Prince of Tweeds

By Ian Aldrich for Bowdoin MagazineIf clothes make the man, then Charlie Davidson—a tailor who loved making people look good, who dressed jazz musicians and professors, who briefly graced the Bowdoin campus before heading off to war—is who you want to make the clothes. Davidson loved fashion, and The Andover Shop he founded became a hub for others who did too. But style was more than clothes. Culture, curiosity, and confidence fed both his look and his life.

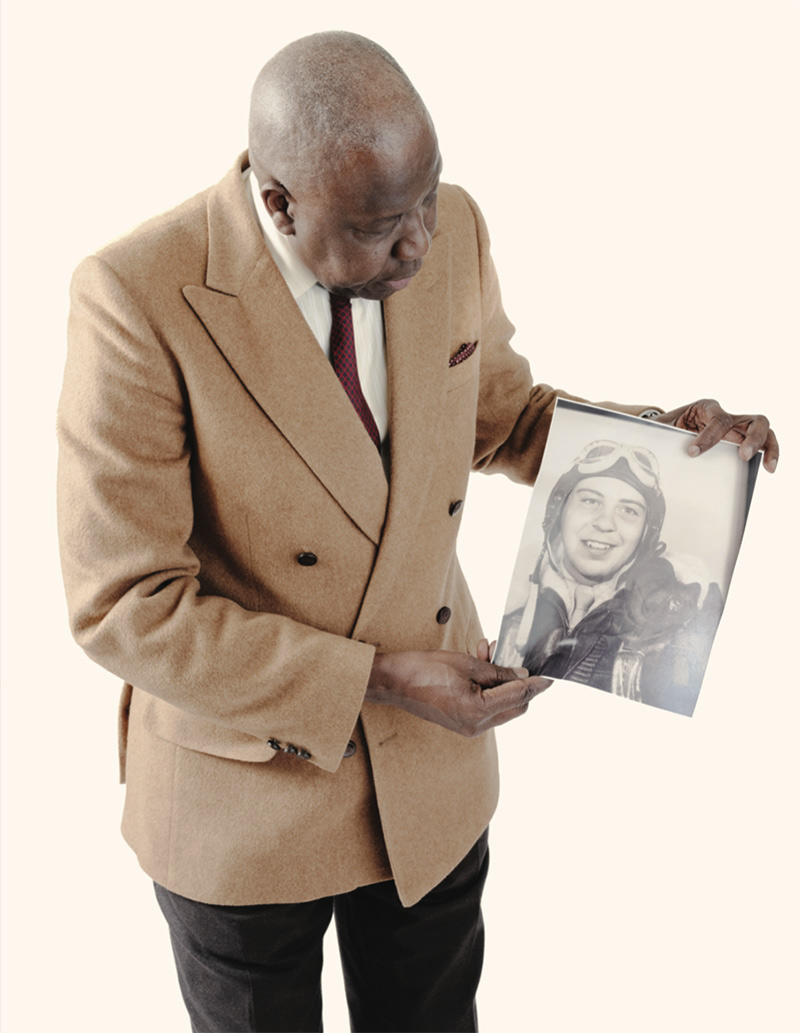

Mor Sene, holding a photo of Davidson as an Air Force gunner serving in the Pacific during World War II.

In the fall of 1988, Mor Sene made a phone call that would change his life. Born into a family of tailors, Sene was an experienced clothes maker in his own right. He’d studied cutting and patternmaking in Paris before returning to his home country of Senegal, where he had spent several years teaching at the Fashion Institute of Dakar. When political strife unexpectedly cut the school year short in the winter of 1988, the thirty-five-year-old made his first trip to the United States, where he quickly found permanent work in New York City.

But six months into his stay, Manhattan life had burned him out, and Sene needed a change. He wanted a smaller city, he told himself, one that was still in the Northeast, but near the water and, perhaps, most importantly, one that placed the self-described jazz obsessive closer to Newport, Rhode Island, and its famous summer music festival. Boston seemed like the best bet, and so, one warm September day, Sene boarded a Greyhound bus and headed there for a week of job-hunting.

A friend had first alerted him to The Andover Shop, a high-end men’s clothing retailer, whose two Massachusetts locations—Cambridge and Andover—had quietly become the epicenter of traditional Ivy League fashion over the previous four decades. Its Harvard Square location needed a part-time tailor. Sene phoned up the shop and was immediately handed off to the store’s owner and cofounder, Charlie Davidson ’48.

“He didn’t waste any time,” Sene recalls. “He says: ‘You’re a tailor, but are you a good one?’ I said, ‘I am the best one.’ I think he might have laughed at that. Then he told me to come in the next day to meet him.”

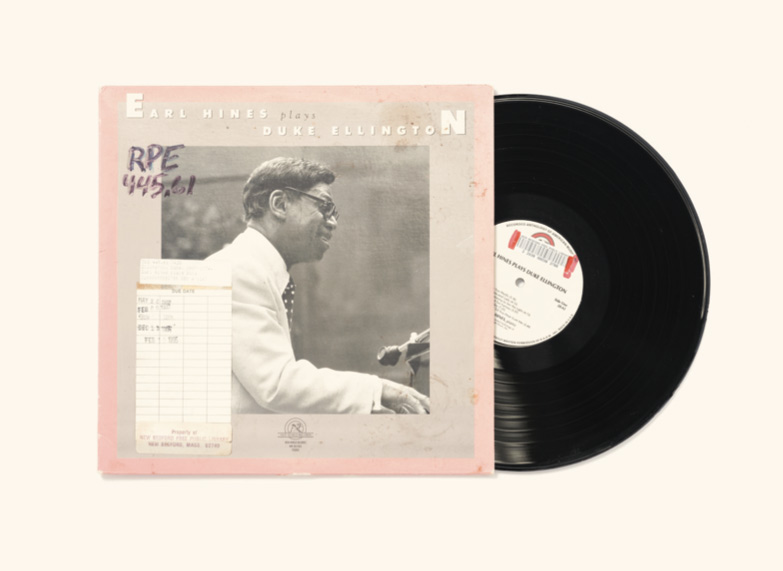

One of many Davidson mix tapes, no doubt including either Chet Baker or Miles Davis—great friends of Davidson’s and jazz trumpeters who were rivals of a sort. Sene says,“It was like being friends with 2Pac and Biggie at the same time.”

What Sene discovered surprised, even confounded, him. For starters, there was the store building itself—a tidy mid-century structure whose gleaming big windows stood in direct contrast to the stuffy brick that surrounded it. Inside, a second-floor tailoring station hummed along, while the main floor was a crowded but meticulous display of jackets, pants, shirts, and ties that resided on racks and shelves.

But it was what lived around the merchandise that caught Sene’s attention: books, records, and art. Many of those items took up space near the front windows, seemingly taking precedence over the actual attire. An obscure John Coltrane song played in the background. Sene thought to himself: What have I walked into?

At the center of this cultural ecosystem was the owner himself. On the surface, Davidson was an unlikely star: He was short—barely five foot two— and spoke in a deep rasp, the result of a bout of cancer that decades before had damaged his vocal cords. He had endured, however, opening for business in 1948, at the age of twenty-two, in his hometown of Andover, Massachusetts.

But it was his Cambridge location, which he’d launched in 1953 in a building he’d designed himself and worked at almost until his death in 2019, that put him on the map. Whether it was intuition or luck, Davidson built his niche around the Ivy League look—the tweed jackets, penny loafers, chinos, and argyle socks—that blossomed in the 1950s. His shop became an epicenter for not just high fashion, but the world around it. The Andover Shop wasn’t so much a store as it was a literary and cultural salon that catered to the owner’s true passions—a hang-out spot for a litany of famous customers-turned-companions that included Chet Baker, Arthur Murray, and Henry Louis Gates Jr. For many decades, Davidson was Miles Davis’s go-to clothing man, and he grew to be close friends with the writer Ralph Ellison.

In a 1967 Boston Globe story, jazz pianist Bobby Short said the Cambridge shop was one of only three places in the world he permitted himself to buy his clothes.

“As a matter of fact,” Short said, “Charlie Davidson at The Andover Shop is working up some new things for me right now.”

This was the unlikely store that Mor Sene walked into that September day in 1988. The young tailor introduced himself and was pointed upstairs, where Davidson sat at a table.

“One of the first things I said was, ‘I like the music playing here,’” Sene says. “He looked right at me and said, ‘Oh, you like jazz—who are some of your favorites?’ I wasn’t sure what to make of him. Who was this little white guy asking me if I like jazz? Maybe I say Miles Davis and he doesn’t even know who he is. I told him, ‘I love Louis Armstrong,’ and Charlie looked at me with these big eyes and said: ‘He is a God. You know that, right? He is an absolute God.’ I don’t know how long we talked, but it was a long time, and all we talked about was jazz.”

Sene got the job, and over the next twenty-five years worked part-time at The Andover Shop. Sene liked the work, but he loved working for Davidson, and as the years passed, the two men grew close. They opened up to each other in ways they didn’t allow for with other people. They celebrated holidays together and shared family celebrations. Davidson, who was the father of four daughters, affectionately referred to Sene as his “son,” while Sene in turn called him “dad.”

“If Charlie liked you, you were in his world, and it didn’t matter where you came from,” says Sene. “He knew clothes, but he knew so much else, and if he was interested in you, there was nothing he wouldn’t do for you. I’ve never met a human being like him before.”

The story of the American Ivy League look is also the story of post-World War II America. For decades, the style had remained cloistered at elite American colleges, propagated by preppy outposts like J. Press, founded on the Yale University campus in 1902. But as the country’s economy roared to life in the late 1940s and the G.I. Bill paved the way for a tidal wave of young American men to go to college, the Ivy League style went mainstream, says Richard Press, former president of his family’s business and grandson of its founder, Jacobi.

“For a time, the booming American economy made it seem as if it were inevitable for everyone to go from No Money to New Money to Old Money,” says Press in the new book Miles, Chet, Ralph, and Charlie, an oral history of Davidson and his shop. “And suddenly everyone wanted to dress this way. It was youthful and cool. A few years later, the jazz musicians gave it a further boost of visibility and cachet and popularity.”

By the 1950s, the market for traditional men’s clothing had exploded, and stores popped up in cities across the country. But Davidson’s shop was always a little different. Foundational to the business Davidson ran were the relationships he formed with his customers. It wasn’t just that Davidson understood the clothes he was selling, says G. Bruce Boyer, longtime friend and former fashion editor at Town & Country—he also understood the people he was selling to.

A blue windowpane jacket, like this one he made for Sene, was Charlie Davidson’s signature look.

“People didn’t come out looking like Charlie,” he says. “They came out looking like themselves. He had these people skills. He was interested in you. He had a genuine joy for meeting people, being with them, and understanding them. You go into any old men’s store and ask for a sport jacket, and maybe he only has one in your size but he’ll put it on you and tell you it looks great. Charlie wasn’t like that. If he didn’t think it was for you, he’d tell you that. He was honest like that, and that really attracted people because they knew they would come out of The Andover Shop looking as good as they could. They weren’t just being sold something.”

For those close to Davidson, his generosity came out in spades. “I can’t tell you how many times Charlie would call up and tell me about this new record that had just come out or this new book that I had to read,” says Boyer. “He was curious about the world and wanted to share it with people. I don’t know who said it, but it’s very true: Charlie had a great gift for friendships.”

But Davidson was particular about the culture he oversaw at The Andover Shop. He famously eschewed trends—Nantucket Reds he found to be especially appalling—and delighted in testing the patience of customers he deemed pushy, obnoxiously monied, or who lacked an understanding of the ethos of his store.

In his 1995 article on bow ties for Atlantic Monthly, writer John Spooner recounts the story of a wealthy businessman who’d ordered three custom-made suits. “Charlie took the order and told the customer they would be ready in ‘about a month,’” writes Spooner. “After five weeks, the customer, whose last name was Zachary, called to inquire after his suits. ‘Not quite yet,’ Charlie said. Another two weeks went by, and Zachary was put off again. Charlie had not made the suits. ‘He’ll get the message,’ Charlie explained. ‘I am not sure I like the cut of his jib.’

Four weeks more, and Zachary called, irate. ‘What the hell do you do over there?’ he asked. ‘Make the clothes alphabetically?’ After hearing this line, Charlie made the suits. Zachary had passed the test.”

For Davidson, the business of men’s fashion offered a constant education, which served the eminently curious storeowner well, says his daughter, Casey Farley. “He learned about clothes as he went along,” she says. “He loved to study it. He was talking to manufacturers all the time. It was all just so personal to him. He wanted people to feel good in their clothes and how they looked in their clothes. You could have a lining in your suit that made it uniquely yours. It would be colorful and hidden, but you knew it was there, so you’d feel bold and you looked good. Those little details were important to him.”

Careful observation was in his DNA. Born in 1926, Davidson was the second of four children born into a tight Armenian American family in Andover, where the elite private school Phillips Andover Academy gave the future clothier a front-row seat to the still nascent American preppy style. His capacity for hard work and affinity for working for himself was learned from his father, Leon, a property developer who early on operated a popular burger joint that local schoolkids affectionately called “Doc’s Place.” Later, he would go on to own and operate the Andover Country Club.

“Our father had us do whatever was needed,” remembers Davidson’s younger brother, John. “Short-order cook, keeping the kitchen clean, emptying boxes of Coca-Cola. He was a fanatic about cleanliness and the freshness of the food. It was always about quality with him.”

Davidson worked for his dad, but he had his eye on another job as well. In a storefront that shared the same building address as his father’s restaurant resided Langrock, a tweedy men's clothier that operated a scattering of shops around the northeast. With his father’s blessing, Davidson left restaurant work and took a part-time job with his father’s tenant, a prime perch for him to educate himself on fashion and building relationships.

“Charlie got exposed to men’s fashion on a quality basis, and it never left him,” says John.

After he graduated from Andover High School in 1944, life took Davidson elsewhere. Across the Pacific, where he served as a belly gunner in WWII; to Brunswick, Maine, where he briefly attended Bowdoin; and to Cambridge to work with J. Press, where, according to legend, he sold a hat to the actor Gregory Peck, which he wore in the 1947 film Gentlemen’s Agreement.

Davidson couldn’t have been too long at Bowdoin, but most of his friends and many of his customers knew of his connection. “He loved Bowdoin!” says Sene. “He tried to get my son to go there.” David Vazdauskas ’82, P’27 says, “When I was in my first year at Harvard Business School, I needed to find a tuxedo for our winter holiday formal. One of my HBS section mates, who had attended Harvard as an undergrad, told me there was only one place to go: The Andover Shop. When we arrived, I discovered my Bowdoin connection with Charlie, and we shared experiences that were several decades apart. He personally outfitted me with my first tuxedo.”

By the late 1940s, Davidson had returned to Andover. Langrock had shuttered, leaving an empty storefront, and Davidson had an idea of how to fill it. In 1948, he and his brother-in-law, Virgil Marson, opened for business. By the mid 1950s, the two men had their respective domains: Marson oversaw the Andover location; Davidson ran the Cambridge store. Business acumen certainly drove the decision to expand, but it wasn’t a coincidence that Davidson landed where he did.

“Harvard Square is the epicenter of the universe,” he once explained. “The whole world goes right by and comes in here.”

That world included artistic luminaries like Davis, Ellison, Baker, and Murray. He outfitted Harvard head honchos, Supreme Court justices, and politicos. When Miles Davis wanted to make a statement at the 1955 Newport Jazz Festival about the new kind of music he was leading, he turned to Davidson to be outfitted. Out went the broad lapels and wide-shouldered jackets the previous generation of band leaders preferred. In came the sleek-fitting suits that Davidson felt best represented the trumpeter. Plus: “I wanted to make sure he looked better than any of the racist [jerks] in the crowd,” Davidson later explained.

Duke Ellington, who was in Davidson’s circle of friends, was known for his incredible sense of style.

In between were all the other lesser-known customers and friends who rounded out Davidson’s life. The accountants, journalists, and professors who came to trust Davidson’s eyes. Constantine Valhouli was one of them, and his longtime admiration of the clothier resulted in Miles, Chet, Ralph, and Charlie. His introduction to Davidson’s world came at the age of ten, when Valhouli’s father took him to The Andover Shop to get a navy blue blazer. Valhouli was a reluctant participant in the transaction, and Davidson sensed it immediately. But rather than rush the exchange through, the shop owner took his time with the boy.

“I get the sense that you’ve always got a book with you,” Davidson said, and encouraged Valhouli to consider a jacket with patch pockets. “A book will fit more easily in here.”

Some four decades later, Valhouli still marvels at the exchange. “I couldn’t tell you if it was incredible salesmanship or incredible empathy, but he pointed this thing out, then took the book I had with me and slipped it into the pocket,” says Valhouli. “He saw me for who I was and what was important to me. It felt exciting.”

Valhouli contends that one of the strengths of Davidson is that he was an insider with an outsider’s perspective. He wasn’t a musician, or a writer, or an academic, but he understood their worlds. And while he made his trade in traditional clothing, Davidson was anything but old-fashioned. He never found his place in formal schooling, had been fiercely determined to work for himself, and in an age when some of the country’s most renowned Black musicians and intellectuals couldn’t secure even a hotel room in Boston, Davidson welcomed them into his shop and home.

“He was famously fiery and cantankerous, but also incredibly loyal,” says Valhouli. “At various points he’d give clothing away to people who really needed it. He was someone you could turn to for advice. If someone was going through a divorce or had a sick child, they knew they could talk to Charlie. He was always there for them, and because of that he created all these connections. If you think about some of his most famous customers—Miles Davis is known for St. Louis and New York; Chet Baker was more of a West Coast performer; and Ralph Ellison is connected to the South. But they all came together in Charlie’s store, and they knew one another because of it.”

“People say how much Harvard Square has changed,” Davidson once said, “but I haven’t noticed. To me nothing’s changed. The ties get wider, then they get narrower—that’s it.”

But that wasn’t completely true. The world got bigger. Tastes evolved. And dress got more casual.

Davidson’s shop, however, held a unique status: It was not only one of the first to usher in the new age of American Ivy style, it also became one of its last. “When I first came to Harvard Square, there were ten good men’s stores, and we all had to divide that clientele up between us,” Davidson explained in his later years. “Today there are only two here: me and J. Press. So, you can take that big pie and cut it in ten, or take a small pie, and cut it in two.”

It endures today. Nearly five years since his passing, Charlie Davidson’s legacy lives on. Certainly, you can find it in the Cambridge store he once presided over. Many of his longtime customers still frequent the place for the tweeds, custom suits, and blue blazers the founder once outfitted them with.

You can also still find it in the work of Mor Sene. Sene struck out on his own in 2014 to open up a tailoring service in Burlington, Massachusetts. But while he left The Andover Shop, he never left Davidson. The two remained in close contact—just a week before his friend passed, Sene and his family celebrated Thanksgiving with Davidson and his partner, Joyce Comfort. On the walls of Sene’s business is the evidence of their friendship. A large photo of Davidson at his store, a framed honor from the City of Cambridge that says “All Hail the King!” as well as cherished posters of Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong that had once been displayed in his friend’s apartment.

Under a row of tables are boxes of books Davidson left Sene. On history, music, and literature—nearly five hundred volumes in all. Elsewhere, Sene has put into storage the more than fifty thousand CDs Davidson collected. What will he do with them all? Sene has a plan.

By early 2025, Sene, who will soon turn seventy, will return to Dakar to live, where he is setting up a new tailoring school. A building has already been secured and is being renovated; soon a lineup of new sewing machines from China will make their way to Senegal. The project gives its founder not just a chance to return home but to give something back to his country. It also allows him the chance to spread the legend of Charlie Davidson a little further. The school’s new library will be named after his old friend, and its collection will largely consist of his books and CDs.

“There are people who want success in life— they want the planes, the big house, and the fancy life,” says Sene. “Charlie was never like that. He was about success for life. He cared about the important things—art, music, and people. He was a special man, and I want others to know about him.”

Ian Aldrich is the deputy editor at Yankee Magazine.

Tristan Spinski is a Maine-based photographer, writer, and filmmaker. He earned his master’s degree in journalism from UC–Berkeley.

This story first appeared in the Summer 2024 issue of Bowdoin Magazine. Manage your subscription and see other stories from the magazine on the Bowdoin Magazine website.