A Sociologist and a Senior Collaborate to Update Research on Adverse Childhoods

By Rebecca Goldfine

Because surviving a difficult childhood has such powerful lifelong repercussions, many institutions—from courts to medical clinics—rely on a brief, 10-question ACE questionnaire to determine people's childhood hardships. The higher the score, the more likely someone is to show its effects, including chronic disease, depression, and addiction.

But two Bowdoin researchers are arguing that the ACE survey, though vitally important, has serious limitations that must be examined.

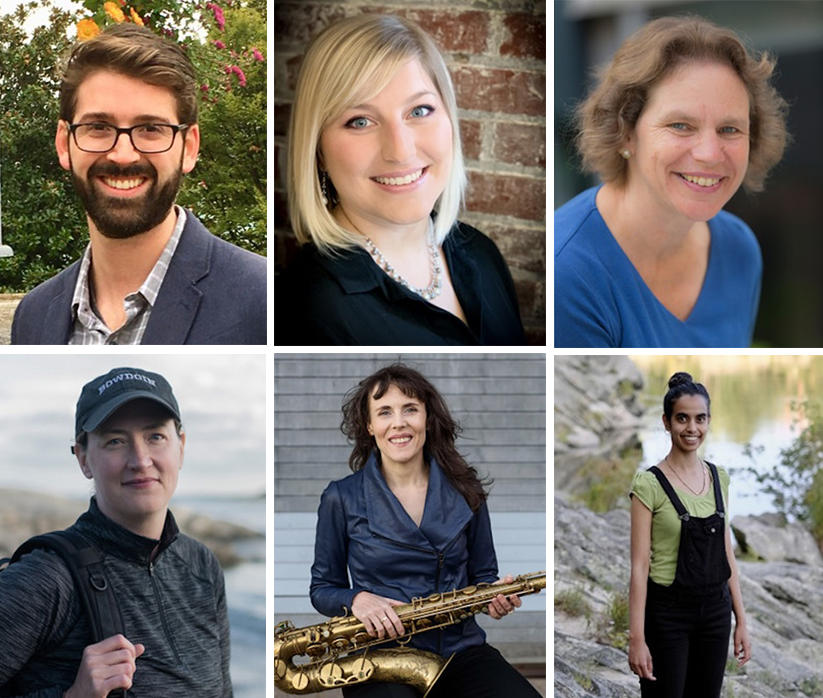

On the twentieth anniversary of the first publication of the ACE research, in 1998, Craig McEwen, an emeritus sociology professor, and Scout Gregerson ’18 are advocating for a reassessment and an update to the metric. They present their arguments in a paper that will be published this winter in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine (which first published the original research).

"We need to be critical of where we are going with ACE and be aware of its outcomes," Gregerson said. "We need to take a step back and look at how are we measuring adversity, what we mean by that, who we are including, and who we are leaving out."

To start, the original ACE metric was based on a sample of predominantly white, middle-class subjects, and evaluates their exposure to emotional, physical, and sexual abuse as children. So from the beginning, the parameters of adversity excluded the everyday experiences of people who live in racially segregated and poor communities.

Additionally, existing ACE research rarely accounts for the positive attributes of communities, such as mentoring programs and churches, which can help shield children from the worst effects of domestic violence, substance abuse, poverty, and other harmful experiences.

To remedy these shortcomings and broaden ACE's scope, McEwen and Gregerson collaborated last year to survey a wide swath of interdisciplinary research. In the field of sociology, they read the latest findings on social determinants on health, such as race, poverty, and residential location. They examined neuroscience studies on the effects of stress on young people's brain development. They caught up on the latest literature on the psychology of resilience—what promotes it and what hinders it, and they evaluated current models of trauma-informed therapeutic interventions.

Based on their findings, they argue that the specific measures of adversity in the ACE survey fall short of addressing many other experiences that heighten toxic stress for a child, such as racism, homelessness, erratic working schedules of caretakers, environmental pollutants, and neighborhood violence.

By not taking these broader social and economic circumstances into account, the ACE questionnaire and the movement it has generated tend to see families as the source of unhealthy environments for children. With such a narrow scope, the movement's backers tend to miss the many contributions of our larger social systems, according to both McEwen and Gregerson.

"The sociologist in me and in Scout says look, we as a society systematically create adversities by failing to deal with childhood poverty, to provide support for families, to have accessible, high-quality childcare, to make high quality health care widely available, to have work schedules that lead to consistent childcare," he said. "We need to take account of a much wider range of adversities, and if we did that, we'd recognize that adversities are not evenly distributed in the population."

They suggest that widening the measures of adverse childhood experiences to include broader social forces could lead to more expansive and effective therapeutic approaches. But fixing families and individuals only goes so far. Policy, too, must be changed to ensure children grow up in healthy environments with strong community supports.

"Social policy can bring about primary prevention," McEwen said. "Preventing adversities from having the effects that are problematic for childhood development takes community resources and investment, and public policy."

Gregerson reinforced McEwen. "We can't keep our responses and interventions in the medical realm," she said. "They also have to be in the social realm and political realm, because we know that is where we can make the biggest impact, where we can address the root causes of adversity."

Since graduating last May with a major in neuroscience and a minor in sociology, Gregerson has been working at Planned Parenthood in Portland, Maine, as a health care associate. Eventually, she would like to pursue graduate school in healthcare policy. She said her research project with McEwen last year reaffirmed her excitement around policy and primary prevention. "Putting it on paper, I realized, wow, this really matters," she said.