Collaborative Initiative Studies How to Aid Recovery of Maine’s Coastal Fisheries

By Tom Porter

Collaborating in the project are Bates College, the University of Southern Maine, and the Penobscot East Resource Center. Apart from Lichter, the other Bowdoin faculty members involved are Phil Camill from the Department of Earth and Oceanographic Science, Environmental Studies Lecturer and Program Manager Eileen Johnson, Associate Professor of Economics Guillermo Herrera, and Coastal Studies Scholar Ted Ames of the Penobscot East Resource Center. The project was funded by a National Science Foundation grant that is part of the Sustainability Solutions Initiative, a statewide initiative organized by the University of Maine at Orono to encourage collaborative research between institutions aimed at meeting “human needs while preserving the planet’s life support systems.”

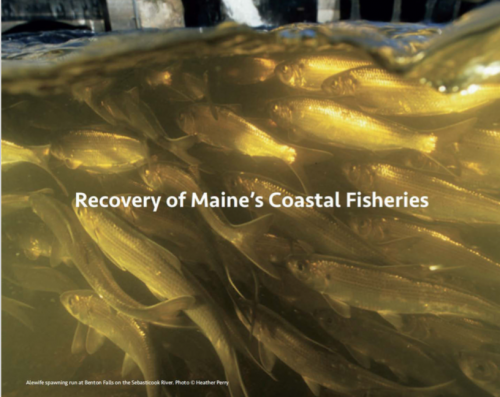

The result is a colorful and informative 24-page publication titled “Recovery of Maine’s Coastal Fisheries.” Lichter described it as an “outreach booklet” and he was keen to point out that this is not an official peer-reviewed study. “It’s meant to be part of an ongoing effort to inform the public about what’s possible in terms of the ecological recovery of fisheries. We’ve also produced a short video to go with the booklet.” Click here to watch the video.

Over-reliance on lobster

The concern that underscores this project, said Lichter, is the current over-reliance of Maine’s marine economy on one species-lobster. “Commercial fishing in the Gulf of Maine was very different sixty years ago,” he said. “Apart from shellfish, a variety of organisms were harvested: probably six to eight species, including groundfish like cod, pollock, and haddock.” It would be economically prudent, he added, for Maine’s fishing industry to shift from its narrow focus on lobster to a diverse set of target species like those commonly harvested sixty years ago. Although the lobster population remains healthy in the Gulf of Maine at the moment, the booklet warns there is a “significant probability that high lobster densities coupled with warming waters will result in a catastrophic decline in lobster numbers sometime in the future.” As an example it points to the collapse of the lobster fishery in Long Island about fifteen years ago, affected by warming waters and disease.

So how did Maine become so reliant on one species? And, by extension, what caused groundfish to effectively disappear from the state’s coastal waters over the last few decades? Human activity plays a big part, said Lichter, “but it’s not just overfishing. We also undermined the marine food web by building dams on rivers, something which impacted the sea run fish that groundfish fed on by preventing them from getting upriver to spawn. The loss of habitat, such as eelgrass, may also be a key factor,” he said, “as it provides an important haven for a number of marine species.”

Successful restoration efforts

On the plus side, the battle for recovery has already begun and a number of restoration efforts are underway. The booklet points to the success of dam removal and fish passage initiatives on a number of Maine rivers, which when combined with the environmental cleanup that’s been going over the last few decades, has resulted in a notable rebound in numbers. For example, in the Kennebec river system, alewife and blueback herring populations are up around 4,000 percent in the last eight years, “with as many as two to three million adult fish returning to spawn annually.”

This modeling is hard to do, said Herrera, because of all the unknowns out there. But, he added, even without a groundfish resurgence, the restoration of the sea-run fish themselves yields economic and ecological benefits. “Forage fish have value as a harvested stock, primarily as lobster bait.” They also help restore coastal areas to their natural ecology and attract avian predators, he explained. All of which brings an indirect economic impact to the area in terms of tourism dollars and property prices, although the precise value is hard to quantify.

Using historic data

To understand the importance to groundfish of sea-run fish like alewives, the project builds upon the decades of work done by long-time commercial fisherman and fisheries ecologist Ted Ames. As well as being a former visiting coastal studies scholar at Bowdoin, Ames is also co-founder of the Penobscot East Resource Center in Stonington, and the winner of a MacArthur fellowship in 2005. To reconstruct a history of the Gulf of Maine fisheries, Ames interviewed a lot of fishermen. “The MacArthur publication,” he said, “not only tracked the demise of marine and sea-run fisheries, but identified a process for restoration.”

Working with Ames, Eileen Johnson did a lot of historical research, “going back and looking at what systems were like in the early 1900s.” She worked with Andy Bell ’11, Catherine Johnston ’12, Corey Elowe ’11, Elsie Thompson ’11, Min Lee ’14, and Nora Hefner ‘16 to map out historical alewife runs in order to analyze their correlation with cod landings. It’s something which Johnson said helps stakeholders understand the impact that the construction of hydro-electric dams had in Maine in the mid-twentieth-century.

The path forward

This booklet, and the ongoing work being done as part of the Sustainability Solutions Initiative, recognize that there is still some way to go to re-establish a diverse and well-populated ecosystem in the Gulf of Maine. Although the researchers will be publishing their results in academic journals, what sets this publication apart is that it was written specifically to make research findings more accessible to stakeholders. A large component of the overall research project was engaging stakeholders throughout the process and understanding ways that scientific findings could be communicated in ways to better inform policy-making. For example, said Johnson: “As part of our research, we interviewed stakeholders to learn more about how they access and use scientific findings in decision making. Having the data out there,” she said, “helps people think about how we could be moving forward.” The collaboration was also important, she added, in getting people to think about individual river systems as part of a much larger picture.

“These are exciting times to be involved in initiatives likes this in Maine,” said Herrera, “because a lot of dams are being re-evaluated as they come up for re-licensing by federal authorities, and I think there’s an increasing awareness of the benefits of having a river restored to its natural state, versus the economic arguments of keeping the dam in place.” Although this work does not readily provide concrete numerical answers, he said, “it does give an important sense of what those trade-offs are, and will hopefully lead to more informed policy decisions.”

The fish lift at Benton Falls dam