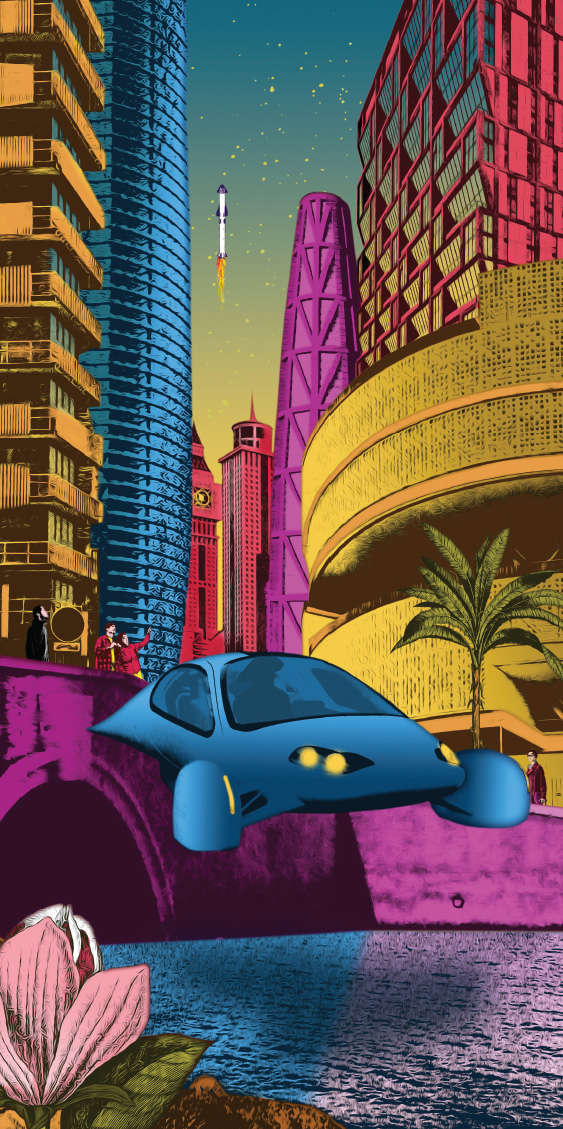

Humanity’s Art

By Michael Colbert ’16 for Bowdoin MagazineSenior lecturer Jill Pearlman calls them “humanity’s greatest achievement.”

A hub for culture and commerce, cities are also places where some of the most intractable problems of society are magnified: poverty and income inequality, traffic congestion and pollution, overcrowding and crime. And yet they continue to be human magnets—experts estimate that even as the world’s population grows, cities will house something like 70 percent of our world’s citizens.

Students in Bowdoin’s new urban studies minor learn to think critically about cities, and alumni work in all kinds of ways to consider challenges and opportunities in the years to come and to reimagine cities—with clarity and optimism.

Thomas Jefferson thought the United States never would—or should—have cities.

“He thought we’d create the raw goods here, ship them to Europe, and let them industrialize, because industry and cities are synonymous. Cities have grown up around industry,” said Jill Pearlman, who codirects Bowdoin’s new urban studies minor along with professors Theo Greene and Rachel Sturman.

Pearlman teaches the history of urbanism and architecture at the College, asking students to interrogate the relationships people develop with their lived environments. Her course, City, Anti-City, Utopia, begins by looking at an idea that persists throughout American history, that our cities must embody the “best of city, best of country.” Circumstances in the US didn’t develop as Jefferson imagined, however.

“Obviously, that didn’t pan out, and we had to do our manufacturing here, so cities—really mill towns—sprung up,” said Pearlman. “Then we see in the city all of the things Jefferson warned us against: we have poverty, we have slums, we have hierarchy, misuse of power. In Jefferson’s case, both themes come together. In the quest for the marriage of perfect city and country, there are a lot of proposed utopian schemes along the way: the garden city, the tower in the park.”

Portland, Maine: A Case Study

Across the College’s various urban thinkers— faculty, students, and alumni alike—there seems to be consensus around cities’ capaciousness, their ability to grow and develop.

“Cities are humanity’s greatest work of art, our greatest creation,” said Pearlman.

“They’re where people come together, communicate with each other, and feed off one another more than anywhere else,” she added. “It’s where our greatest art, architecture—our greatest cultural accomplishments—are created and performed. It’s also the place where we have our biggest flaws, where our biggest crises are magnified.”

Such questions have persisted for centuries. Crime became an important issue for voters around the country in the last election and in many others before that. Half an hour down the road from Bowdoin, Portland often finds itself amid the discourse surrounding cities: ranking as one of U.S. News and World Report’s best cities to live, Bon Appetit’s Restaurant City of the Year, a beloved tourism destination for visitors around the country. The pandemic brought with it an influx of new Mainers—about 55,000 new residents to the entire state, the Portland Press Herald reports—and Portlanders subsequently noticed a spike in the cost of living. As more people struggle with housing, encampments have grown and been the subject of debate and controversy in the city.

Assessing a place like Portland, Theo Greene finds that the very notion of the city starts to unravel.

“As Portland has ascended as a creative location and a destination for tourists, the qualities that sociologists ascribe to cities may shift depending on the time of year,” he said. “In the winter, when there are not a lot of tourists, it has a village-like quality. People know each other. It seems to be that people can access things very easily. Interactions are much more cordial and friendly. Then in summertime, when you have hundreds of thousands, even millions, of people moving through Portland, you have these different dynamics that actually very deeply mirror a city.

“That’s been of really great interest to me in recent years: what makes a city?” he added. “There are some places that very clearly will always be a city—New York, Los Angeles—but what about other places that may not be as large but still can have the forms of urbanism, urban culture, and relationships that might emerge in New York, San Francisco, Los Angeles, or Chicago?”

Cities possess boundless potential. In a place like Portland, with its growth and attendant problems, questions that Pearlman poses bubble to the surface. Who are we building for? What’s the vision of this place? Who even fits within that collective vision, and who’s excluded? How can cities—in all their rich possibilities—accommodate the slew of problems that accompany them today?

Unlocking Urban Solutions

For architect and sustainable cities consultant Peter Steinbrueck ’79, the marriage of city and country finds accord in Seattle’s Pike Place Market.

“Pike Place Market is the densest human interaction you’ll find in Seattle,” he said. “Daily, it’s people brushing shoulders, like the subway in New York City. It’s massive numbers of people thronging in a confined space. You may go there to buy some local fresh produce, or go to a restaurant, but really, the total experience that we enjoy is through that human interaction: sights, senses, smells, all those things.”

While this collision of human life captivated Steinbrueck from an early age, Pike Place’s future was not always so certain. As a child, Steinbrueck partnered with his father and joined the efforts to protect the market when the city nearly bulldozed the landmark. The efforts were successful—the market is a proud icon of Seattle today—and for Steinbrueck its preservation underlines the role that cities play in fostering human connectivity.

“Cities evolved as a place of commerce and trade,” he said. “Going back thousands of years to their earliest formations, they were where people came together for social interaction, which is a human need.”

Taking a wide-angle view on the concept of “the city,” it can seem that conflict resides at its core. But they’re places where people find possibility, where people graft their imagination onto development, arts and culture, skyscrapers. Yet why do they so magnetically attract the imagination?

For Prema Katari Gupta ’00, cities embody significant points of human connection.

“I have always been drawn to places where people can be together,” said Katari Gupta. “I really like the idea of cities as places of celebration, culture, and togetherness. Whether it’s supporting the Eagles or the Phillies, or seeing the ballet, or going to see Taylor Swift, I think cities are places where people get together, which to me is an essential and critical part of being a human.”

Based in Philadelphia, Katari Gupta is CEO of the business improvement district, Center City District, a role that she describes as “downtown’s biggest cheerleader.” This enthusiasm pervades her work, and she identifies solutions to social and environmental problems wrapped up in urban living.

Take public transit, for example. In order to meet global climate goals, Katari Gupta says that countries need to double down on existing modes of transportation.

“I think a lot of people have the perception that living somewhere rural is best for the climate, but the percentage of greenhouse gases that come from automobiles is profound. Having a pattern of life and work where you’re able to rely on public transportation, walking, and bicycles is what’s best for the environment, and cities are where that can happen at scale. I often say two-thirds of jobs downtown don’t require a college degree, but not one of them requires a car.”

The same philosophy bears out across the country. As Los Angeles is looking to build the Sepulveda Transit Corridor, a new subway line, Nick Suarez ’21 provides environmental insight and assesses impact—from noise and vibration impact to air quality and biological and cultural resources. Though Los Angeles may be synonymous with the car, Suarez notes this was not always the case.

“There were a number of streetcar lines along major arterials in Los Angeles in the 1920s and 1930s,” he said. “It’s a pretty new city, compared to others on the East Coast or in Europe, so it was in a unique historical place for development; the city was just getting built at a time when there were these new transportation technologies.”

As the planning ideal reformulated around the automobile, however, the city pivoted to freeways and single-family homes.

“This creates a traffic nightmare. Everything is so spread apart, and everyone’s trying to get to very distant places,” he said. “What LA Metro is trying to do is bring us back to that point where we were before, with a more sustainable system and lessening the environmental impacts of those previous decisions.”

“Cities are definitely the key to environmental resilience,” he added. “If you look at the environmental footprint of someone living in a rural area versus a city, it’s much lower for someone living in a city, because everything is so concentrated. That’s a concept that we try to maximize in urban planning.”

The City as a Work of Art

The city is a meeting point. It is an environment where people come together and exchange ideas, and here art is made.

“Cities are spaces of collaboration,” said Pamela Fletcher, professor of art history. This semester, Fletcher is teaching Art of Urban Life in Europe, 1500–1950.

“Artists travel to different cities in order to see the art there and to learn from the people who are practicing there, but it also gives rise to various kinds of conflict,” said Fletcher. “For example, if you want to understand a lot about Italian Renaissance art or the various political conflicts with the Medici as Florence—the city and the political entity—transitioned through various phases of government, art is a really powerful tool in both the Republican and Medici arguments about who should rule the city, why, and what their values are.”

While students in her course could examine works of art and simply telegraph today’s problems onto the past—seeing where the Medici conflict could shed light on the development of an emerging city like Portland—Fletcher also wants her students to see the art, and the cities it depicts, on its own terms.

Urban life has been artistically generative for centuries. She points to William Hogarth’s paintings of modern moral subjects in the eighteenth century: depicting sheriffs and madams and thieves, he created art for people who live in cities, which captures the feeling of life in London. She thinks, too, of Impressionism and German Expressionism.

“There are these very expressionist pictures of the streets of Berlin that are not about trying to capture the actual cultural geography of it but what, I think, humans have felt in cities for a very long time, which is both energized and overwhelmed by the sheer scale of cities,” she said. “How have artists made art about what it feels like to live in a city, to live in such close contact with people who are unfamiliar? Art is a place where people processed a lot of those feelings.

“At any moment that anyone’s living in a city, their experience of it is often one of change and dislocation,” she added. “On the one hand, you can think of the city as this vertical thing: that land, those places, things, and buildings, all with this rich history. But on the other hand, you get these masses of people moving through at any particular time, and their collaborations and collisions give rise to an emotional life, and that is part of what generates so much art out of city contact.”

Cities are places of wondrous production. Through the collaboration, clashes, and encounters they promote, they provide both the inspiration and the backdrop upon which people can dream.

In Search of Community

A dream of another place became a lodestar for Theo Greene, who studies urban sociology and the role of the gay neighborhood, at the College.

“When I began to do field studies, I understood the powerful role that cities played in terms of the formation of a gay identity,” said Greene. “The notion that the size and density allow people who were exploring sexualities to be anonymous. That led me to really understand the dynamics of the city, and how a lot of the problems and opportunities that exist in cities are deeply interconnected in terms of community, placemaking, movements, and the various kinds of activities and infrastructure that exist there.”

The power of finding community within a larger place resonates with Suarez as well.

“There’s definitely a duality in terms of how people feel about cities,” Suarez said. “A lot of people say you can never really know Los Angeles because there are so many corners of it, and each neighborhood is completely different. I think that goes against what we look for in a home.”

The city’s beloved neighborhoods can at once be alienating and contain within them the potential to help Angelenos form attachment to place. Small institutions help people make sense of a megacity like Los Angeles.

“It’s when I go to the small bookstore and the coffee shop that I feel most like this is where I want to be. It feels like a neighborhood, kind of like Brunswick. It feels like something that’s attainable.”

The scale becomes more human. Suarez argues that’s something planners and stakeholders should strive toward.

“I’ve seen memes on Facebook that say college is the greatest four years of our lives because we actually live in a walkable environment,” he said. “When we think about some of the biggest issues like crime and homelessness, I think that the answer lies somewhere in finding a new sense of community for everybody in a city.”

Making Place Lovable

For many different populations, there’s significant value in like finding like in a city. To respond to Pearlman’s question—who are “we” building for—the paradigm might need to shift.

“Cities that are trying to achieve livability— the standard way to try to be like every other city—can tend to correlate with a negative gentrification and a monoculture,” said Ethan Kent ’98. Kent founded PlacemakingX, an organization that sees public spaces as a means to connect local communities and address a broad range of crises and challenges, from equity to health and isolation.

“Our theory is that you want to preserve and attract lovability—place attachment—and that actually attracts livability in a more inclusive, affordable, and faster way,” he added. Kent sees that conventional means in which cities strive toward livability do not inspire place attachment but generate a consumptive experience, one that’s transitory, more expensive, and often less culturally distinct.

“But leading with social life, with the existing population defining their public spaces and attracting new people—a new investment on their terms—is a more sustainable and inclusive way of allowing a city to develop.”

Kent has worked in numerous cities around the country and the world, training people to create more inclusive public spaces. This led him to establish PlacemakingX in order to connect and support placemaking leadership and projects all over the world.

“In the ’70s, downtowns around the US were very much disinvested in. People were improving public spaces through policing them and making them less friendly and taking out the seating,” said Kent. “The new idea at that time was to invite people in so that public spaces become safer and more inviting for everybody. The theory was that if any one user group dominates a public space, it’s a form of privatization. It’s not about pushing out those groups—it’s inviting in whoever’s not welcome and supporting them, challenging them to be a contributor to the spaces.”

Spending time working on markets, waterfronts, and squares, Kent has found that investing in public spaces can be a way to address not just inclusion and economic development but also social health, cultural creativity, and preservation. Kent points to the example of Detroit; by partnering with the local population first, there’s great potential to build—and attract development—from the ground up.

“People love it because they feel like they’re part of its story. They’re being challenged to contribute to the entrepreneurial and cultural ecosystem there,” said Kent. “It’s almost because of its incompleteness, the porosity and openness, that it’s creating this dynamic narrative that many cities should learn from.

“We led a lot of public space projects that worked with the existing population to lead with programming and activation of spaces in the very short term with low costs. That then attracted billions of dollars of investment in the downtown,” said Kent. “Detroit was one of the emptiest downtowns in the country, even just ten to twenty years ago; now, it’s one of the liveliest. It shows how a city can transform through inclusive, active, public spaces, and attract development that adds to those spaces.”

Reason to Hope

Though the perception of American cities in the media may sometimes be negative, Katari Gupta sees significant reason for hope in cities’ creativity and adaptability. She thinks often of the public realm—everything between buildings, from the sidewalk to the street, trees, and bike lanes.

“For the last ten to fifteen years in American cities—maybe inspired by a desire to make cities more livable—we have seen a reallocation of the public realm,” said Katari Gupta. “That to me is of huge interest because it is what makes cities more livable, more competitive, and more desirable to be in.”

As people adjusted to life during the pandemic, restaurants reclaimed space from the street for outdoor dining.

“You tell me what’s better for the city’s economy: for somebody to park a car [in a spot] all day and maybe pay five or six dollars to the local parking authority, or for it to be eight or ten tables for a restaurant, the tax from that, the people enjoying themselves, the socialization, the jobs created and preserved,” she added. “I think we realized that not only was it a more urbane or more gracious use of the public realm, but that cities benefit, too. It’s been really nice to see a lot of cities hang on to those outdoor dining typologies that maybe didn’t exist before but that we’ve all been enjoying in other countries for a long time.”

Reimagining process seems to undergird the philosophy across the board—who’s brought into the process, who’s allowed to become a stakeholder, and what powers they are given.

“One of the things I see about Portland—and why often I would not associate it as a city—is, even though it’s developing these big urban problems, it doesn’t have the infrastructure to deal with them,” said Greene.

Examining the city’s attitude toward addressing social problems, he pointed to a recent city council decision to lift encampment restrictions during the winter.

“People are not necessarily thinking beyond the immediate problem to understand longterm solutions, and how even short-term solutions have impact in terms of the broader infrastructure of the city,” he said.

“I think that the key for problem-solving in places like Portland is providing opportunities for people to think beyond simply the immediate problem,” he added. “As the population is changing, diversifying, and growing, the inequalities have become far starker. It raises a whole series of issues that leads to people coming up with these short-term solutions that can be harmful to the city’s development.”

Suarez also recognizes the need for a new approach. “I think honestly if we want to solve the big problems that cities face, then it has to be a more interdisciplinary approach.”

Cities hold so much within them: the coin’s two sides contain boundless potential for creation and challenges. It stands to reason that the solutions—and the mindset—we bring to approach them must meet them in their full complexity and from there, begin to dream.

Michael Colbert ’16 is a Portland, Maine–based writer. You can find his work at michaeljcolbert.com.

Pierre-Paul Pariseau is an illustrator based in Montreal who works for a wide range of international clients. Find his work at pierrepaulpariseau.com.

This story first appeared in the Winter 2024 issue of Bowdoin Magazine. Manage your subscription and see other stories from the magazine on the Bowdoin Magazine website.