A Suitcase of Stories

By Ian Aldrich for Bowdoin MagazineSoccer and swim coach Charlie Butt’s improbable journey from acclaimed Shanghai athlete to legendary Bowdoin coach and national squash champion began with a dramatic swim in a frigid Chinese harbor, a daring escape, and a small brown suitcase.

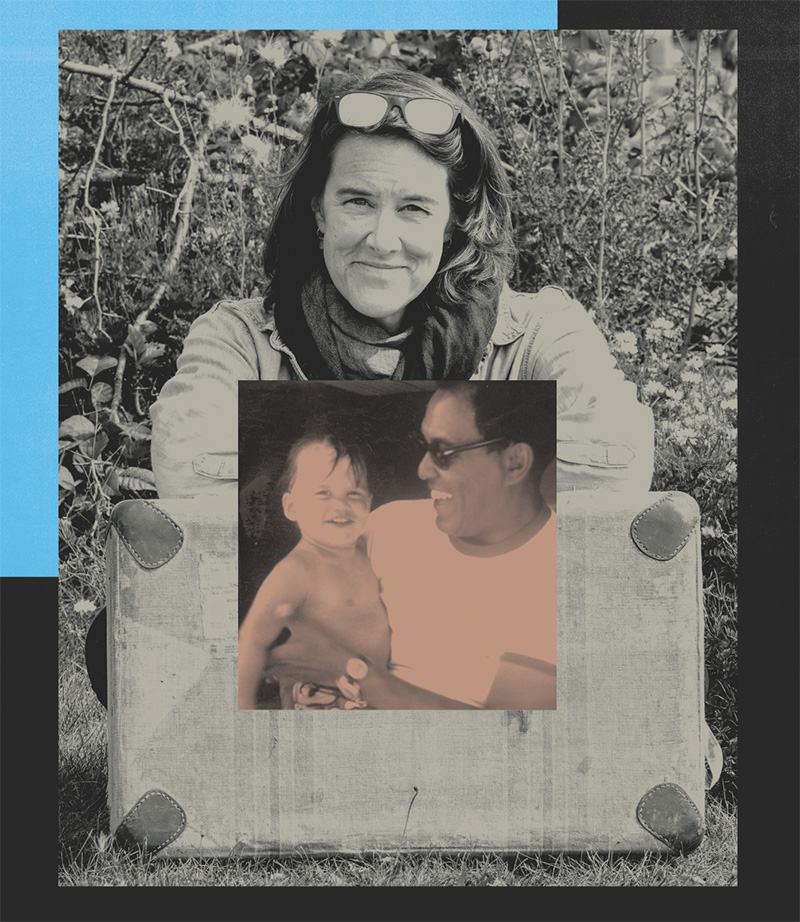

Nearly seventy years after that fateful February day, Charlie’s daughter started asking questions. This summer, she published a book that shares his unlikely and impressive life story with the world.

The sit-downs felt like a gift. That was overwhelmingly clear to Cathleen “Catie” Butt even in the moment she took her seat next to her father in the solarium of his home in Harpswell, Maine. There, amid the ocean views and a steady rotation of salty snacks, coffee, and visits from his adoring dog, Cosmo, her ninety-three-year-old dad unspooled the story of his fascinating life with an energy and clarity that stood in defiance of his waning health. But then, Charlie Butt had never let an obstacle, no matter its size, get in the way of something he wanted to do.

The prompts he had managed to bring with him when he stowed away on a British cargo ship leaving Tientsin for Hong Kong helped. The yellowed photos of his youth in Shanghai. The weathered newspaper stories documenting his many sports triumphs there. The personal histories and pages of transcripts from a round of interviews that Charlie had given several years before—Catie pored over it all. Who was this person? What happened here? Where was this? How did you get here? After so many years of largely staying quiet about parts of his past, Charlie had at last sat down with his daughter to help him reflect on what had come before.

“My dad was very good at compartmentalizing his life,” says Catie. “Which is what he needed to do. He wanted to focus on where he was and what he needed to do: creating opportunities, solving problems, and not being weighed down by the past.”

“So, if you didn’t know to ask, you wouldn’t have known he had this whole other part of his life that he had come from.”

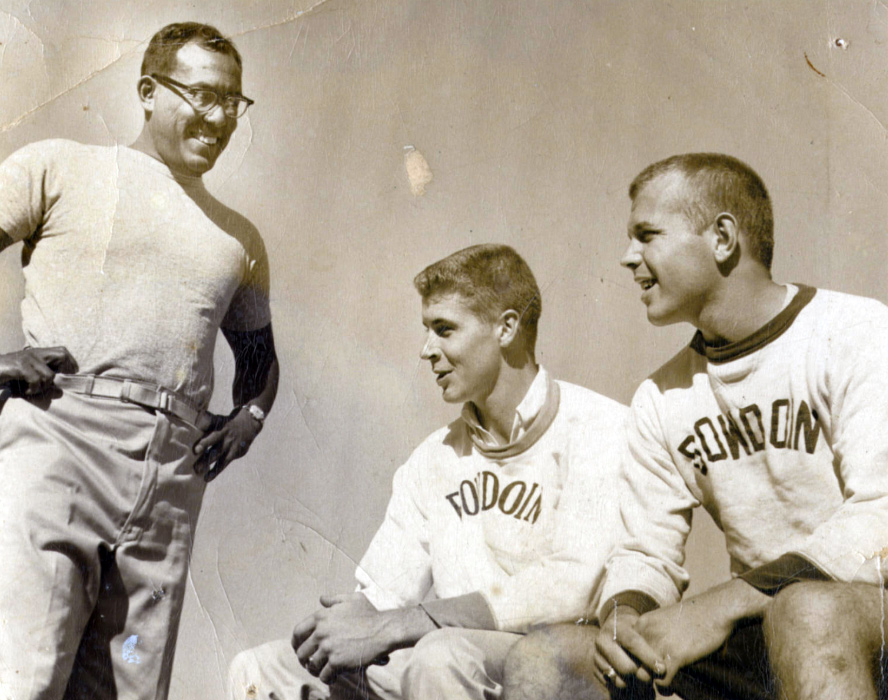

A presence on campus for four decades, Charlie needs no introduction to many in the Bowdoin community. He arrived in Brunswick by way of Springfield College and Long Island, New York, in the fall of 1961, and over his career he didn’t just pioneer Bowdoin’s entry into swimming and soccer, he fostered generations of success. The accolades are long: undefeated seasons, New England Championship appearances, rosters of All-Americans, rounds of coaching recognitions, and inductions into various Halls of Fame.

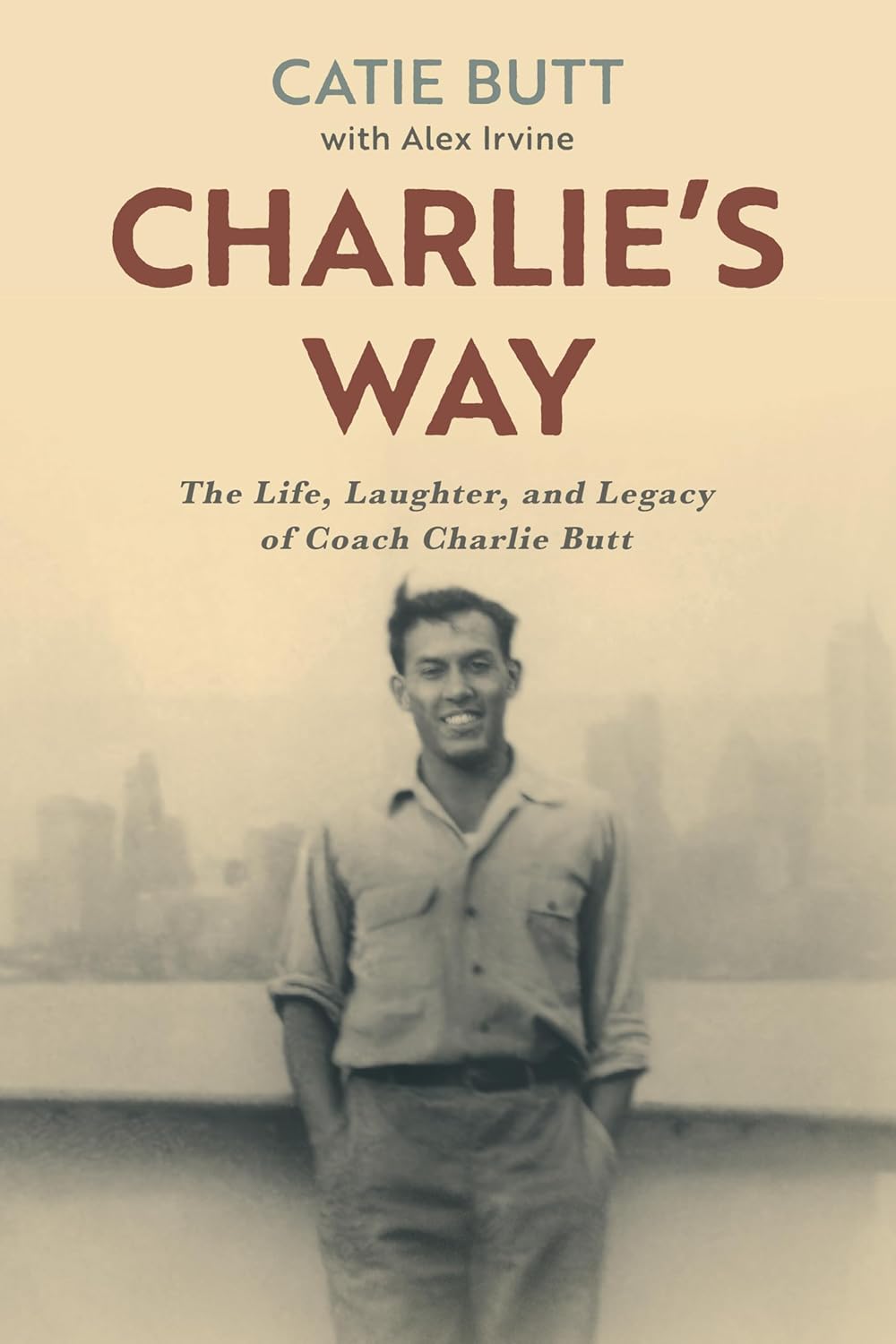

But the familiar story is also incomplete. Charlie’s childhood in a complicated and changing Shanghai, his determined path to America and later Bowdoin, the underpinnings of his new life in Maine—these were stories Catie Butt wanted to explore when she first sat down with her dad in March 2018. Charlie died that September, but in those final six months together, the two made the most of their time, and the result of those sessions—along with hundreds of hours of research Catie clocked after her dad’s death—is captured in her new book, Charlie’s Way: The Life, Laughter, and Legacy of Coach Charlie Butt. Published in collaboration with Bowdoin College, proceeds from the sale of the book directly fund the Charles J. Butt Scholarship Fund.

“He really was an inspiring person,” says Catie. “He was resilient and hard-working, but he also cared about others and was open-minded. He had this incredible life, both at Bowdoin and before it, and I wanted people to know the full story.”

In the opening pages of her book, Catie writes a telling detail about her father. “Dad could only have come from a city like Shanghai, and the more I learned about its history, the more I could see how being not just Eurasian but Eurasian from Shanghai had made Dad the man he became.”

The Shanghai that Charlie Butt was born into in 1925 was a city tumultuously straddling two different eras. As it reeled from the aftershocks of a 1911 revolution that had ended 2,000 years of imperial rule, Shanghai also became fertile ground for the rise of the Chinese National Party, setting in motion the workings of another kind of national upheaval. Even amid this swirl of competing interests, international commerce furiously grew and modernized the city, bringing not just new roads and hotels but foreign cultures, ideas, and identities to Shanghai life.

“It must have seemed all the world was there,” Catie writes. “The expensive cars of European merchants and diplomats, the crisp uniforms of British and American sailors on leave, the turbaned Sikhs who formed the backbone of the International Settlement’s police force, the vendors selling everything from cloth to live animals to ta ping yu se kwei, a Chinese take on American fried dough that was one of Dad’s favorite street-food treats, the smells of coal stoves and emptied chamber pots, the public executions and children playing games in the street, the beggars and the laborers, the horns of ships in the harbor and cars on the streets. The world came to Shanghai, and young Charlie Butt soaked it in, waiting for his chance to get out and see it all.”

Charlie was fortunate. Born to Chinese-Portuguese parents, his family resided in an area of the city known as the French Concession, an international carve-out established after the 1911 revolution that allowed its residents to largely live under the banner of Western law. As Chinese residents outside the zone suffered under an increasingly repressive national government, those within it led a life with limited restrictions. The friendships and the backgrounds of those whom Charlie befriended cut a wide swath, including “the children of Russian refugees, European diplomats, [and] American missionaries,” writes Catie.

Charlie’s natural ability to make new friends was augmented by his athletic abilities. A theme throughout his life was his knack for excelling at almost any sport he tried. That included a turn to squash in his forties that resulted in twenty-three national championships within his age bracket (singles and doubles) as well as a world title. It began early: boxing, basketball, soccer, tennis, and swimming—these were the sports that Charlie didn’t just instinctively take to as a youth, but shined at.

“I think he really had that in his back pocket all the time,” says his son, Charlie Butt Jr. (known to family and friends as C2). “I don’t know if he knew how gifted he was, but he probably did. He told me stories where he’d be somewhere in New York and someone would be like, Charlie, I watched you play basketball in Shanghai. He was shy and modest about it, but he also loved it, of course. It was a part of his life.”

His natural gifts, says Catie, were apparent even to the untrained eye. But if that’s all you saw, then you missed what undergirded those physical attributes: his intellectual instincts.

“He somehow had a feel for people and for the game and for strategy and [as a coach] for understanding where to put different players with different skills and strengths,” she says. “You have to be smart in the way you approach a sport, and respectful of the activity and the people involved.”

As Charlie found his footing as an athlete, however, the ground underneath grew more unstable, made more so by the encroachment of World War II. After graduating from Western District Public School in 1941, Charlie enrolled at St. John’s University in Shanghai, but his studies came to a halt after two years following the Japanese occupation of the city. When the war concluded, Charlie resumed both college and his prolific athletic career. He earned a spot on the national basketball team and set Chinese records in swimming the 50-yard, 100-yard, and 100-meter freestyle. His talent was more than just the stuff of local lore: In 1948, Charlie qualified for the Olympic Games in London in both sports. But his refusal to turn in his Portuguese passport to Chinese authorities put Charlie in the crosshairs of the new Communist government, and in 1951 he made a daring escape to Hong Kong via a British cargo vessel. He eventually made his way to Tokyo, where he secured a visa to the United States to attend Springfield College, where he had been admitted before the start of the war.

Charlie found a new home at Springfield, graduating cum laude in 1953 and later earning his MS. He found equal success as an athlete. Charlie was an All-American soccer player in 1952 and 1953, and he captained both the swimming team and tennis squads. He was also a member of the national championship volleyball team in his first year on campus.

In the fall of 1961, Charlie arrived at Bowdoin as its varsity swimming and soccer coach. It’s unlikely anyone could have forecasted how central he’d be to the College’s athletic programs over the next four decades. Just as it’s equally unlikely anyone, maybe even Charlie, could have predicted the success he’d oversee. His 1962 soccer squad won a share of the first Maine Intercollegiate Athletic Association soccer title, then won it outright in 1965, 1966, and 1968. His 120 career wins are still the most in the program’s history.

As the men’s swimming coach, meanwhile, Charlie steered the club to its first-ever undefeated season during his inaugural year at the helm. The team also placed second at the New England Championships, an accomplishment Charlie’s program achieved four more times. In addition, the coach presided over the launch of the women’s swimming program in 1976–1977. Just a dozen years later, the program finished atop the leaderboard at the New England championships. During his long career, Charlie amassed a record of 132-65 in dual meets with the women’s team and 198 wins with the men’s squad. Along the way, more than one hundred of his swimmers earned All-American honors.

Come summer, Charlie anchored himself as the aquatics director at the Piping Rock Country Club in Locust Valley, New York, an exclusive Long Island enclave “where some of the nation’s most prominent and wealthy families have added their names to the club’s membership rolls,” writes Catie. For fifty-seven years, her father was a beloved fixture of Piping Rock’s summer scene, so much so that upon his retirement in 2010, the club named its pool after him.

Springfield, Bowdoin, Piping Rock—at the time Charlie walked through their respective doors, these were not environments that necessarily had a long history of welcoming young Chinese immigrants into their ranks. But Charlie broke through in part because, as good as he was at assimilating to new environments, he also never strayed from who he was. In her book, Catie quotes her father’s recollection of his job interview at Piping Rock. Charlie wasn’t blind to the world he was walking into, and he was determined to make sure the club’s directors also weren’t blind to how he expected to be treated.

“I met with three or four people individually,” Charlie remembered. “I wondered if he was thinking how he was going to put Charlie here with all us white, Protestant buggers? A strange-looking man from out of nowhere. I was Asian, with dark skin, and there was a lot of anti-Asian sentiment those days. So, finally they said they wanted to proceed. And I said, ‘Okay.’ So, then I thought about the conditions I had heard about and that we could potentially have. I said, ‘Let’s get something straight right away if I’m going to be a teacher here. I am used to teaching at a college. When people come up to me here, you pay me that respect. I’ve heard that some pros are treated like servants, and I won’t have any of that. I’m a teacher, I’m a coach, I will run the program. I want people to call me Mr. Butt or Charlie with the right tone. I heard you say earlier that I could go eat in the back room with the chefs and all of that. No, if I’m here, I’m going to eat out here with the members and everybody else.’”

This was not an isolated moment. Charlie’s sense of fairness—for himself and those around him—was as much a part of his identity as the white sun hat that was perched atop his head during his days at Piping Rock. To know her father, says Catie, was to know a person whose empathy, courage, and authenticity helped explain how he was able to make the long journey from Shanghai to Brunswick.

“He knew he came from different circumstances,” she says. “That he had a different background and looked different in a lot of environments. But he was not going to allow those things to stand in his way.”

Charlie's Way was a true labor of love for Catie Butt—and at times became its own kind of challenging journey for her. Working around her own busy career as a corporate attorney, the pandemic, and, of course, the loss of her father as she embarked on the research, she took some ten years to complete the project. But Catie didn’t cut any corners. She read deeply about the history of Shanghai, including personal accounts from those who’d grown up in the city during the time her father was a boy. She unearthed old newspaper articles, sifted through piles of photographs, and studied folders of letters written to the family after Charlie’s death—all in a dogged attempt to better understand her father and the different lives he’d led.

“I really came to appreciate the impact my dad had on so many different lives and all the different branches of what he would do for people,” says Catie.

In all, she also interviewed more than sixty people who were associated with her father for the book. Friends, colleagues, students—the narrative is chock full of accounts of those who found their own lives enriched by their connection to Charlie Butt.

“Charlie inspired us all,” said Rob Moore ’77, cocaptain of the New England champion, NCAA-semifinal-reaching Bowdoin squad in 1976 who went on to play professionally and was a winning coach. “I played soccer for him for four years and learned so much. He had a way of letting us play the game, not micromanaging, but teaching us through his positive attitude, his electric energy, and his constant support. We won so many games in my four years. He knew which players to play and where to get the most out of them on the field. I consider him one of the best coaches I’ve ever had.”

In one instance, Catie used a family trip to Florida to visit Betty Grebenschikoff, a childhood friend of her dad who has since also died. “She was the only living member of that whole crew, and her memory was rich and perfect,” says Catie. In another, she interviewed a group of Division III swimming coaches from across the country who invited her to join them on their monthly Zoom call. “They talked about their business stuff at the top of the meeting and then let me have the last three-quarters of the call to just ask questions and collect their stories about my dad,” she says.

Catie also labored over the writing. By 2019 she had drafted fifteen chapters, but scrapped them all because the storytelling wasn’t where she wanted it to be. In her own research, she had struggled through a number of poorly written memoirs and histories. If she was going to honor the richness of her father’s life, Catie says she wanted to publish something that people would actually want to read.

“I thought a lot about what I wanted to include,” she says. “Just because something was interesting to me didn’t necessarily mean it would be interesting to someone else. I’d never done anything like this.” She laughs. “I write contracts and PowerPoint presentations. But I wanted [this book] to be an easy read so that even if you didn’t know my dad, you’d find the book enjoyable.”

But Charlie’s Way is also a family record. An in-depth attempt to not just document Charlie’s full life, but also to remind those who have and will come after him who they come from and what they are also capable of. C2, who read an early draft of the book, thinks his sister has accomplished that in spades.

“Rereading the history, and just having it put together chronologically in a much more defined way, allowed me to learn more about how he grew up,” says C2. “I’ve got four kids here now, and they all loved him and enjoyed the time they had with [their grandfather]. So, I think having them understand more of who he was is really powerful for the family.”

On a Friday in early July, I met with Catie Butt in Morrell Lounge in Bowdoin’s Smith Union. She is tall and athletic and carries herself with the measured demeanor of someone accustomed to navigating highly competitive spaces, from corporate boardrooms to the swimming pool (she was an All-American swimmer at Ohio Wesleyan University). In tow was a copy of Charlie’s Way, which had just been published a few days before, and a poster announcing its arrival hung on a nearby wall.

It was a fitting place to meet. When they were kids, Bowdoin was a second home for Catie and her brother, including the building where we met, which in a previous life was an athletic center, Hyde Cage, with an indoor track above the main floor. Catie motioned above where we were sitting. “We spent a lot of time up there,” she said with a laugh. And elsewhere. They raced around the grounds of Whittier Field, played hide-and-seek among the pines that tower over the stadium, and rang up their father’s charge account at Moulton Union Dining Hall.

“We knew every nook and cranny of these buildings. This is where we grew up, in a sense. Just little brats running around, and not always with adult supervision. If our friends were with us, their parents knew exactly where they were. We were at Bowdoin, and that was okay.”

Charlie established a part of his life at Bowdoin, and in doing so, so did his children. As high schoolers, Charlie Jr. and Catie used the campus facilities as their own training ground. Charlie Jr. practiced hockey and soccer, Catie swam and ice skated, or stationed herself in Gibson Hall to rehearse piano.

“At my dad’s ninetieth birthday, there was a big party for him [at Bowdoin] the alums had organized,” Catie recalls. “When I spoke that night, I said I felt like an honorary Polar Bear for sure, and people totally got that. There’s a real association that we feel to this institution.”

After we talked, Catie and I walked across campus to her car, where she had a few items from her father’s life to show me. There was a pair of plaques that honored his recognition as an All-American college soccer player in 1952 and 1953. Tucked around them was an even more important piece of family lore: the safety belt Charlie used in the late 1950s, when he was hired as a diver to retrieve tools that workers accidentally dropped in the East River during the building of New York City’s Throgs Neck Bridge.

“Throughout his life, whenever the bridge came into view, Dad never missed an opportunity to ask any members of our [usually eye-rolling and grumbling] family who were within earshot, ‘Did I ever tell you how I helped build that bridge?’” Catie writes in Charlie’s Way. “The more the story was told, the more he seemed to enjoy impishly concluding that construction of the Throgs Neck Bridge would never have been completed without him.”

But these pale in comparison to what Catie has also brought: her father’s suitcase from Shanghai. It’s worn and slightly stained, but all of its handsome features remain: its leather trim, its metal locks, its decorative colored stripes. A faded prepaid label still clings to its top. The suitcase is also impressively small—maybe two feet wide. But oh, what it packed. Not just clothes and mementos, but dreams and hopes.

Looking at it now, it’s awe-inspiring to think about all that emerged from this single piece of luggage. The young lives Charlie mentored. The family he built. The unique friendships he forged. The unmatched legacy he left behind.

And it all started with a swim.

Ian Aldrich is the deputy editor at Yankee Magazine.

Mark Harris is an award-winning graphic designer whose work has been featured in The New York Times, The Atlantic, and many other publications. See more of his work at mrkhrrs.com.

This story first appeared in the Fall 2025 issue of Bowdoin Magazine. Manage your subscription and see other stories from the magazine on the Bowdoin Magazine website.