Stitches in Time

By Tom PorterIn early April, a selection of these embroideries will be flown back to Labrador with three Museum scholars—Susan Kaplan, the Museum’s director; Genevieve LeMoine, the curator; and Katie Donlan, a curatorial intern—in an effort to document the history of this art form from the Inuit perspective.

The trip should last nearly three weeks. “It’s a project that’s been years in the making,” says Donlan. It began, she explains, with a visit by Kaplan to Labrador’s Inuit communities in 2014. The bigger story, however, goes back further than that. Much further. “We can trace it to the late 1700s, when Protestant Moravian missionaries from Germany and England first came to Labrador,” says Kaplan.

“Labrador Inuit have a very distinct artistic tradition, which has only recently begun to be studied.”

—Professor Susan Kaplan, director of the Museum and Arctic Studies Center

Moravian Influence

The Moravians stayed in this part of Atlantic Canada, setting up schools and churches, leaving a cultural influence on the Inuit that can still be seen today through music, architecture, and in these embroideries—something that sets them apart from other indigenous peoples in the Arctic, explains Kaplan. One legacy of the Moravians was a fondness for embroidery among Inuit women and children, something the Inuit adapted and made their own.

“These pieces are noticeably different from the European style, much more floral and decorative, and unique to Labrador.”

The Embroideries

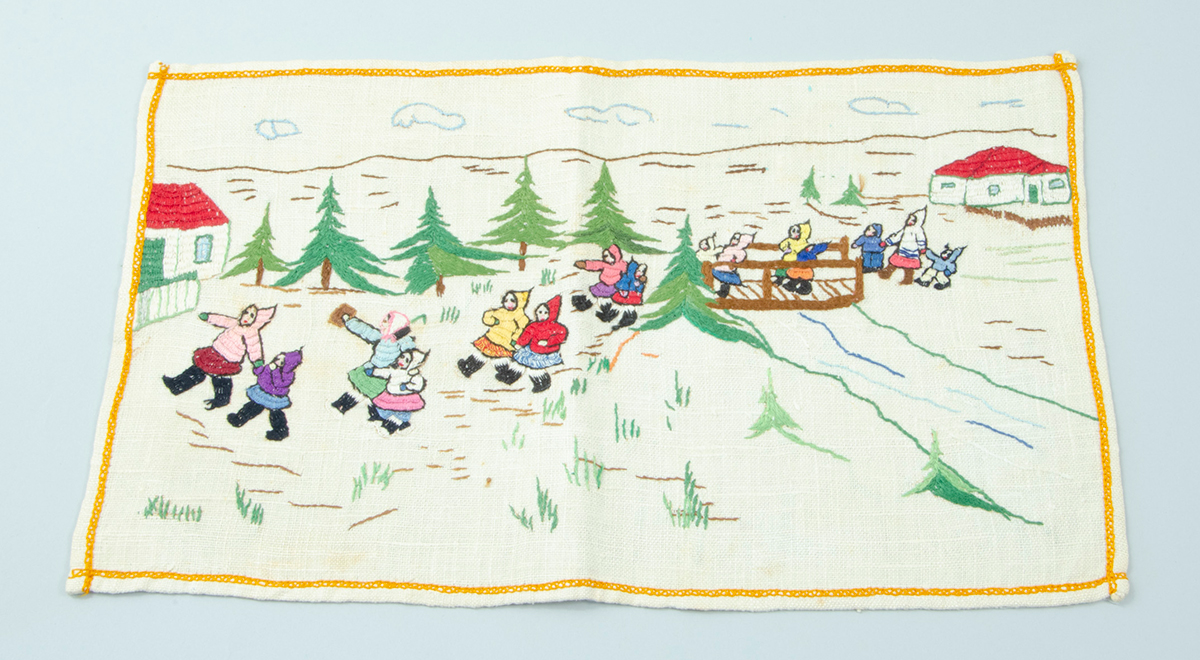

Other than the fact that the items were made in Labrador Inuit communities between the 1940s and the 1970s, not much is known about most of the collection. Kaplan describes the embroideries as “almost like mini, visual ethnographies,” each one telling a story.

There are napkins, tablecloths, tea towels, table runners, and an apron, all with finely stitched colorful scenes on them. One tablecloth depicts a polar bear hunt from beginning to end. Another shows several outside activities common with the changing seasons: Tiny figures can be seen chasing butterflies, picking berries, and boiling a kettle.

Some of the embroideries include geographical information with landscapes and local buildings that still exist. Other scenes record memorable events: there are representations of MacMillan’s schooner, “The Bowdoin,” lying at anchor and sailing by a point of land. MacMillan himself is depicted next to a baby muskox—this was inspired by a photo taken further north, near Greenland, that LeMoine recognized from the Museum’s photography archives.

(Some of the embroideries were clearly used as everyday objects for a while by the MacMillans, says Kaplan, pointing to a couple of cigarette burns on a tablecloth.)

Going Back

The three women are in a classroom in Hubbard Hall above the Arctic Museum, with Bowdoin’s entire embroidery collection spread on tables around them. Their job is to pick out which of the ninety-two pieces will be carefully packed up in muslin for the journey north. Kaplan says they’re taking the unusual step of transporting the items from the collection to Labrador because of the excitement generated on the last visit to the region twelve months ago, when they showed detailed photographs of the artifacts to community members.

“We had some very good photographic slides of the embroideries when we came last year,” Kaplan says, “but this proved frustrating for some seamstresses, who would walk up to the screen to look more closely and then want to touch it and study the back of the cloth. ‘We have to be able to hold it and look at the stitching in the back,’ they told us.”

This time, Inuit elders will be able to do just that—to hold the embroideries in their hands, study them, and feel them—in an experience which may jog memories and help unlock some of the mystery surrounding these finely crafted treasures.

“One thing we dream of is that some people will perhaps recognize the work of individual seamstresses, so we can identify the creators of some of these pieces.”

—Genevieve LeMoine, Museum curator

In 2020, construction will begin on a new home for the Peary-MacMillan Arctic Museum and Center for Arctic Studies—a sign of Bowdoin’s ongoing commitment to the Arctic region, a connection that goes back over a century-and-a-half.