Whispering Pines: The Medical School of Maine, Liberia, and the American Civil War

By Matt O'Donnell In his latest column, John Cross ’76 reminds us that throughout history “Bowdoin people are everywhere.”

In his latest column, John Cross ’76 reminds us that throughout history “Bowdoin people are everywhere.”

Maine joined the Union in 1820 as a free state to counterbalance the future admission of Missouri in 1821 as a state where slavery would be allowed. As one of its first actions, Maine’s first legislature voted to establish a medical school at Bowdoin College. In the spring of 1821 Dr. Nathan Smith, the founder of the Dartmouth Medical School and a professor at Yale, offered a series of lectures on medicine in Massachusetts Hall at Bowdoin. Over the course of the next hundred years the Medical School of Maine trained more than 2,000 doctors. In 1921, after unsuccessfully attempting to secure sufficient endowment to meet new standards for facilities and equipment for medical education, and in the absence of a nearby hospital for training students, the Governing Boards decided to close the medical school.

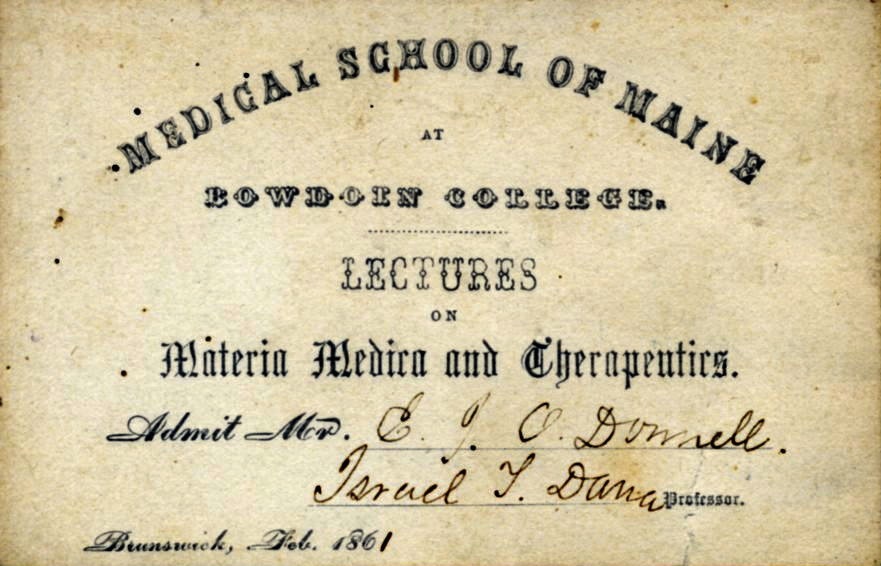

Enrollment at the medical school in the 19th century was controlled by the medical faculty (overlapping with ““ but not the same as ““ the “academical faculty”). Students received written permission to attend a series of lectures on medical topics, spread over two 2 ½ -month terms in the spring semester. Many newly-minted alumni attended the medical lectures, but did not complete the requirements for a medical degree, including Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and John Brown Russwurm. Russwurm may have been one of the first African-Americans to enroll in a medical school in the U.S. (in 1827).

A recent book by historian Winston James, The Struggles of John Brown Russwurm (2010), follows Russwurm’s remarkable life, from his birth in Jamaica to his education in Montreal and in Maine; from Bowdoin College to New York, where he co-edited Freedom’s Journal, an abolitionist newspaper; and eventually to Liberia, where he was superintendent of schools, edited a newspaper, and served as Governor of the Maryland Colony of Liberia from 1836 until his death in 1851. The book follows Russwurm’s evolving perspective on the resettlement of free blacks in Africa, from his initial strong opposition to his leadership role in the movement a few years later. At the time, and viewed through the lens of historical distance, Russwurm’s change of heart has been the subject of criticism and debate. It may have been that Russwurm was discouraged about the lack of progress in race relations in America and a future that promised only more of the same. He traveled to Liberia in 1831 and was befriended there by the first Governor of the Maryland Colony, James Hall, a New Hampshire doctor who had graduated from the Medical School of Maine in 1822. Hall remained a mentor and close friend, and Russwurm’s second child was named James Hall Russwurm in the doctor’s honor.

It was during Russwurm’s tenure as governor that the Medical School of Maine awarded M.D. degrees to John Van Surly DeGrasse and Thomas Joiner White in 1849. They were the second and third African Americans to graduate from an American medical school. Two other African Americans attended lectures at the medical school, William Miller Dutton in 1847-48 and Peter Ray in 1848, both of whom were from New York. Ray went on to receive an M.D. from Castleton Medical College and was a physician in Brooklyn for many years. It is likely that letters from Hall, Russwurm, and the American Colonization Society were instrumental in securing admission for DeGrasse, White, Dutton, and Ray to the medical school, with the expectation that upon completion of their studies, some (or all) of them would fill a critical need for doctors in Liberia. As it turns out, none of the four made that journey. The Medical School of Maine was not alone in responding to the American Colonization Society’s requests; the Harvard Medical School admitted three African Americans through the Society’s sponsorship in 1850, although these students were dismissed after tumultuous protests by the other medical students.

John Van Surly DeGrasse’s grandfather was the adopted son of French Admiral Francois Joseph Paul De Grasse. Before coming to Bowdoin, John had studied in France and trained in medicine in New York. He opened a medical practice in Boston, and in 1854 he was elected to the Massachusetts Medical Society as the first African American to belong to a medical association in that state. He was nominated by Massachusetts Governor John Andrew [Class of 1837] for an officer’s commission during the Civil War, and was appointed assistant surgeon with the 35th U.S. Colored Infantry. His commanding officer was Colonel James Beecher, the half-brother of Harriet Beecher Stowe. DeGrasse was brought up on charges of drunkenness and conduct unbecoming an officer, and in 1864 was dismissed from the Army. The evidence and circumstances, as reviewed by several historians, support the conclusion that the charges may have been false, the exaggerations of an unhappy subordinate (white) medical officer. DeGrasse returned to Boston and died of tuberculosis in 1868.

Much less is known about the life of Thomas Joiner White. He initially practiced medicine in New York after leaving Bowdoin. Following his marriage in 1856 he moved to Ontario. White died of cholera in 1863 as he was returning to the United States to join the Union war effort.

In the years immediately before the outbreak of the American Civil War, two Liberian citizens received degrees from the Medical College of Maine. Jacob Manfred Moore M’1858 had emigrated to Liberia from Baltimore with his family in 1851 at the age of 16. William H. Ealbeck M’1860 was born in Liberia, and he often spoke at meetings of the American Colonization Society in the years he was completing his medical education at Yale and Bowdoin. After the war, Liberian-born John Naustedla Lewis M’1872 received an M.D. from Dartmouth. All three became physicians and prominent citizens back in Liberia.

I’ve managed to convince myself as I write this that there are some common threads that run through the disparate parts of this narrative. The American experience with slavery echoes throughout the story ““ in the Missouri Compromise that brought Maine statehood and established the Medical College of Maine, in the mixed motivations behind repatriation of free blacks to Africa, in the accessibility of medical training, and in the causes, conduct, and consequences of the American Civil War. Oh, and as my daughters often remind me, “Bowdoin people are everywhere.”

With Best Wishes,

John R. Cross ’76

Secretary of Development and College Relations