing before we got it right," Howell said. Each one cost about $15 to make.

And "it works a little better, too," Howell said, compared to the original. It just looks a bit less fancy. "We might very well use this once the world comes back to normal."

Nur Schettino ’24, a student in the physics class, spoke via Zoom from his home in Alexandria, Egypt, just hours after finishing the Moment of Inertia lab. "That was my favorite lab yet," he said. "It was the first time we used an apparatus, and I was able to conduct multiple trials and take measurements."

Howell and King also built a launcher for steel or aluminum balls so students could experiment with projectile motion.

They made enough of both devices for every student—about 120 in all. The total cost to build the two items was $2,400 in materials, saving the department $17,850.

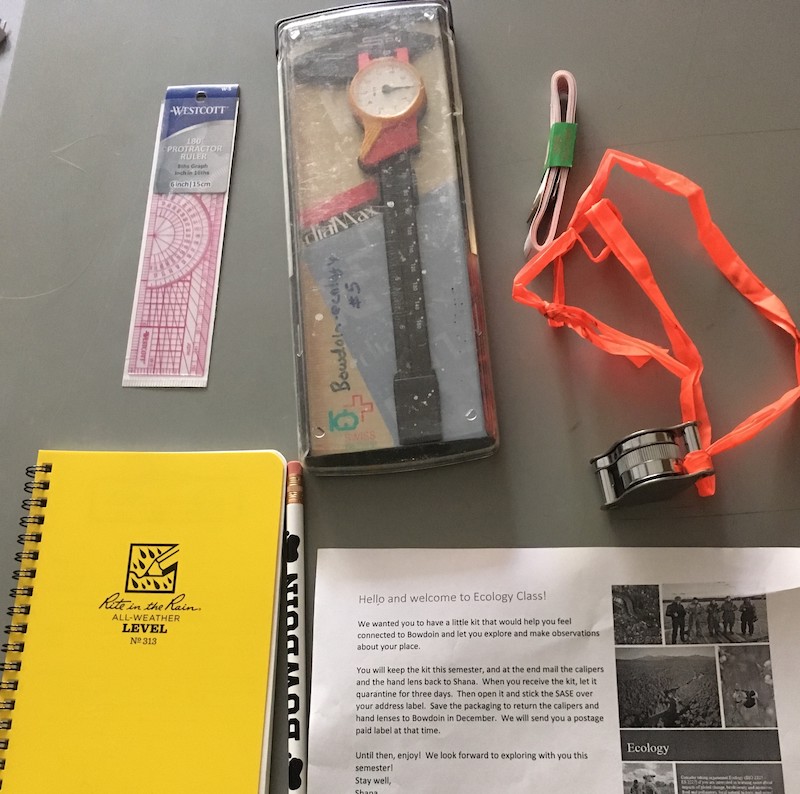

"There was also a lot of compassion and well wishes in those kits we sent!" biology lab instructor Shana Stewart Deeds said about the lab kits she sent to students in the course Ecology. "More than anything, we wanted students to see they could explore natural history in their place with a few simple tools, and to know that we were thinking of them and missing having them in in-person labs."

When the world is not beset by a deadly virus, Bryer normally uses her free summers to teach AP high school teachers. That experience was an asset to her as she prepared for an online semester of BIOL 1109 Scientific Reasoning in Biology. "It helped me a lot, because many of the teachers I work with are from small schools in Maine, and they don’t have equipment budgets," she said. "So I developed several labs this semester where students could get the data they needed without expensive materials."

What Bryer didn't anticipate was how difficult it would be finding supplies during a pandemic. "With lots of colleges and high schools going remote, plastic graduated cylinders were hard to get without paying a ton for them," she said. "Trying to find those occupied days and days."

Orders were slow to be filled. Shipping was delayed. And tracking down eighty-four packets of yeast was even more challenging, as people stuck at home suddenly took up baking bread as a hobby.

After Bryer accumulated everything she needed—that is, after multiple trips to Target, Walmart, and Hannaford—she packed up eighty-four boxes for delivery. This included distributing 10,000 individual pieces into 1,000 bags, separating and bagging 3,700 seeds, and weighing out nontoxic chemicals into hundreds of packets.

Based on feedback she's heard from Residential Life proctors, first-years in her biology class have started to do their experiments together in shared common areas. "I have found out that it's been a bonding experience for first-years, so that's been nice," Bryer said.

Both Bryer and Howell say their efforts—particularly all the instructional videos they made—will benefit future labs. But they are looking forward to a return to the status quo. "We're in lab for three hours with them each week, and there are a dozen students, and I'm running around, solving problems. I really get to know them well, and I do miss that," Howell said.

For the class Behavioral Neuroscience Laboratory: Affective Neuroscience, Neuroscience Laboratory Instructor Anja Forche and Assistant Professor of Psychology and Neuroscience Jennifer Honeycutt sent two packages to their students this semester. One was a sheep brain-dissection kit, the other a rat brain-mounting kit.

"In a typical semester, students would be running experiments in the lab, learning how to handle rodents and run them in behavioral assays, and they would also have an opportunity to section brains, mount them onto slides, and quantify neuronal changes underlying affective (or emotional) behaviors," Honeycutt said. "With the pandemic forcing us to adapt the course to an online platform, we wanted to ensure that students were still able to have hands-on experiences that define a lab course."

In their most recent lab, Forche and Honeycutt ran a synchronous Zoom session with students, so together they could organize brain sections in anatomical order and mount them onto slides. At the same time, they used Slack to allow students to share photos of their brain sections. In this way, the instructors provided real-time feedback both verbally over Zoom and visually by using the iPad and Apple Pencil to annotate their photos.

"This approach to a hands-on lab has gotten a lot of traction on Twitter, with interest from other professors looking to incorporate budget-friendly hands-on experiences in their online courses for next semester," Honeycutt said.

Last week @BowdoinCollege students mounted rat brains onto slides from their homes for my behavioral neuro lab course! @AnjaForche and I loved putting this lab together & had so much fun seeing our students beautifully organize and mount their brains! 🐭 🧠 🧫 #remotelearning pic.twitter.com/SP9omTXqqf

— Dr. Jennifer Honeycutt 🏳️🌈🧠👩🏼🔬 (@ohambiguity) November 10, 2020