Jazz and #MeToo

By Tom PorterTracy McMullen began her recent presentation with an attention-grabbing anecdote: “Perhaps I can count myself lucky,” she said, “that thus far only twice have I been forcibly kissed and only once had my breasts forcibly grabbed in the course of my work as a saxophonist.”

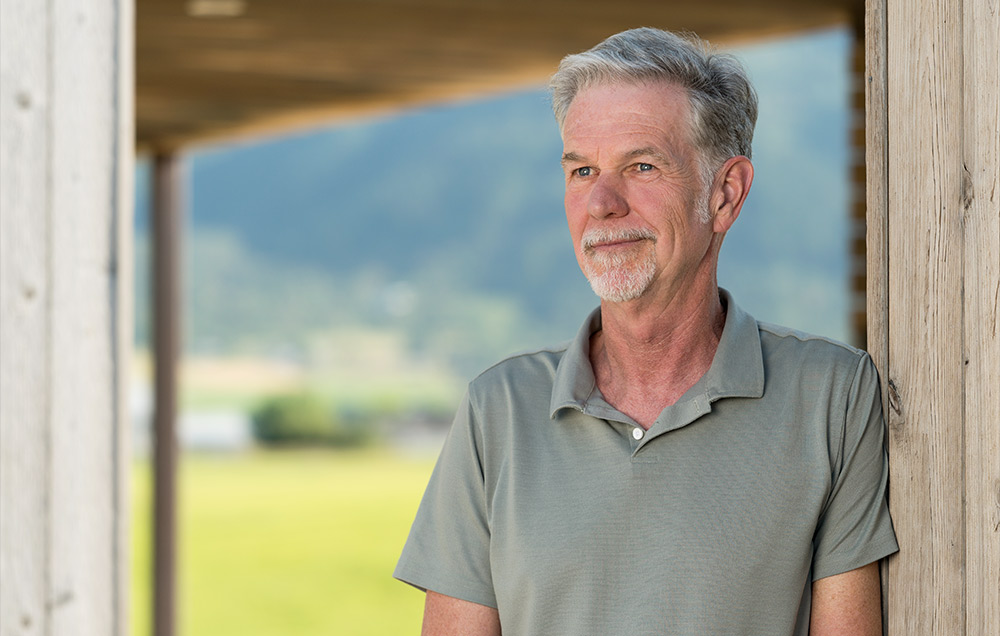

McMullen is professor of American vernacular music and a noted jazz musician and composer. She’s currently working on a book about diversity and inclusivity in jazz and education and recently delivered a seminar to her faculty colleagues titled “What Love? #MeToo and Jazz Romanticism.” She is essentially calling for attitudes in the jazz world toward women musicians to change. One might think of jazz circles as being relatively liberated and easy-going, especially when compared to the perceived stuffiness of the “straight” world of classical music, but since its inception as an art form, commented McMullen, jazz has been rife with sexism.

She told the audience about one of the times she was assaulted. It was at a jazz symposium ten years ago, when someone she described as a very famous male musician in the jazz world—another saxophonist—made her the object of unwelcome advances. McMullen didn’t want to identify the culprit, merely to use the story to illustrate a problem which is widespread and deep seated. “[T]his behavior is exemplary of a pervasive and consciously sustained narrative that harasses women and keeps them marginal to jazz,” she said.

Other examples cited by McMullen included an excerpt from an exchange posted on social media between a white jazz college history instructor and a black musician, both male: “ 'Cats used to say…if you can’t seduce a woman with your playing you ain’t playin’ sh*t!’ wrote the instructor, to which the musician added a comment about how another musician once told him to 'play to the b**ches,' a comment which elicited a Facebook 'ha ha' from the instructor," said McMullen. “Plucking sexism from the jazz air is as simple as checking that day’s Facebook posts or someone’s blog,” she added. “That jazz instructor’s view of the jazz world is part of a long story that has encouraged men’s ignoring and harassment of women in jazz.”

There’s a racial dynamic at play here too, explained McMullen. It’s what she described as the “romanticizing of blackness and its attendant sexism” by many white males in the jazz world. By this, she said she means “the white man’s desire to be cool, to be accepted by the black man. To show that he gets the music, that he is woke and hip and not racist at all. And yet, this love is played out via misogyny and power over women by making them 'the other' to them both, the common enemy, if you will.” Such an attitude propagates the idea that jazz—particularly instrumental jazz??—is almost exclusively a male preserve, something women don’t play or appreciate.

“So, I want to declare this to all jazz men,” responded McMullen. “Girls and women LOVE jazz like you do. Women also fall in love with the music. Women also want to seduce people through their music.” There are positive developments, she said, such as the “significant changes” being undertaken to address sexism and harassment by authorities at Berklee College of Music—that preeminent training ground for America’s elite jazz musicians. There is currently a move by faculty there to achieve gender parity by 2025.

McMullen also appealed to the men of the jazz world to take active measures to purge sexism—to “invite women into their groups; don’t harass them; learn how to teach girls, women, and others who may not feel comfortable in typical jazz education settings that encourage competition and centralize boys.”

McMullen suggested some “handy synonyms” to replace commonplace terms with sexist overtones: “Instead of cats or guys, say musicians. Instead of sideman, say collaborator. As jazz is taught to the next generation,” concluded McMullen, “we need to think about what is being passed on.”

Professor Tracy McMullen’s 2019 book, Haunthenticity: Musical Replay and the Fear of the Real (Wesleyan University Press) contextualizes live musical reenactments (pop tribute bands, jazz revivals) within postmodern conceptions and fears about identity and difference.