Beware the “Cabaret Syndrome.” Exploring the Weimar Republic’s Cultural Legacy

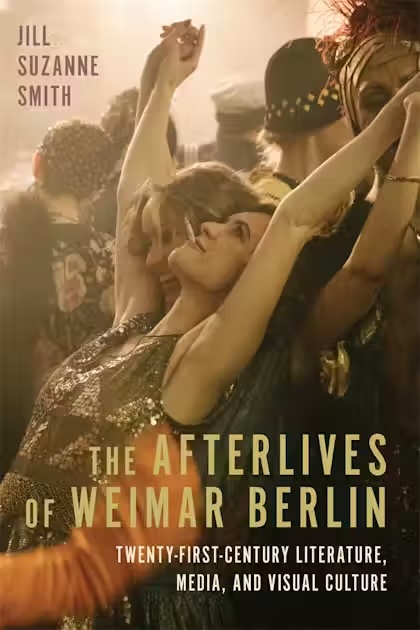

By Tom PorterIn her latest book, Associate Professor of German Jill Smith explains her frustration at a tendency to oversimplify a key period of twentieth-century European history—and it’s all down to a 1970s musical movie.

“When you mention the Weimar Republic, what do most people think of? The movie Cabaret,” said Smith, referring to the highly acclaimed 1972 musical period drama set in early 1930s Berlin. This has led to a phenomenon Smith described as the “Cabaret syndrome.”

She was speaking at a book launch in early May to mark the publication of her latest work, The Afterlives of Weimar Berlin: Twenty-First-Century Literature, Media, and Visual Culture (Camden House / Boydell and Brewer, 2024). The book questions the traditional portrayal of this era, which covers the fourteen-year period after the First World War when Germany was governed as a constitutional democracy for the first time in its history. This was brought to an end by the rise to power of the Nazi Party under Adolf Hitler in 1933.

The movie Cabaret, which is based on the successful stage musical of the same name and features a number of memorable song and dance routines, is set in the later days of the Republic and is seen through the eyes of an American showgirl and nightclub entertainer, Sally Bowles (played in the film by Liza Minnelli). Sally performs her risqué routines at the Kit Kat Klub, a seedy and Bohemian establishment in Berlin.

As her personal story plays out, the movie’s central theme—the rise of Nazism—becomes ever more noticeable. Swastikas become increasingly commonplace and, by the end of movie, Sally is performing for a clientele that predominantly comprises Nazis. “At the very beginning of the film we have few indications of the rise of the National Socialists,” observed Smith, “but by the end they populate the audience at the Kit Kat Klub, and we get the sense that the show is being put on for them.”

The movie’s huge success and its enduring appeal (there was a stage revival of the show on Broadway in 2024) means it has become difficult to separate the Cabaret-influenced view of Weimar from the actual history, she said. So many tropes have emerged from the film, she added, “We get this idea of politically naïve, slutty showgirls, pandering to fascists, amidst a decadent, doom-laden, promiscuous party atmosphere.”

In her book, Smith asserts that the film portrays a “causal relationship between decadence and fascism suggesting that Weimar culture allowed, through indifference, neglect, or complicity, the development of a politically oppressive regime.” This is an unfair portrayal, Smith said, and a central plank of the “Cabaret syndrome.” In a conversation with Associate Professor of English Ann Kibbie, Smith explained how this syndrome, most prevalent in the Anglo-American world, consists of two major symptoms:

The Temporal Symptom. This relates to a timeline of events, said Smith, explaining how the film gives the impression that the Weimar Republic only refers to the early 1930s, the period directly before the National Socialists came to power. This means we don’t get a full view of the era, which began in 1919, and its complexities.

The Spatial Symptom. This gives a false geographic impression of the Republic, implying that Weimar is Berlin, rather than the entire German state. “This means we ignore the areas of innovation outside the capital city and are blind to conservative forces that remained intact in more provincial areas,” explained Smith.

This book is an effort “to really expose that syndrome … that just keeps coming up in works of literature and scholarship,” said Smith, “and also to celebrate those works that are calling that into question.” There’s been a renewed scholarly interest in the Weimar period since the turn of the millennium, she explained, something that The Afterlives of Weimar Berlin taps into in its five chapters.

The work explores the creative interplay between contemporary and historical texts, their contexts, and their creators, tracing a cultural legacy that has the work of German Jews and women as its foundation.

The end result, said Smith, should be a more accurate vision of Weimar and its cultural legacy, rather than the impression given by a narrow piece of cinematic fiction.

Last year Smith collaborated with the University of Maryland’s Hester Baer to put together the first scholarly book on various themes explored in the hit German language TV show Babylon Berlin, which is also set during the final years of the Weimar Republic. Read more.