Online Teaching: How to Bring Maine's Sea to Students

By Rebecca Goldfine

In more typical years, Biology of Marine Organisms, or BIOL 2319, takes advantage of Bowdoin's location on the coast of Maine to introduce students to marine ecology. Throughout the semester, the class makes at least five field trips to nearby rocky intertidal zones, mudflats, and salt marshes.

After learning this summer that their class would be online in the fall, Visiting Assistant Professor of Biology Justin Baumann and Biology Lab Instructor Bethany Whalon began thinking up ways to bring the coast to students living around the world, some of them landlocked and far from the ocean.

"There are a couple of issues, of course, with being online," Baumann said recently. "Students aren’t here and we can’t take them out to poke around and learn, which is the best way to experience the marine environment."

But with all situations that initially appear gloomy, there are often unexpected bright spots. "The upside is that we can explore marine organisms around the world," continued Baumann, who is an expert on coral reef ecophysiology. "So we might as well check out some other places, like coral reefs and tropical ecosystems."

Baumann will show his own videos from his field work in the Caribbean, as well as share livestreamed videos of deep sea organisms and whale fall ecosystems (which are created from whale carcasses falling great depths to the sea bottom).

Though the internet has opened up the world's oceans to the class, the course is still grounded in Maine's environment. Baumann and Whalon spent many hours this summer traipsing around the seashore with a GoPro camera to develop a trove of videos, photographs, and data to share with students who couldn't be here in person.

They are also encouraging students to become experts on the ecosystems in their own backyards.

Recreating Maine field labs

So far, Baumann and Whalon have visited the Giant's Stairs in Harpswell, Ocean Point in East Boothbay, Bowdoin's Schiller Coastal Studies Center, and a salt marsh in Brunswick. With Baumann working the camera and Whalon serving as nature guide, they have attempted to recreate these habitats digitally as best they can.

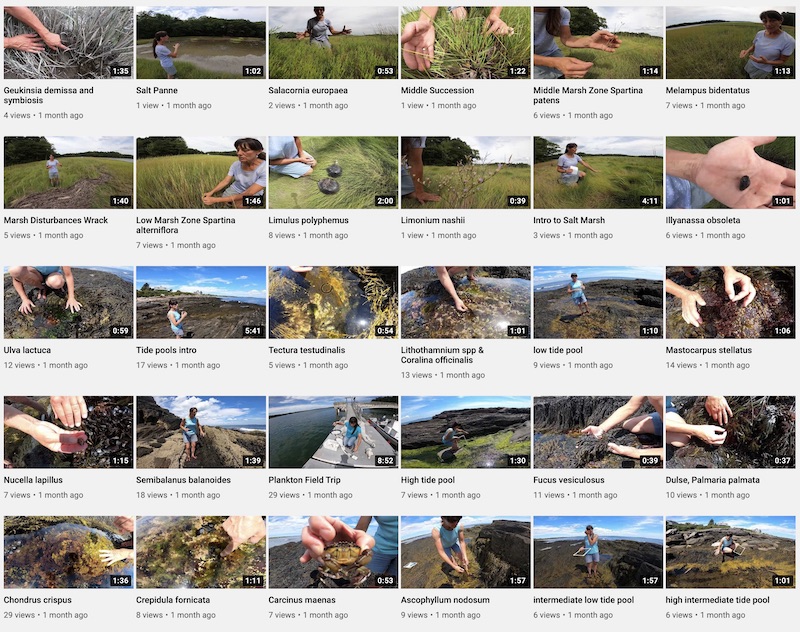

All together, they have made nearly seventy videos about a range of subjects—from subtidal creatures, plankton, and field ecology methods to how a salt marsh recovers from a storm.

"We are trying to still get them out there and to show them Maine," Whalon said. "We’re trying to give them the Bowdoin experience, even though they are not present."

By virtually trailing Whalon and Baumann on YouTube, students learn to identify marine organisms like bivalves, crabs, snails, barnacles, and algae. They study how tidal pool water chemistry and composition are affected by factors such as water depth, the time between high tides, and the pool denizens that contribute to or remove oxygen from the water.

They learn how ocean wave energy affects rocky substrata, depending on the site's exposure and steepness of slope, and how this influences the organisms that live there.

They also investigate a low-nutrient salt marsh. In videos Whalon and Baumann made of their marsh visit, Whalon discusses hardy sea grasses, horseshoe crabs, and carnivorous whelks, among other topics.

"We're trying to teach students about how all the animals living here adapt to stressful conditions—what do they eat, what eats them—and how every single species on this planet has a role to play in their ecosystem," Whalon said. "So what is that role? Does it provide food? Does it provide canopy cover? Does it provide habitat?"

Alexia Brown ’21, who is taking the class from her home in New York City, said the weekly video forays are "the closest thing to an 'escape to the sea' from the four walls of my apartment." But she did admit, too, that "in all honesty, it sometimes makes me feel a little down that I couldn't physically be there to see and experience those areas like I would have been able to do if I was on campus."

'Ecology Near Me'

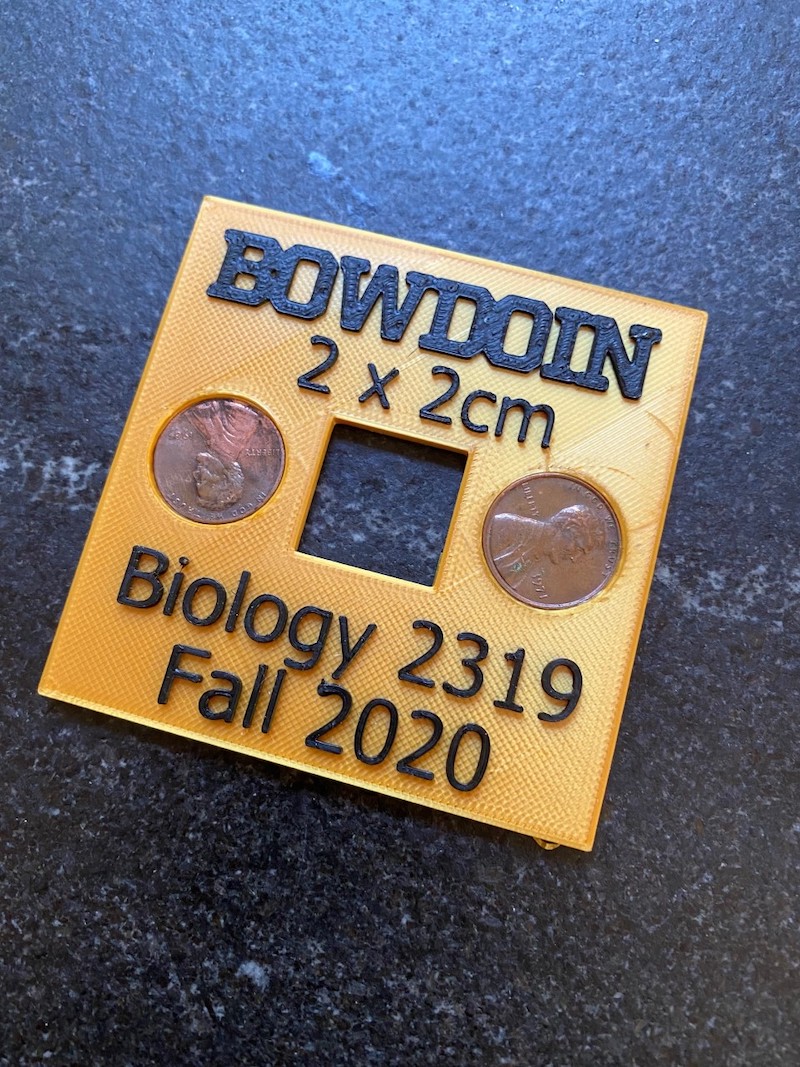

Before the class began, Whalon and Baumann sent out what they affectionately call "lab care packages" to each student. Included was a ruler, caliper, tape measure, colored pencils, a Rite in the Rain notebook, small magnifying glass, snacks!, and two quadrats—one of them customized for the class. A quadrat provides a simple way for field ecologists to survey species in a specific area.

With these tools, students can head outside no matter where they are to study the environment around them. "They can learn about ecological systems in any setting," Baumann said. "How do you really learn environmental science? You basically go to the environment and watch it."

Baumann and Whalon asked the students to find one small area—perhaps a portion of sidewalk with weeds poking through cracks, an urban garden, a spot near a pond or in a forest—and observe it over eight weeks.

"They'll use a transect tape and quadrat and do what we would do in the field," Baumann said. "I want them to explore whatever is around them, and see how things interact and how things change, and why things change."

By using apps like iNaturalist and Seek, and by consulting more traditional taxonomy books, the students are also expected to identify all the species in their ecosystem.

"The more we look at the world around us, the more we see," Whalon said. "They’ll start noticing things they never saw before. It doesn't matter where they are, what they find, or what organisms are living around them. They'll start realizing that the weather, humidity, time of day, and season affect everything, and that there is a rhythm to everything."

Each week, the students make a new video of their transect and upload them to Flipgrid, a video discussion and sharing tool. Since the students live across the world—in Nantucket, Vermont, Maine, Washington, Virginia, New York City, Colorado, Minnesota, and New Zealand—they are sharing discoveries about diverse ecosystems.

Alexia Brown ’21 is observing a garden plot tucked in amid apartment buildings. She says the Ecology Near Me video project gives her an excuse to head outside of her NYC apartment. "I'm learning more about the ecosystem that I lived around yet ignored my whole life," she said. "I'd always assumed that by living in NYC, there are very few things that are 'natural' about my environment."

"I've been really impressed with how engaging and interactive the course has been overall. I love the energy that Justin and Beth convey over Zoom; I think that's not easy to do and they are totally nailing it. It is a bummer that we don't get to do a field-based course in Maine, but I really appreciate how the course is pushing us to explore our local surroundings and I think that it is strengthening our ability to be scientists in a lot of different environments as opposed to a pre-defined 'lab' environment." — Anneka Williams ’21

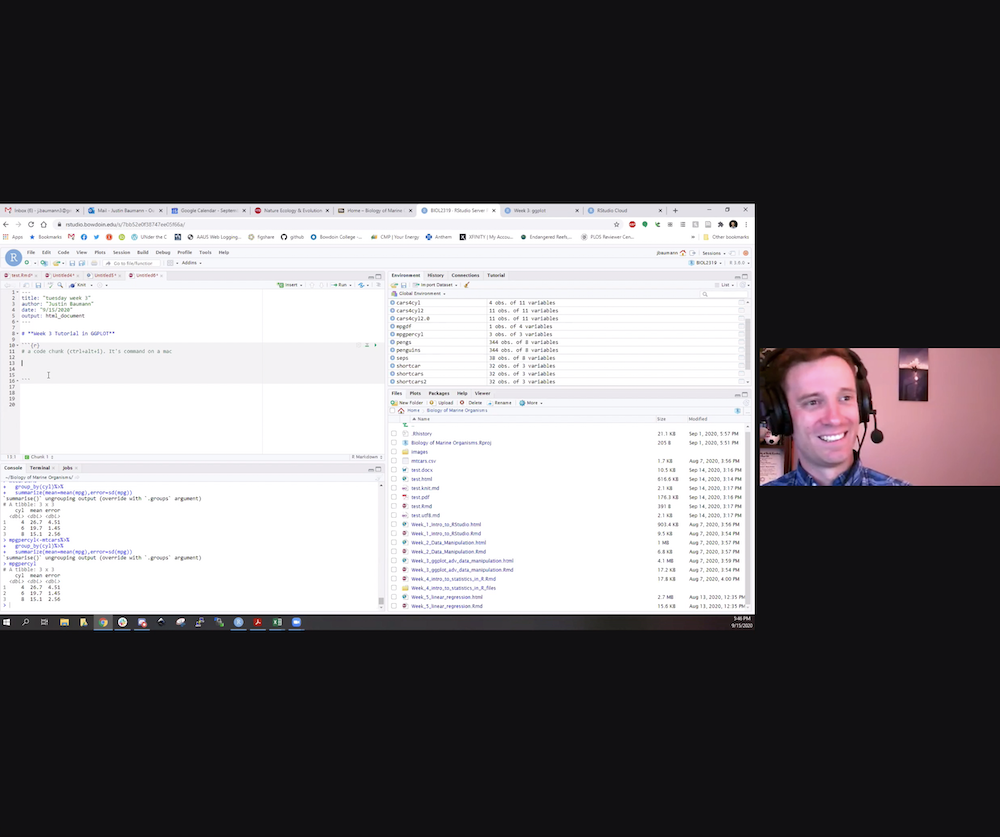

In addition to practicing field ecology techniques, students in the class are learning R, a statistical programming language, to analyze their data and reveal patterns in their findings.

"These are transferable skills they might as well learn, since we can’t teach them how to do comparative anatomy or whatever we would normally do in the lab," Baumann said. "Instead, we can teach them another skill that they can learn remotely." The class has two teaching assistants—Bowdoin students who are familiar with the statistical coding program—to provide additional help.

The class curriculum also puts an emphasis on scientific writing, and the students will prepare two in-depth papers. One assignment asks students to generate and test a hypothesis based on four years of data from Maine tidal pools. "They'll focus their analysis on answering a question," Baumann said. "I want them to be driven by a question."

For their capstone projects, the students are expected to write a detailed scientific paper based on an analysis of data from either a coral reef or a Maine tidal ecosystem, with an introduction, methods section, results, and discussion.

"We want them to have tangible, usable skills," Baumann said. "And an appreciation of the world around them."

Interested in how other Bowdoin faculty are teaching online? Read about Vyjayanthi Selinger's Intermediate Japanese class and Abigail Killeen's new Acting for the Camera class.