DR Congo Embraces Democracy?

By Tom PorterFor the first time in its fifty-nine year history, the Democratic Republic of Congo may be about to experience its first peaceful, democratic transfer of power, following elections there last month.

As history professor David Gordon reminds us, however, there are many qualifiers to this assertion. For a start, the electoral process itself has been far from smooth, amid widespread allegations of fraud.

As history professor David Gordon reminds us, however, there are many qualifiers to this assertion. For a start, the electoral process itself has been far from smooth, amid widespread allegations of fraud.

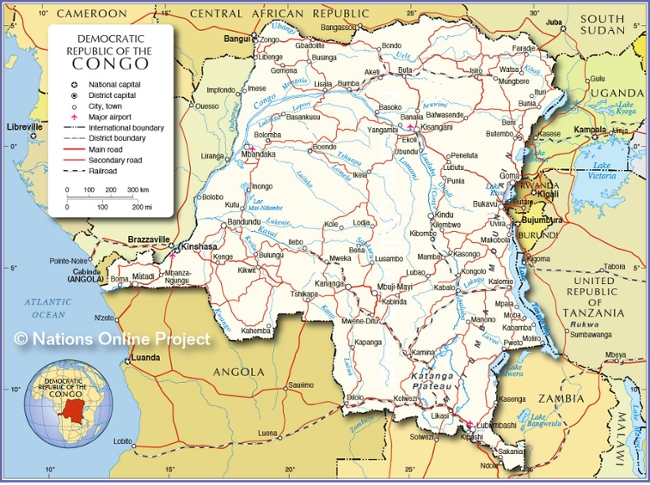

The vast central African country, formerly known as Zaire and also referred to as the DR Congo or DRC, has long been an area of specialization for Gordon, who calls it simply “the Congo.”

What's official?

Official election results proclaim the winner as Félix Tshisekedi, leader of the Union for Democracy and Social Progress, the oldest and largest opposition party in the country. Although he is an opposition leader, Tshisekedi has emphasized reconciliation toward outgoing president Joseph Kabila and his supporters, says Gordon.

The official runner-up is former oil industry executive Martin Fayulu, who leads a broad opposition alliance representing leaders from different parts of the country.

Felix Tshisekedi attends an election event in Kinshasa. REUTERS

Popular Players

One of Fayulu’s key allies is the intriguing figure of Moïse Katumbi, from the mineral-rich southern Katanga province. (Katumbi and his family were featured in Gordon’s first book about the fishing communities of the southern DR Congo and northern Zambia.)

After falling out with Kabila, Katumbi is currently living in exile. The son of a Greek Jewish fishing merchant, Katumbi became one of the DR Congo's wealthiest and best-known businessmen before he went into politics.

“He’s become an extremely popular figure," said Gordon. "As governor of Katanga Province he introduced effective political and economic reforms, while also establishing Africa's most successful soccer team and academy, TP Mazembe."

A Disputed Election

Outside observers, including most notably the Catholic Church, seriously dispute the results, reporting the Fayulu coalition to be the clear winner with around 60 percent of the vote—nearly twice the tally of the official results.

Foreign governments, including the US, Britain, France, and former colonial power Belgium, have all expressed concern. The sixteen-nation Southern African Development Community, meanwhile, has called for a recount, while Fayulu himself has lodged a formal appeal with the country’s Constitutional Court.

Gordon shares this widespread skepticism about the official results—part of the blame is said to lie with expensive, controversial, and unreliable electronic voting machines that the government implemented prior to the elections.

Voting has also been disrupted in the east of the country by an Ebola outbreak and by an ongoing insurgency.

I’m excited by what has happened in my home country and hopeful it will be the first democratic transfer of power since independence in 1960. I’m relieved that President Kabila’s candidate, Emmanuel Shadary, was not fraudulently elected, which would have led to chaos in the country.

I’m excited by what has happened in my home country and hopeful it will be the first democratic transfer of power since independence in 1960. I’m relieved that President Kabila’s candidate, Emmanuel Shadary, was not fraudulently elected, which would have led to chaos in the country.

I am aware of Martin Fayulu’s claims of electoral fraud, but unless substantial evidence is revealed backing up those claims, I’m happy to accept the official results.

I think the fact that Felix Tshisekedi’s late father was so popular definitely worked in his favor. Felix has made some astounding electoral promises—to unite the country and to improve the economic and social life of the nation. But I am waiting to see if he meant what he promised or if it was just for political reasons. Yes, there are many things to work out, but hopefully justice will be upheld.

—Espoir Byishimo ’22 was born in the Congo, and while a Rwandan citizen, considers himself Congolese at heart.

Kabila’s Grip on Power

Even if the presidential vote is successfully disputed, Gordon says Kabila will still maintain an unofficial grip on power because his political allies won the legislative election and, as a result, control parliament. The results of the legislative election are not being contested, says Gordon, and this presents the worrying prospect of Kabila, with the support of Tshisekedi’s party, rewriting the country’s constitution.

Kabila has faced repeated charges of corruption since assuming power in 2001. He took over after his president father, Laurent Kabila, was assassinated. He had ruled since 1997, when he overthrew the dictator and kleptocrat President Mobutu.

Photo: US Department of Defense, 2003

Joseph Kabila may be corrupt, says Gordon, but he has been tenacious, Machiavellian even, in his reluctance to give up his hold on power. Elections were originally supposed to be in 2016, but Kabila held up the process for two years. As violent protests erupted against his rule, notably in the capital Kinshasa and the south-central province of Kasai, Kabila used the unrest as an excuse to crack down on opposition groups and strengthen his hold on power.

“Even today,” says Gordon, “low-scale warfare continues in the east of the country, and that’s something that actually benefits the regime by ensuring the political opposition there cannot mobilize. Many political scientists working on the ground actually believe the regime is behind the insurgency in the east for this reason.” As Kabila prepares to relinquish power, don’t expect him to be too far from the center of the action, he warns.

A Troubled Country

"The political situation in the Congo,” explains Gordon, “has long been characterized as a shaky central leadership presiding over widespread interfactional violence.” It’s also one of the world’s poorest nations, with most of the population subsisting on little more than a dollar a day. Gordon quotes a recent statistic from the Gates Foundation, which predicts that, by 2050, forty percent of the world’s population living in poverty will be in the DR Congo and Nigeria.

Part of the tragedy of the Congo, says Gordon, is that it could be one of the world’s richest nations. As the largest country in sub-Saharan Africa in terms of geography and second largest in term of population, it has such great potential.

Photo by Julien Harneis, Flickr Commons.

“Firstly, there’s huge mineral wealth—gold, diamonds, copper, and uranium, as well as coltan and cobalt, which are used in the manufacture of mobile phones and the batteries that power them. There's also this vast river system, so the land is fertile with immense potential for hydroelectric power."

Instead of enriching the country, however, these resources have merely incentivized warring factions. With thousands killed in the last four years and millions uprooted, the United Nations has warned of a humanitarian disaster of "extraordinary proportions" in parts of the country. Yet conflict in the Congo is driven by much more than resources, says Gordon.

"The Congo is so vast that to say anything about it is bound to be a generalization. There isn’t space here to explain the various conflicts, but one key factor is a lack of centralization. Apart from the weak central government and an unreliable military, the Congo also suffers from a highly compromised infrastructure,” says Gordon. “It’s not connected organically. For example, the southern part is more linked to southern Africa than to other parts of the Congo; the eastern part has more ties to Rwanda and the Great Lakes region, and so on, while to travel overland from the political capital Kinshasa in the west to the economic capital Lubumbashi in the south is almost impossible.”

Regarding this latest chapter in the history of the country, Gordon says that, while the elections are a significant event, it’s too soon to judge whether they are a major turning point in the Congo’s struggle for democracy. Fraudulent or not, however, one thing is for certain: elections did take place and the Congolese people did vote for change. Whether any change will happen remains to be seen.