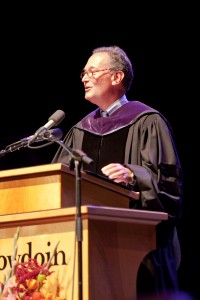

Barry Mills on the Challenges Ahead for Liberal Arts Colleges

In his annual Opening of the College address, President Barry Mills tells a standing-room only crowd in Pickard Theater that liberal arts colleges like Bowdoin must deal with the widely held perceptions that their costs are out of control, their views are out of touch, and that their opportunities are available only to a privileged elite. Watch the video, or read the full text delivered Wednesday at the 209th Convocation of Bowdoin College.

Good afternoon. It is my honor to preside at the official opening of the 209th academic year of Bowdoin College.

Today, I am very pleased to welcome our faculty, staff, students, and friends to this traditional ceremony, and to offer a particular welcome to the members of the Class of 2014. I am delighted that so many members of our impressive first-year class have come to celebrate with us. During the past couple of days, I have had the opportunity to greet and chat briefly with each of you in my very steamy office, and to watch you join the generations of students before you who have begun their Bowdoin careers by signing our Matriculation Book. I can confidently say to our faculty and staff that the Class of 2014 is energetic, serious, and talented, and that its members are clearly ready for all that Bowdoin has to offer. I know they will make important and lasting contributions to the College over the next four years and beyond.

It is my practice to focus my remarks at Convocation—as well as those delivered during Baccalaureate in the spring—on issues and ideas of importance to the College. In the past, I have used this forum to discuss the centrality of the arts in the liberal arts, academic freedom, sustainability, the fundamental importance of financial aid, issues of race and socioeconomic class, and how campus construction and renovation supports our academic program.

Today, as we begin this new academic year, I will address conflicting themes that have me confused, uncertain, and genuinely concerned about the vitality and viability of the liberal arts sector in general and, to some extent over the very long term, Bowdoin in particular.

I have to admit that as I begin my tenth year as president of Bowdoin, it troubles me to present questions for which I don’t have the answers. Then again, these are the questions that keep the job of leading this great College interesting and challenging.

On one side of the equation, we gather today on the campus of one of the most popular and most respected liberal arts colleges in America. By all objective measures—and by many that are subjective—Bowdoin stands today at the top of the education marketplace. These exceptional first-year students here today were among more than 6,000 applicants seeking to gain admission to the Class of 2014. Over 6,000 applicants, of whom we were able to admit a mere 17 percent. And the number of admitted students who accepted our offer of admission was phenomenal—well beyond our expectations. So today, we welcome the largest first-year class in our history: 509 students, with one additional student still trying to obtain a visa to join us. I have no doubt that this class is among the most serious and most talented group of students we have ever admitted.

Of course, Bowdoin’s strong reputation and popularity create challenges—challenges that are in the category of “good problems to have.” This year, we project we will be a college of about 1,750 students, and that’s just about where we seek to be, after taking account of students studying away. In the recent past, the percentage of students supported by Bowdoin financial aid has increased from 35 percent to 41 percent to nearly 47 percent for this Class of 2014. This is a fantastic achievement for the College, but managing the size of the class next year to around 485 students will be a serious challenge, especially as we seek to matriculate the enormous talent committed to Bowdoin. And gauging our financial aid capacity in this troubled economy will also be hard work. But again, these are good problems to have.

The enthusiasm for the College by our current students and their parents is gratifying for all of us who work to advance excellence at Bowdoin. We are proud of the enthusiastic endorsements of the College by our most recent graduates, and we applaud the success they have achieved since leaving here in May.

Our alumni continue to support Bowdoin at impressive levels. The Alumni Fund was a tough slog this year, but we impressively hit our goals in a troubled economy. The Parents Fund was at a historic high level. And last June, more than 60 percent of the Class of 2005 returned to campus for their fifth reunion. For those who know us best, Bowdoin continues to be an institution blessed with extraordinary loyalty and recognized for its excellence, its principles, and its mission.

So, what’s the problem? What’s the conflict represented by the other side of the equation? Well, this summer I spoke to a loyal group of alumni and friends of the College. All they wanted to talk about was how we can possibly justify and sustain the cost of a Bowdoin education—with a comprehensive fee of nearly $53,000 and the true cost of educating each student approaching $87,000 a year. Understandably, the folks in that room wanted to know how we expect Bowdoin to be accessible to their grandchildren.

The view clearly stated was that although the College is fantastic, the model is unsustainable. Bowdoin cost too much. These folks—like many I meet—are just unable to comprehend our plan for the future and how we intend to pay for it.

I am questioned on this issue everywhere I go. How can we justify the cost, and do we really expect to continue to be able to escalate these costs into the future? I argue, as I always do, that we only need to attract a small number of students to allow Bowdoin to thrive, and that this is a large country and world. Of course, this doesn’t mean we will simply fill our classrooms and residence halls with those fortunate enough to be able to pay our fees. Some students will come from families who can afford Bowdoin. Others will be students from families that can’t afford the fantastic price of a Bowdoin education—students who most definitely ought to be at Bowdoin. For these students, we will continue to work hard to have the resources necessary to bridge the financial gap.

All of this begs the question for the many liberal arts colleges that are not perceived to be of the same quality as Bowdoin. And frankly, I am met with skepticism even when I talk about the situation here. Simply put, there is genuine mistrust of our financial model, as folks extrapolate into the future based on our past practices, especially during these very uncertain and very troubled economic times that could easily continue for a decade or more. This skepticism is one of my unsolved dilemmas. It is a serious issue for the College going forward, and one that goes beyond the very real issues of cost and affordability. It is an issue that goes to the credibility and veracity of the College.

There is also the issue of our relevance or, to put it another way, our connection to the sense of American society today, and to the world. Please allow me to share three quick stories.

First, back to that summer night talking to a loyal group of Bowdoin supporters. One person in attendance—a grandfather—told me he spends his winters in a southern state and that none of his neighbors there would ever think of sending their kids to Bowdoin, given the lack of diversity of views here. We are, they believe, simply a liberal hotbed disconnected from reality. They fear that their kids will be educated in a way that will make them not want to come home. Why spend all that money to send their sons and daughters to a place where the education will break family bonds and where the ideals are inconsistent with their family and community values?

Then there was my day on the golf course a few weeks ago up north. As some of you may know, I have grown addicted to the game of golf, as evidenced by the vivid color of my face and this most unhealthy tan. Now, this is not exactly a golf story. I was playing really well (at least, really well for me) and my partner in the match was very happy. At the tenth hole, I hit a fantastic drive that travels about 220 yards. I’m about 180 yards from the green, and as I take my backswing with my six-iron, my opponent announces mid-swing:

“I would never support Bowdoin—you are a ridiculous liberal school that brings all the wrong students to campus for all the wrong reasons.”

Zing! My shot goes directly sideways into the woods. I will spare you the golf details, but right in the middle of my next backswing, the guy declares:

“And I would never support Bowdoin or Williams (his alma mater) because of all your misplaced and misguided diversity efforts.”

At this, I feel myself turning bright red. I swing wildly, nearly hitting my partner in the head with the ball as it squirted to the right. I lost the hole, but no worries, I’m a bit competitive and so was my partner. We won the match and the money. But I walked off the course in despair and with deep concern.

Finally, I remember the conversations I have had over the past couple of years with someone close to me—a person deeply rooted in the Midwest. This person is genuinely committed to excellence in education, but she always points out to me that even the executives in her company can’t afford a place like Bowdoin, and that they don’t see the value of what they describe as this very precious education—there are plenty of state schools with Midwest cost structures and with values that make more sense to them. Our place is just too liberal and too expensive.

All summer I have been reading the op-ed pages, columns from David Brooks to Paul Krugman, and the editorial pages of The Wall Street Journal to the Atlantic Monthly—all pointing out the deep distrust of America’s “liberal institutions” and their disconnect from our country. People are clearly on all sides of this debate and controversy, but the deep sentiment is that we are out of touch.

I have no statistics to quote for Bowdoin, but if we are representative of elite liberal arts colleges, we are, in the main, a place of liberal political persuasion. In his recent book, The Marketplace of Ideas, Why Do All Professors Think Alike?, Louis Menand references a study done in 2007 by Neil Gross and Solon Simmons suggesting that about 44% of the professoriate is some kind of liberal and that only about 9% is some kind of conservative, with the remainder somewhere in the middle. Professor Menand postulates all sorts of reasons for these results, ranging from the perspectives and life history of the folks going to graduate school, to the time to degree, to the financial prospects of a life in academics. But at the end of the day, his work supports the narrative that elite education is dominated by liberal perspective.

Which all leads me back to my concerns. Should I worry that we are viewed as pricing most folks out of Bowdoin and worse, that we are insensitive to the issue of cost? This, incidentally, is a view commonly held by some of our most loyal supporters. Should I care that many believe Bowdoin’s values don’t represent the views of so many in our country? Should we be concerned that Bowdoin—the school grounded on McKeen’s sense of the Common Good—is perceived by many as a bastion for the privileged elite, even as we open the doors to success for a new set of individuals from all socioeconomic and racial backgrounds each and every year?

My guess is that some among you think what I describe is a non-issue. It is my overreaction to this “Glenn Beck, Sarah Palin moment” in our history. But I don’t think that’s what I am reacting to. And given our economy and the uncertainty in our nation, this is not a time to be sanguine about the reputation or standing of any institution in America just because it has long been held in high regard.

So what do I do with all this? As my predecessor, President Edwards used to say so often: “Therefore, what?” There haven’t been many “Therefore, what?” moments over the past ten years because, for me, the path forward has always appeared so clearly ahead. As I stated at the outset, it troubles me to present questions for which I don’t have the answers. That said, I do have a few ideas on how we might address these dilemmas.

First, on the financial issues, we must do a better job of communicating our plans for our economic future in a manner that is transparent, but also in ways that are more than transparent. We have to also be realistic and credible. This means analyzing the future of Bowdoin in an environment where comprehensive fee increases may have to be moderated significantly. This reality, if necessary, will have real effects on the students, faculty, and staff of Bowdoin. It will have serious effects on program throughout our community. And it means stepping up to the challenge of providing more financial aid to students who ought to be at Bowdoin. Our financial aid endowment is strong and substantial, but as I said to our alumni at the Reunion Convocation just last spring, we have no choice but to continue to build our financial aid revenues and to grow our endowment for financial aid. If we have the financial aid endowment to support our students, we can mitigate the impact on our operations and program caused by a reduced comprehensive fee.

This is not an uncomplicated analysis for the College, especially because we cannot strategize for our future with an eye in the rear view mirror. There are just as many economists who worry about a deflationary economy in our nation over the next period as there are economists seriously concerned about inflation and the national deficit—this is the world we live in today. At a College where ambition for excellence is linked directly to increased cost, the calculus will be very different, depending on which of these two economic scenarios takes hold.

Second, we must be willing to entertain diverse perspectives throughout our community. We have made real progress on this issue in our student body and on the Bowdoin staff. And we have made significant progress in the faculty over the past few years. But diversity of ideas at all levels of the College is crucial for our credibility and for our educational mission. Civility and respect are essential at Bowdoin, but we must guard against political correctness and a culture where everyone—students, faculty, and staff—is supposed to feel “comfortable.” We value, as one of our highest priorities, the Bowdoin sense of community and collegiality, and we should continue to do so. However, we should be willing to incorporate more vigorously a diversity of views into that sense of community. Creative tension is a positive force in a community committed to intellectual excellence and vitality.

There should never be a time when we have a political litmus test for faculty or even inquire about political persuasion. In my view, this is simply not relevant to the intellectual enterprise of the College. But at the same time, we should be willing and more active in bringing to this community recognized and accomplished scholars—as visitors or tenure-track professors—who engage their disciplines, academic work, and artistic work with perspective different from the conventional wisdom at Bowdoin or on other campuses. This different perspective will energize our classrooms and the intellectual life of our faculty and our community.

And, finally, we must all seek to be important. Don’t misunderstand “importance” as “relevance.” I actually do not focus on our striving for relevance, because relevance is a fleeting virtue. Nor do I mean importance as in “famous,” for that can be fleeting too. What I intend for Bowdoin—for all of us—is to establish ourselves as individuals in our society who are doing work that is recognized as making a valuable contribution. For students, that means, first and foremost, work in the classroom and in the life of the campus and later, as Bowdoin alumni in your communities. For staff, it means being innovative and creative in how we do our work. And for faculty, it means being routinely excellent teachers dedicated to inspiring our students, while at the same time, doing the hard work on your scholarship, research, and artistic endeavors that brings recognition in your field as a valuable contributor throughout your career.

This commitment to doing important work will benefit Bowdoin and ensure our lasting value in society. At the same time, it will be enormously rewarding and fulfilling for each of you. I am not suggesting that this formula is easy or without effort, but given the privilege we all enjoy at Bowdoin, we owe that level of commitment to each other and to the legacy of this College.

These are by no means all the measures we should consider to ensure our future, but they are certainly among the necessary steps. I will continue to work with all of you in a cooperative and transparent manner as I grapple with the dilemmas I have described and to ensure Bowdoin’s future for all.

In closing, let me be explicit that, in my view, a Bowdoin education is at the heart of this nation’s democratic traditions and central to our democratic future. We should reject with confidence any assertion to the contrary.

Martha Nussbaum from the University of Chicago recently has written: “All modern democracies…are societies in which the meaning and ultimate goals of human life are topics of reasonable disagreement among the citizens who hold many different religious and secular views, and these citizens will naturally differ about how far various types of humanistic education serve their particular goals. What we can agree about is that young people all over the world, in any nation lucky enough to be democratic, need to grow up to be participants in a form of government in which the people inform themselves about the crucial issues they will address as voters and, sometimes, as elected or appointed officials.”

Nussbaum states further “…that cultivated capacities for critical thinking and reflection are crucial in keeping democracies alive and wide awake. The ability to think well about a wide range of cultures, groups, and nations in the context of a grasp of the global economy and of the history of many national and group interactions is crucial in order to enable democracies to deal responsibly with the problems we currently face as members of an interdependent world. And the ability to imagine the experience of another—a capacity almost all human beings possess in some form—needs to be greatly enhanced and refined if we are to have any hope of sustaining decent institutions across the many divisions that any modern society contains.” (Martha C. Nussbaum, Not for Profit, Why Democracies Needs the Humanities, pages 9-10.)

Simply stated, this is what a Bowdoin education is about – the preservation of our tenets of democracy. It is our mission—it is “The Offer of The College”—and it deserves our support and demands our collective commitment.

I now declare the College to be in session. May it be a year of peace, health, success, and inspiration for us all, and a recommitment to our most important tradition: teaching and learning together.

Thank you.