Prof. Riley: Making Sense of China's One-Child Policy

By Rebecca Goldfine

Since China abolished its one-child policy last fall, many commentators have weighed in on the policy, debating its merits and impacts. Professor of Sociology Nancy Riley has studied China’s population issues for many years and has published widely on subject. Her forthcoming book, potentially titled Population and Policy in Contemporary China, will come out later this year with Polity Press.

This week she spoke to Bowdoin faculty about the one-child policy, its history and its consequences. Below are some of the salient points Riley made. They have been lightly edited.

The universality of population policies, even in the U.S.

“It is important to remember that the state influences population policies in almost every country. In China the state involvement was direct, obvious and sometimes heavy-handed, but the government in the United States is also influencing population. The fact that we haven’t had good healthcare influences mortality rates, and the lack of good public support for childcare or for working parents influences fertility.”

The one-child policy’s beginnings

“When the policy was established in 1980, China had a planned economy. Production and consumption were both planned and controlled by the state, and population was part of state planning. A few reproduction policies preceded the one-child policy, but the one passed in 1980 was the most important. It stipulated that every couple would have one child and that the timing of that child, when the child would be born, would be controlled by the state.”

Why the policy was implemented

“Some of it was about balancing grain production and population. The government wanted balance so everyone in China could be fed properly. The government was also looking ahead and focusing on its modernization projects. China wanted to modernize economically, and at that time, many demographers inside and outside of China believed that economic growth would actually lead to fertility decline. So Chinese leaders thought, ‘Well if that’s true, perhaps we could flip that. If we cause fertility to decline, perhaps that will help our economic growth.'”

How the policy was implemented

“The numbers of births allowed at any given year was established at the central level in Beijing and those population goals were filtered down to the provincial level and further down to the counties, the cities and the communes, and further down still, to the lowest levels, the production teams. The production teams in a province would get permission to have, for example, two births, and two couples would be given permission to have a birth that year. The person in charge of enforcing this at the local level was part of the village. These birth planning workers were very key, they were the agents of the state, and they were the local enforcers of this population policy.”

Enforcement

“Enforcement took a variety of means in both rural and urban areas. In general the major tactic used in birth planning was education and persuasion. Another way the policy was enforced was access to contraception and abortion; contraception was free and abortion was on demand. Positive incentives included offering better jobs, higher pay or good schooling to parents who agreed to have only one child or agreed to be sterilized. Negative sanctions, which occasionally could be severe, included fines, docked pay, barring children from school, razed homes or forced abortions.”

Outcomes

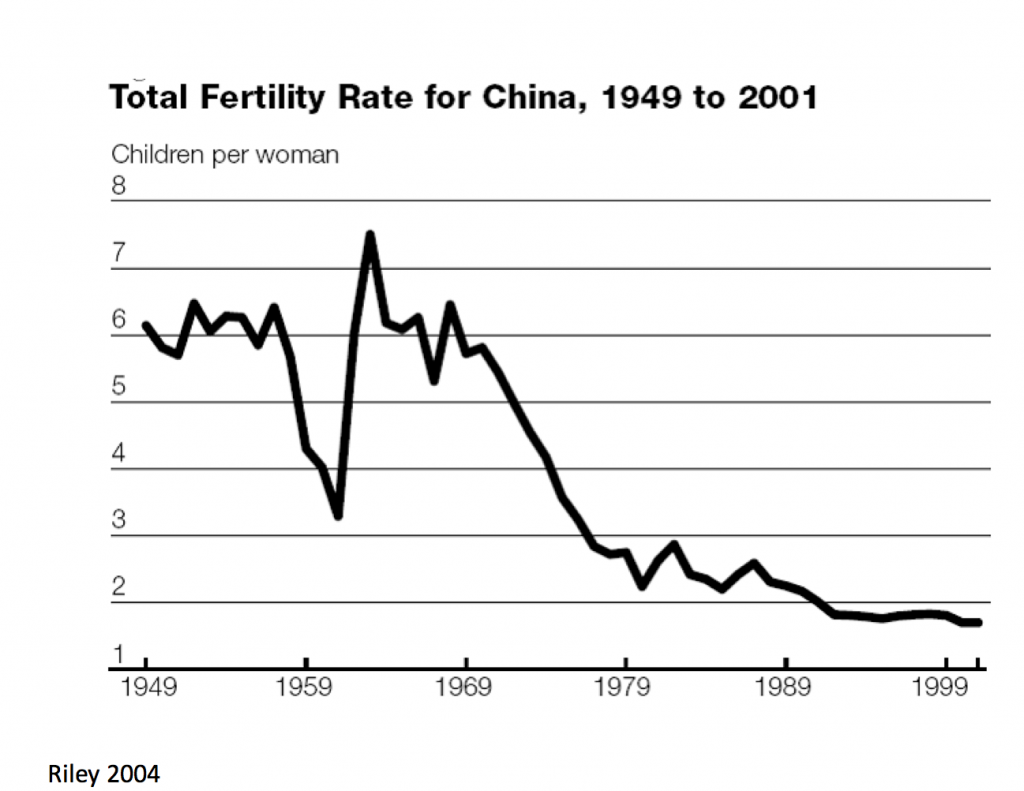

“The state created a massive system from the top to the bottom of the society to achieve a goal of fertility reduction and population control. And it was in many ways successful in persuading citizens that small families were necessary for the country to achieve economic success. Most people in China believed that population control was the purview of the state, the state should plan population as it planned the economy. The birthrate declined from an average of six children per family in the 1940s to about 1.5 per family today.

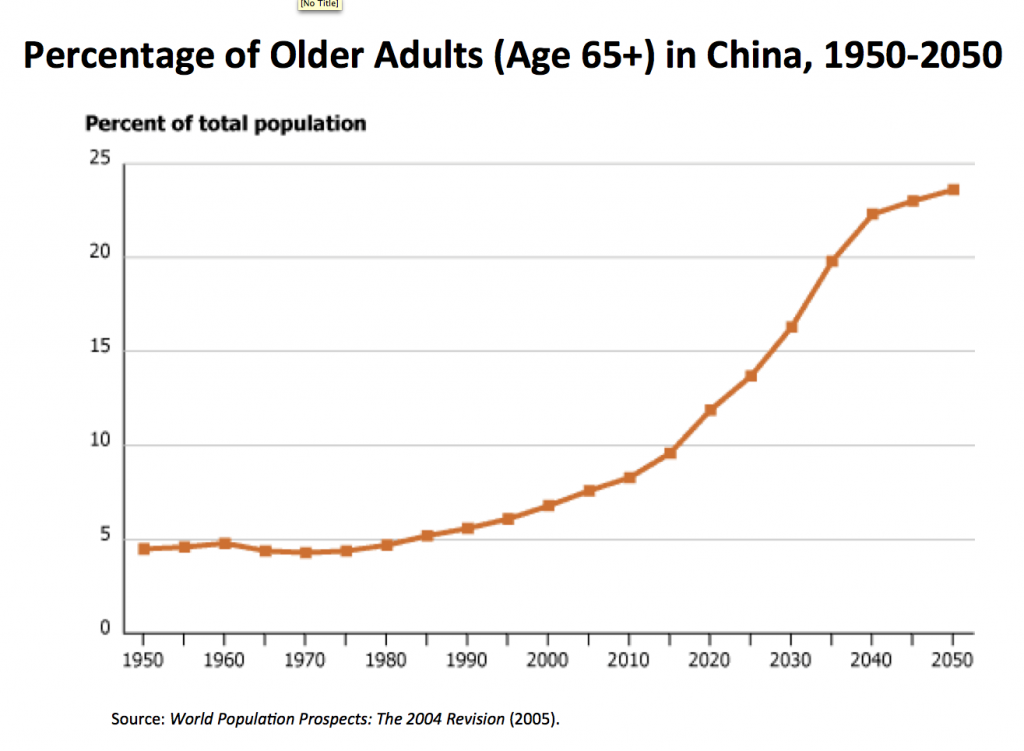

One of the arguments people have made is that China didn’t need a birth planning policy because fertility began to fall before the policy went into effect. Another argument that people make is the aging of China’s population and how the one-child policy has contributed to that.”

Where did the girls go?

“Missing girls” refers to the girls who should have been born but were never born or who were born and died shortly after birth. The measurement of missing girls is the sex ratio at birth; the normal sex ratio of birth is 105 boys or more for every 100 girls in a normal population with no interference. China has an enormously abnormal sex ratio at birth. From 1980, the sex ratio at birth rose to 120 or 122 boys to 100 girls at its peak. That means millions and millions and millions of girls are missing in China, and have been since 1980. [However] China is not the only place that has high sex ratios at birth: Vietnam, India (where the sex ratio appears to be increasing) and Korea (until recently). None of these places had birth planning policies.”

Valuable sons in China

“People do this because they want sons, they prefer sons, they need sons. Sons do a lot of things. The family line is traced through males in China. Sons live with their parents after marriage, they are economically supportive of parents both right up to marriage and when parents are retired.”

How the government failed to save girls

“They could have said, ‘This is wrong, we don’t want our girls to go missing. So we’re going to stop the one-child policy.’ Or they could have said, ‘How do we make girls as invaluable to parents as boys?’ And there were things they could have done. They could have prevented discrimination against girls in schooling, or discrimination against women in jobs, income, or land disputes. They could have provided pensions for parents in rural areas. But the government didn’t do that.”

Did the policy help the world? The environment?

“China’s population was huge, and reducing population growth in such a huge country has had an enormous impact on the population of the world. A smaller population could lessen the burden on the environment and on its resources, but here it is not clear what changes China’s population policy has had or will have on the environment. Chinese leaders thought that a lower birth rate would make it easier for the country to modernize. And with modernization often comes more resource use, not less. Fewer children doesn’t necessarily mean fewer resources being used. So we don’t know if the reduction of population growth in China is going to have an obvious impact on the environment.”