Whispering Pines: 'Those Who Do the World's Work'

By John Cross '76

Earlier this month, as Hurricane Matthew left a path of destruction across Haiti and eastern Cuba and threatened the Atlantic coast of Florida, Georgia, and the Carolinas, US Coast Guard personnel prepared for the worst, tracking the hurricane, warning residents, preparing for search and rescue missions by air and water, and coordinating efforts with local and state officials.

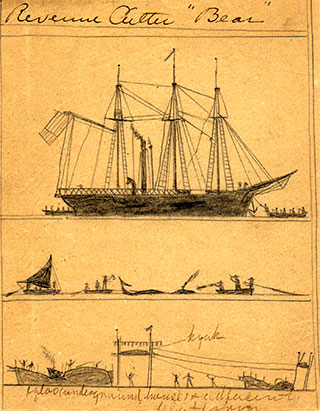

The US Coast Guard traces its roots to the Revenue Marine Service, established in 1790 on the recommendation of Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton to provide armed enforcement of the nation’s customs laws. Although the Treasury Department oversaw the service throughout the nineteenth century, captains of Revenue cutters reported to local customs officials. After the Civil War it became apparent that the Revenue Marine Division was an inefficient operation. Politically-appointed customs officers could (and sometimes did) appoint captains of Revenue cutters who had never been on a ship; in some cases, customs officials used the cutters as their private yachts.

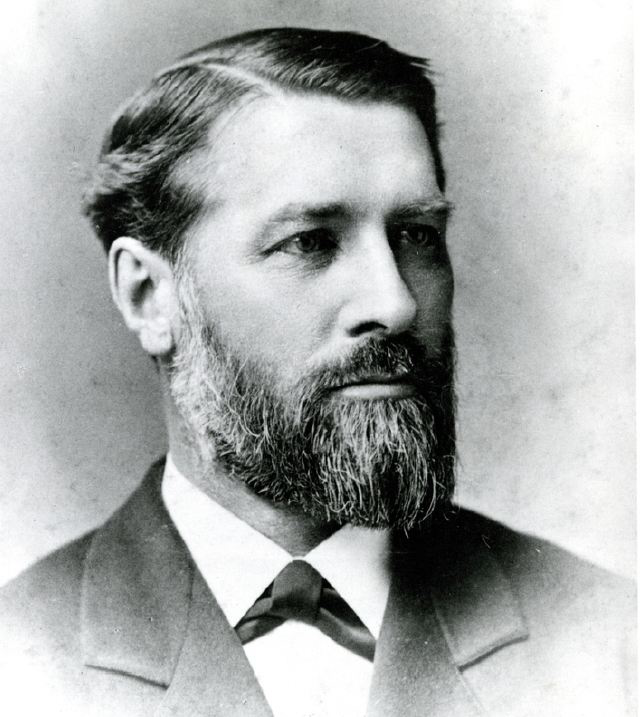

In 1871 the Grant administration turned to an able civil servant and efficiency expert in the Auditor’s Office in the Treasury Department to deal with the “unsatisfactory condition” of the Revenue Marine Service. In the face of substantial political headwinds, Sumner Increase Kimball of the Bowdoin Class of 1855 quickly established fiscal and administrative discipline as chief of the division. He insisted that all hiring and promotion be based solely on ability and merit, and he ended perks and opportunities for nepotism by taking control of the Revenue cutters from customs officers. He slashed budgets, overhauled the Service’s administrative structure, and established standards for training and operation. During his tenure as chief of the Revenue Marine Division (1871-1878), Sumner Kimball also established the Revenue Marine School of Instruction in 1876 in New Bedford, Massachusetts, to provide practical and academic training for cadets.

Kimball was born in the southwestern Maine town of Lebanon and grew up in nearby Sanford. He taught school and clerked during vacations to pay for college. After graduation he studied law, was a commission clerk in the Maine Secretary of State’s Office, and was elected as the youngest member of the Maine House of Representatives, where he chaired the Judiciary Committee. In 1860 he began as a clerk in the Treasury Department in Washington, and as the department grew in size from twenty-one employees to more than 500 by the end of the Civil War, Kimball’s abilities as an effective and efficient administrator attracted the attention of the Secretary of the Treasury.

Kimball lobbied a tight-fisted Congress to put the money saved by his efficiency measures into what was at the time a poorly-equipped system of rescue stations scattered along the New Jersey coast and manned by volunteers. By an act of Congress of June 18, 1878, the US Life-Saving Service was established as a distinct bureau, with Sumner Kimball as Superintendent. He immediately brought his skills and energy to bear on the problem. He personally inspected sites for new life-saving stations along the Atlantic, Gulf, and Pacific coasts, the shores of the Great Lakes, and even the station at Louisville, Kentucky, to protect lives and shipping near a dangerous stretch of the Ohio River. The full-time crews of the US Life-Saving Service were hired for their fitness for the job, whether it was walking the shore on a night watch in all kinds of weather or bending over the oar of a heavy surfboat as it plowed through breakers. Kimball insisted on the highest standards for training on the latest equipment for ship-to-shore and at-sea rescues. In the first year that his system was in place, there were no lives lost to shipwreck. The US Life-Saving Service became one of the government’s most successful and popular agencies.

For many years Superintendent Kimball continued to advocate for better pay and for some kind of a retirement plan for long-serving members of the Life-Saving Service, arguing that the work was strenuous and dangerous, that crews had to buy their own foul-weather gear, and that the daily allowance for food (30 cents) was inadequate. In 1915 Kimball’s goal was realized by the passage of a bill to merge the Revenue Cutter Service and the US Life-Saving Service to form the US Coast Guard, with the training school that he had founded becoming the US Coast Guard Academy. He retired at the age of 81, having served eleven presidential administrations, from Grant’s to Wilson’s.

Sumner I. Kimball’s remarkable achievements intersected with the lives of two other alumni, whose own records are worthy of note. Kimball’s Revenue Marine School of Instruction called for training cadets in practical matters such as setting sails, navigation, and gunnery. A second component was academic instruction, and for that he turned to Edwin Emery of the Bowdoin Class of 1861.

Emery, a Sanford native, was a member of Phi Beta Kappa and was the pitcher in the first baseball game played at Bowdoin in September of 1860. He joined the 17th Maine Infantry Regiment as a substitute for a friend, and kept a five-volume diary of his experiences during the war. He was badly wounded at Spotsylvania and lay on the wet ground between the opposing lines for twenty-four hours before being rescued. His roommate of three years at Bowdoin, Captain William Morrell of the 20th Maine, was killed several days earlier on the same field of battle.

Upon returning from the war, Emery embarked on a career as a teacher and school principal. While he was teaching in Southbridge, Massachusetts, he encountered an energetic and rambunctious boy who tested (but never exceeded) the limits of Emery’s patience. Years later, Billy Hyde—now President William DeWitt Hyde—reflected on the many lessons he had learned from Principal Emery. He may have been required to draw on those lessons when Edwin’s son, William Morrell Emery (named for Edwin’s Bowdoin roommate) arrived on campus with the Class of 1889.

In 1877 Edwin Emery accepted an appointment as the sole member of the academic faculty at the Revenue Marine School of Instruction. For the next thirteen years he taught the entire academic curriculum: arithmetic, algebra, trigonometry, geometry, astronomy, French, English composition, rhetoric and correspondence, physics, theoretical steam engineering, world history, US history, international law, constitutional law, and marine law. When President Benjamin Harrison gave in to pressure to have Revenue Service training take place at the Naval Academy in 1890, Emery went into the insurance business in New Bedford, and spent his last years writing a history of his home town of Sanford. In recognition of his role in the creation of the training school, a new annex was named for Edwin Emery at the Coast Guard Academy in 2011.

Another Civil War veteran from the Maine town of Limerick figures into the narrative set in motion by Sumner Kimball. Horace L. Piper entered Bowdoin with the Class of 1863, but left to join the 27th Maine during the war. The regiment was assigned picket duty around Washington for the entire nine-month term of enlistment. In a fascinating footnote to history, all 864 members of the regiment—including Major Piper—received Congressional Medals of Honor on the order of Secretary of War Edwin Stanton because 309 (or 312) members of the regiment volunteered to stay and protect Washington after other Union troops had been drawn away in the summer of 1863 to confront Robert E. Lee’s army in Pennsylvania. In 1917 the medals were rescinded by the government, but that’s a story best told in A Shower of Stars by the late John J. Pullen H’58.

Instead of returning to Bowdoin after the war, Piper earned a law degree from Columbian University (now George Washington University), and then entered the civil service in the Auditor’s Office. In 1890 Kimball invited him to become the assistant superintendent of the US Life-Saving Service. From that date until his death in 1905, Piper was a popular public speaker on the mission and activities of the service. By a provision of his will, Sumner Kimball established the Horace Lord Piper Prize at Bowdoin, which is awarded to that member of the sophomore class who presents the best “original paper on the subject calculated to promote the attainment and maintenance of peace throughout the world, or on some other subject devoted to the welfare of humanity.”

Sumner Increase Kimball shrugged off the accolades that came his way, saying in response to President Woodrow Wilson’s effusive letter of praise, “I may have earned some credit. I do not deserve all the encomium he has heaped upon me.” Bowdoin awarded him the honorary degree of Doctor of Science in 1891. Kimball’s will provided for a prize in his own name at Bowdoin, to be given to that member of the senior class who has “shown the most ability and originality in the field of the Natural Sciences.” He would have appreciated knowing that the Sumner I. Kimball Readiness Award is the highest honor that a Coast Guard unit can receive. The merchant ship Sumner I. Kimball was sunk off the coast of Newfoundland by a German submarine in January of 1944, but his name lives on in the Kimball, a state-of-the-art National Security Cutter being built for the Coast Guard, with a launch date set for 2018.

There is perhaps no better way to conclude this column than to quote Kimball himself: “Here and there may be found men [and women] in all walks of life who neither wonder nor care how much or how little the world thinks of them. They pursue life’s pathway, doing their appointed tasks, without ostentation, loving their work for the work’s sake, content to live and do in the present rather than look for the uncertain rewards of the future. To them notoriety, distinction, or even fame, acts neither as a spur nor a check to endeavor, yet they are among the foremost of those who do the world’s work.”

With best wishes,

John R. Cross ’76

Secretary of Development and College Relations