For Conscience and Country

By Nathaniel Harrison ’68 for Bowdoin MagazineON A BRIGHT AND EARLY JUNE MORNING IN 1968, halfway through one of the most tumultuous years in American history and days before I was to graduate, there came a knock on my door at what was then called the Senior Center.

It was Bill Bechtold, my fellow English major, Masque and Gown colleague, and friend. He had come to report that Robert Kennedy had been shot earlier that morning in Los Angeles. In his voice and demeanor there was a combination of fury, disgust, and disbelief.

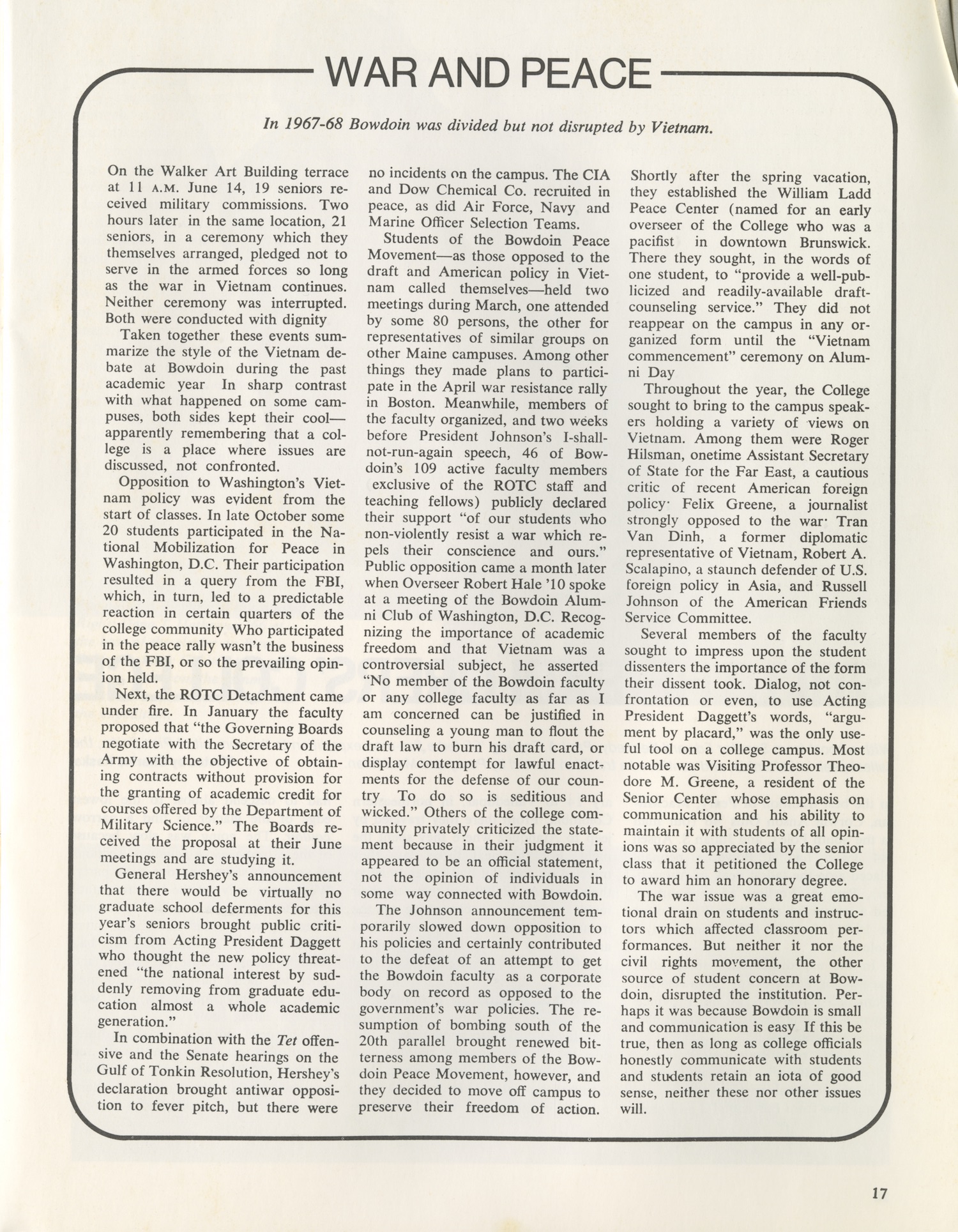

In the final six months of our college years, the peace and serenity afforded by Bowdoin’s sheltering pines had been pierced by news of carnage in Vietnam, two political assassinations, rebellions in the inner city, and a stunning upheaval in Washington.

A generation was now in open and passionate defiance of their parents’ values and convictions. With assassinations and social chaos threatening the pillars of American civilization, novelist John Updike wondered whether God had given up on the United States.

Late in the first month of 1968, the notion that the United States might effect a triumphant and honorable exit from Vietnam was brutally shattered by the Tet offensive. In one brazen attack on January 31, Communist troops seized the US Embassy in Saigon and held it for several hours. While the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong suffered staggering losses in the overall onslaught, the offensive was nonetheless a brilliant propaganda victory for Hanoi.

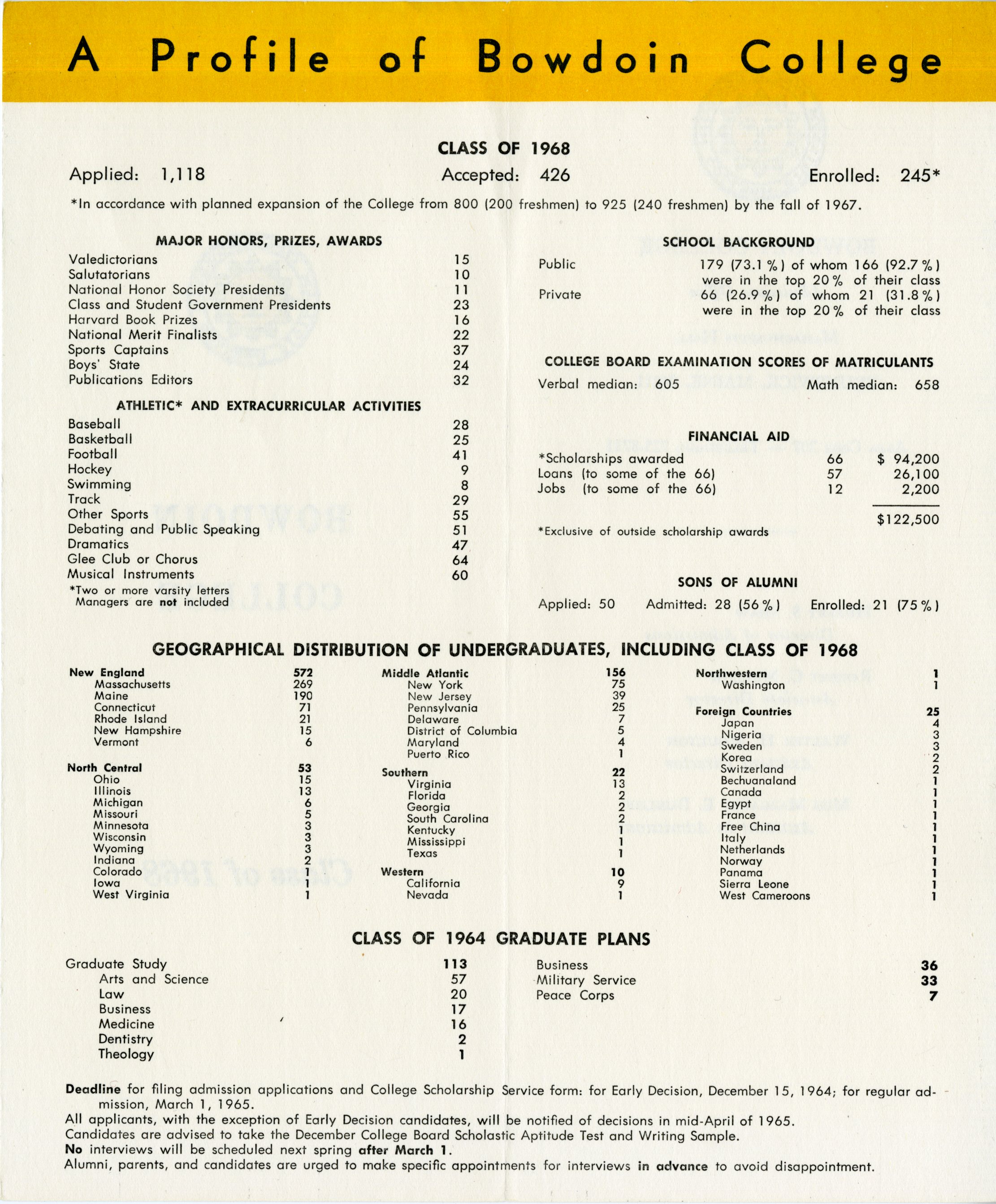

The uprising served to inspire the antiwar presidential campaign of Minnesota Senator Eugene McCarthy. In March, his legions of freshly groomed college students mobilized to secure him an improbably impressive showing in the New Hampshire primary, where he faced sitting President Lyndon Johnson—Johnson scraped by with 48 percent of the vote to McCarthy’s unexpected 42 percent.

The shock of Tet and the surge in McCarthy’s political fortunes convinced Johnson that war in Vietnam was unwinnable. And so, on March 31, he stunned the nation with an announcement that he would not be a candidate for reelection in November.

With Johnson out of the way, New York Senator Robert Kennedy, a far more passionate antiwar campaigner than the bookish, mercurial McCarthy, announced his own candidacy for the Democratic nomination.

The groundswell rolling inexorably to victory in November, and an early end to the war, was unstoppable—or so it seemed.

In April, the mayhem that Vietnam had become for US troops seemed to come home. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., who a year earlier had committed the power of his conscience and courage to opposing the war, was assassinated in Memphis. His murder ignited an explosion of outrage and violent protest in African American urban communities around the nation.

Between January and June of 1968, there were 221 significant antiwar demonstrations at 101 colleges across the country that involved nearly 40,000 students.

Bowdoin was not among them.

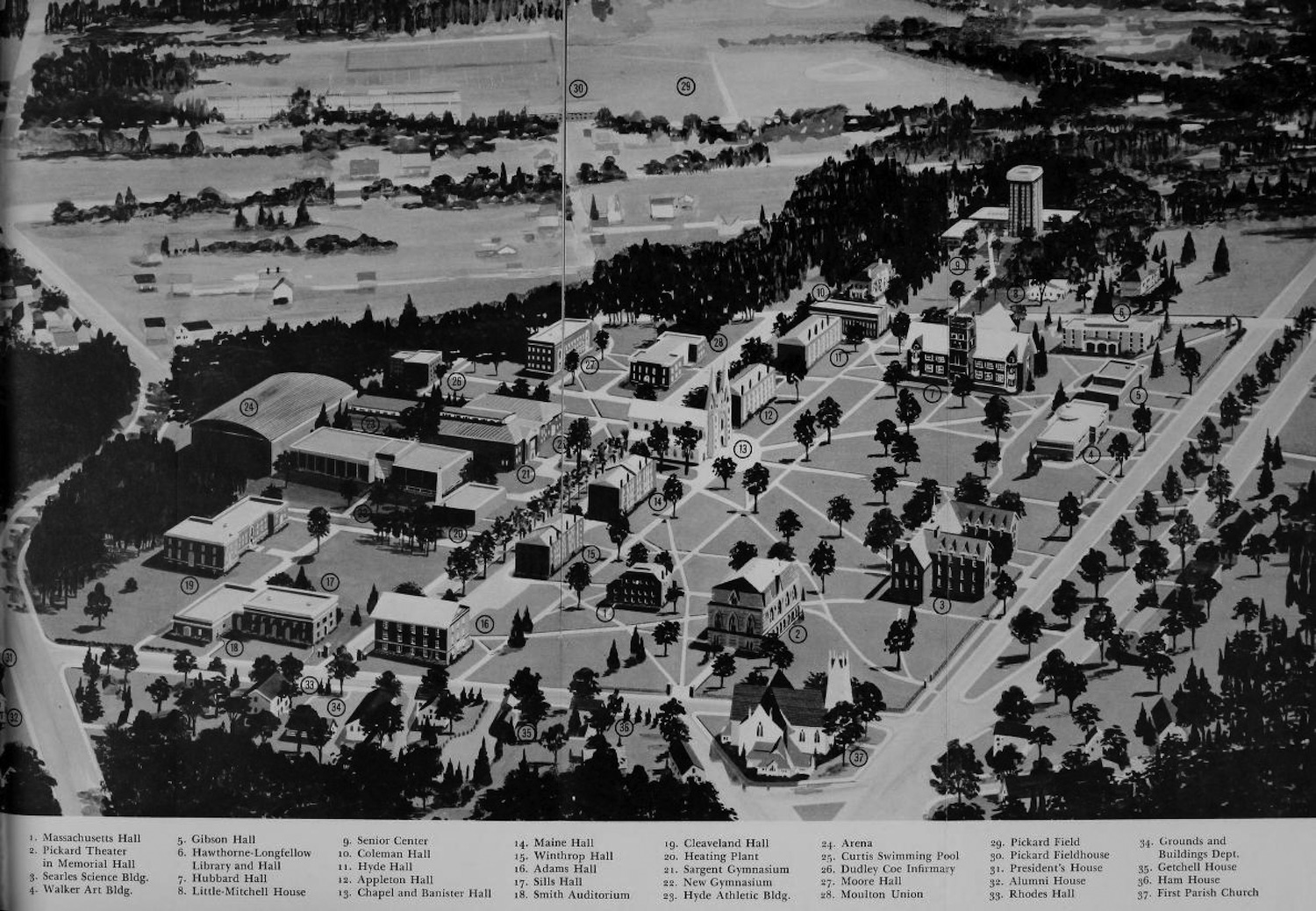

Bowdoin men at the time were not infrequently chided for being apathetic and apolitical, too consumed with planning their careers to engage with the wider world. And the antiwar movement was indeed slow to make its way up to Brunswick, but it did get there. By June 1968, Bowdoin students were engaging in weekly antiwar vigils on the Brunswick Common and attending rallies and demonstrations in Augusta, Boston, New York, and Washington.

A few days before graduation, I was among about a dozen seniors who gathered on the steps of the Walker Art Building to sign a statement vowing never to serve in the US military as long as it was at war in Vietnam.

“We were a minority on campus, but hardly a persecuted one. My encounters with classmates who defended the US campaign in Vietnam, and in several cases who were to serve there in the US military, were always civil and restrained. The Bowdoin family remained intact.”

I was an ardent supporter of the war as a freshman, but my patriotic flame began to flicker a bit sophomore year, notably with the launch of a US air campaign against North Vietnam, a nation that had done the United States no palpable harm.

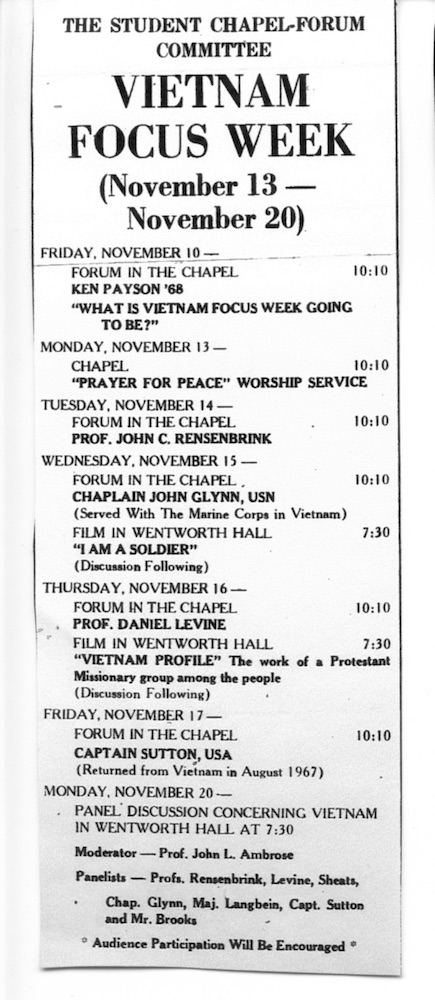

Still, it had never occurred to me that I might actively protest the war. That would change one

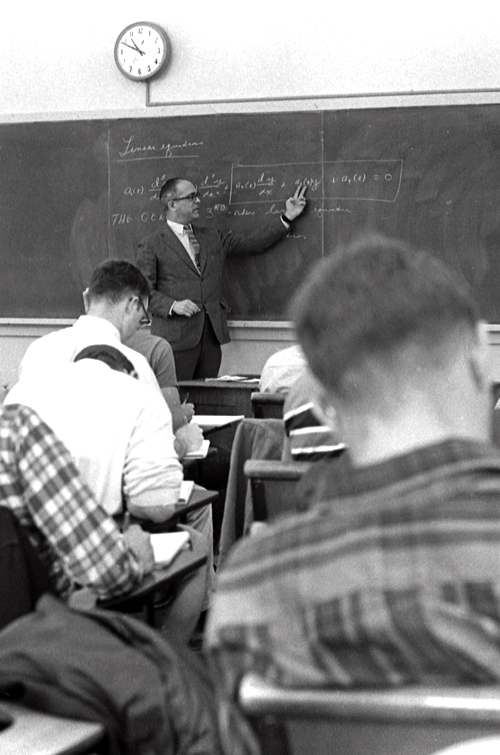

memorable night in November 1965, when I attended a talk by Professor Reginald Hannaford of the English department, a Quaker and a pacifist. I can no longer recall precisely what he said. What I can recall is the effect his words had on me—words that endowed conscientious defiance of one’s government with legitimacy and honor. Here was someone who thought and cared deeply about political morality, who was struggling to resolve the question of where a man’s duty lay—to his conscience or his country.

It was a life-changing moment.

Hovering ominously over anxious late-night conversations in the Moulton Union cafeteria or at Bill’s, a favorite downtown Brunswick watering hole, were the draft and the war and the frightening decisions we would have to make: to obey and serve or defy and resist—or perhaps dodge. Graduate school deferments were not assured, and so options were stark and few: enlistment in the regular forces or the National Guard, escape to Canada, conscientious objection, the Peace Corps perhaps, or underground resistance and a possible federal prison sentence.

I made my choice, and it was from a village in Senegal, as a member of the Peace Corps, that I followed the momentous events of the final six months of 1968, when hopes for decisive action to end the war were dashed. In August, at the close of a convention in Chicago that produced horrifying images of police assaulting demonstrators, Vice President Hubert Humphrey won the Democratic Party presidential nomination.

My classmates and I shared difficult decisions and a senior year of great turmoil, but our stories are each uniquely our own.

On the occasion of our fiftieth reunion from Bowdoin, some of them shared theirs with me:

Richard Berry

Anthony Buxton

Chester Freeman

Carroy Ferguson

Rick Read

Michael Rice

Jeff Richards

Gary Roberts

Of further interest, the late Dave Doughty '68 maintained two blogs, one about the Class of 1968 in general, and one about classmates' experiences in Vietnam.

This story first appears in the Fall 2018 issue of Bowdoin Magazine.

Update your mailing and subscription information, and browse other features and profiles here.