Bowdoin Senior Follows 63-year-old Art History Trail to Hiroshima

By Rebecca Goldfine

The four artists are all elderly now, all still living in Hiroshima. Last summer, a Bowdoin student visited them to talk about drawings they had made as children six decades before in 1953 — about eight years after the US dropped nuclear bombs on their city.

Revisiting their childhood paintings prompted the four to share difficult memories of the years following the carnage. They offered their reflections on war, struggle, peace, and survival. And, perhaps a bit surprisingly, they smiled a lot as they looked at their pictures.

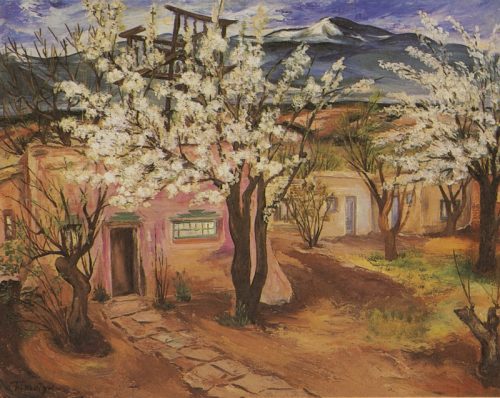

Chuzo Tamotzu (1888-1975)

Bowdoin’s Michael Amano ’17 had a Curatorial Fellowship from the Bowdoin College Museum of Art to spend last summer in Japan tracking down and interviewing some of the people who had participated in a 1952-1953 art exchange between Japanese and US schoolchildren. Hundreds of students submitted pictures to this exchange — specifically between the cities of Santa Fe, New Mexico, and Hiroshima. The project was organized by Chuzo Tamotzu, a Japanese-American artist living in Santa Fe.

While almost half of the Japanese drawings have been preserved, the Bowdoin Museum of Art has not yet been able to find a single drawing by an American student, said Anne Collins Goodyear, co-curator of the Museum of Art. However, she added she is “cautiously optimistic” that the American drawings will be recovered in Hiroshima after a bit more digging.

Meanwhile, the Museum of Art has on loan 44 of the original 100 or so Japanese drawings. They are on display now at the Museum’s exhibition “Perspectives from Postwar Hiroshima: Chuzo Tamotzu, Children’s Drawings, and the Art of Resolution.” Others pictures were sold in auctions during the 1970s to support the healthcare needs of atomic bomb survivors living in the United States.

The reason so many Japanese pictures were saved was because they ended up with Tamotzu’s niece, Barbara Kates-Garnick. She and her husband, Marc Garnick ’68, took special care of the collection. It’s possible someone in Hiroshima has done the same with the American drawings.

Despite Tamotzu being an accomplished painter and printmaker, he was reportedly most proud of his children’s art project, Goodyear said. “Chuzo was a major proponent of young people, and he felt in the wake of WWII…that children and young people had a special role to play in helping heal wounds and to building bridges that would ensure future peace.”

At a recently gallery talk, Amano described his encounters with four of the Hiroshima artists. “A lot of them [told me] how difficult it was for their parents to find food and shelter” after the bombs fell, he recounted. “They went to schools in shells of concrete buildings.” One spoke about seeing classmates with keloid scarring.

Yet, the children’s drawings don’t depict pain or suffering. They are filled with scenes of school plays, nature, and city streets. “I wondered why a child would choose to draw these kind of images where you don’t see any evidence of trauma, even though they are growing up in a city devastated by an atomic bomb,” Amano shared.

The students may have been instructed by teachers to only paint certain subjects, or focus on specific themes, Amano suggested. Whether or not they worked under restrictions, he sees in all of them a kind of hopefulness that is universal to children. “There is a sense of idealism and universality that emerges from them, like in all of the children’s art I have seen, and used to make myself,” he said.

With help from some Bowdoin professors who have contacts in Japan, Amano was able to locate and get in touch with the four artists. His most helpful connection was with a reporter at a regional newspaper. When she put out a list of the names of all the Japanese people who had submitted art back in 1953, her phone quickly started to ring.

Amano, who studies neuroscience and Asian Studies, and whose grandmother is from Hiroshima, interviewed three men and one woman: Kiyoshi Hayashi, Shoji Noma, Masaharu Takami, and Taiko Terakawa. The artists told the college student about their lives and what they thought was going on in their drawings (none of them actually remembered making them). When Amano asked them what they would like to convey to people who see their drawings today, they shared these messages:

Taiko Terakawa

“When people think about Hiroshima Prefecture, and think about it as a place of an atomic bomb, rather than sympathizing, I want you to meditate on the city’s history and write it on your hearts. I hope this will bring people together with the goal of world peace.”

Shoji Noma

“There was no food after the war. People worked their hardest to make it through those times. In addition to food, they starved for entertainment, too. I think I drew this [a scene from a folktale about a bear] because it made me happy. Even now, it still does.”

Masaharu Takami, owner of a Mazda dealership

“Art, or rather a picture like this, is something that allows you to remember your life. Even more than that, it’s something that can bring you lots of happiness.”

Kiyoshi Hayashi, former electrical engineer for Hiroshima

“To live among nature is the best. And when I say nature, I mean greenery. To be surrounded by it is the most important thing. When you come to a place with greenery, you can tell there is no war being waged there.”

Amano notes how many of the Japanese students’ drawings are filled with greenery. After the atomic bombs destroyed Hiroshima, the city lost much of its vegetation. Many thought it might not grow back for 75 years. The few trees left standing are protected today as special landmarks. But after the rubble had been cleared, vegetation did begin to come back, and abundantly, growing everywhere in a city largely free of obstructing infrastructure.