What to Expect This Election Cycle: Government Professors Weigh In

By Tom PorterThree Bowdoin government professors recently sat down (remotely, of course!) for a discussion about what might happen after next week’s presidential election from a constitutional, electoral, and judicial perspective.

The event was called Anticipating the Unanticipated, and it featured Thomas Brackett Reed Professor of Government Andrew Rudalevige, Assistant Professor of Government Maron Sorenson, and Professor of Government Michael Franz. The moderator was Sarah Chingos, Associate Director for Public Service at the McKeen Center.

What they said:

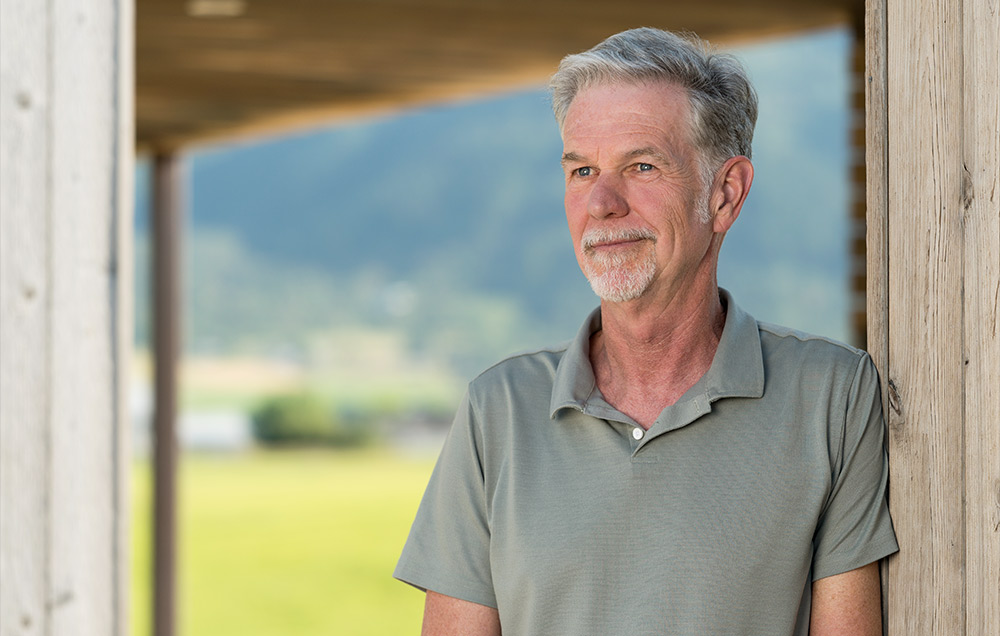

Rudalevige studies American political institutions, with an emphasis on the modern presidency and interbranch relations. Although election day is November 3, he explained, “national election day is not national or ‘one day.’” There are fifty-one separate elections in the states and in the District of Columbia, he pointed out.

The process is spread over weeks, or months in some cases, said Rudalevige, with early voting in North Carolina starting on September 4 and in most other states by mid-October. The timeline extends well beyond election day, he explained. Crucially, he reminded us, the president is not decided by the national popular vote, but by the Electoral College, which comprises 538 electors, who are expected to vote in line with the popular vote in their state. The electors themselves meet in their state capitals on the first Monday after the second Wednesday of December to formally cast their votes. This year, that is on December 14. Looking even further ahead, Congress will meet on January 6 to tally the votes, said Rudalevige, before the winning candidate is inaugurated on January 20, 2021.

This process, he explained, is normally “invisible” to ordinary voters. “We don't pay much attention to it. We watch TV on election night, we see states light up red or blue, someone declares victory, someone concedes—but not always.” One example he cited was the very close presidential election in 2000, which all came down to electoral votes in Florida. Having at one point seemed poised for victory, Democratic challenger Al Gore went on to concede the race to incumbent George W. Bush on December 13—a full thirty-six days after election day.

Professor Sorenson, a specialist in judicial politics, went into more detail on the Bush-Gore election of 2000, which was decided on the finest of margins. She described the legal battle that erupted between the two camps over whether to allow the manual recount of ballots in four key Florida counties. “Things were very messy,” she said. The conflict was resolved by the involvement of the US Supreme Court, which on December 12 overturned a decision by the Florida Supreme Court that would have allowed the manual recount. This intervention, she explained, effectively handed victory to George W. Bush.

Sorenson said there are a couple of lessons to be learned from the 2000 election. First, if the Supreme Court issues something called an “emergency stay,” that’s a pretty good indication they’re going to get involved in the election. “The second lesson,” she continued, “is this idea that the state should have clear guidelines in effect for determining voter intent.” With the high number of absentee and mail-in ballots this year due to the COVID-19 pandemic, election officials should be prepared for challenges and requests for manual recounts in some precincts.

Professor Franz talked solely about the upcoming 2020 election, which has attracted “astronomical” levels of ad spending due to the intense interest in the outcome. Franz’s research interests include campaign finance, political advertising, and interest groups. He also studies voting behavior, and this election, he said, is on course to show the highest turnout in more than a century, with close to 70 percent of the electorate expected to vote.

He talked about the reliability of polling, especially as so many pollsters got it wrong in 2016 by forecasting a Hillary Clinton victory. In one sense, though, Franz said, the opinion polls were correct in 2016. “The national polling was actually pretty good. It showed Clinton would win the popular vote, and she did.” It was at the state level, however, that the polling was not as good, especially in battleground states like Wisconsin and Pennsylvania, where polls did not account for underrepresented working class white voters in their samples. This time around, however, Franz believes pollsters have accounted for that demographic, which would be good news for Joe Biden, who is shown to be ahead in many of those key states.

"We watch TV on election night, we see states light up red or blue, someone declares victory, someone concedes—but not always." Prof. Andrew Rudalevige.

Watch the Video

Anticipating the Unanticipated was sponsored by Bowdoin Votes, the Department of Government and Legal Studies, Bowdoin Public Service, and the McKeen Center for the Common Good.