The Very Spot

By Rebecca Goldfine for Bowdoin MagazineOver the summer, Aggie Macy ’24 and Lillian Frank ’25 traced northerly routes that explorer Donald MacMillan took at different times a century ago, up the coasts of Labrador and Greenland.

Their journeys put one of them on the same ship deck as MacMillan and the other searching for the exact places where he had put his feet and trying to replicate the angle of his camera. In the course of their journeys, they would not just discover and learn for themselves. The work was funded by grants from Bowdoin, provided by donors, and it would itself be a gift—to Greenlandic communities, to Bowdoin’s Peary-MacMillan Arctic Museum, and to the scholars themselves.

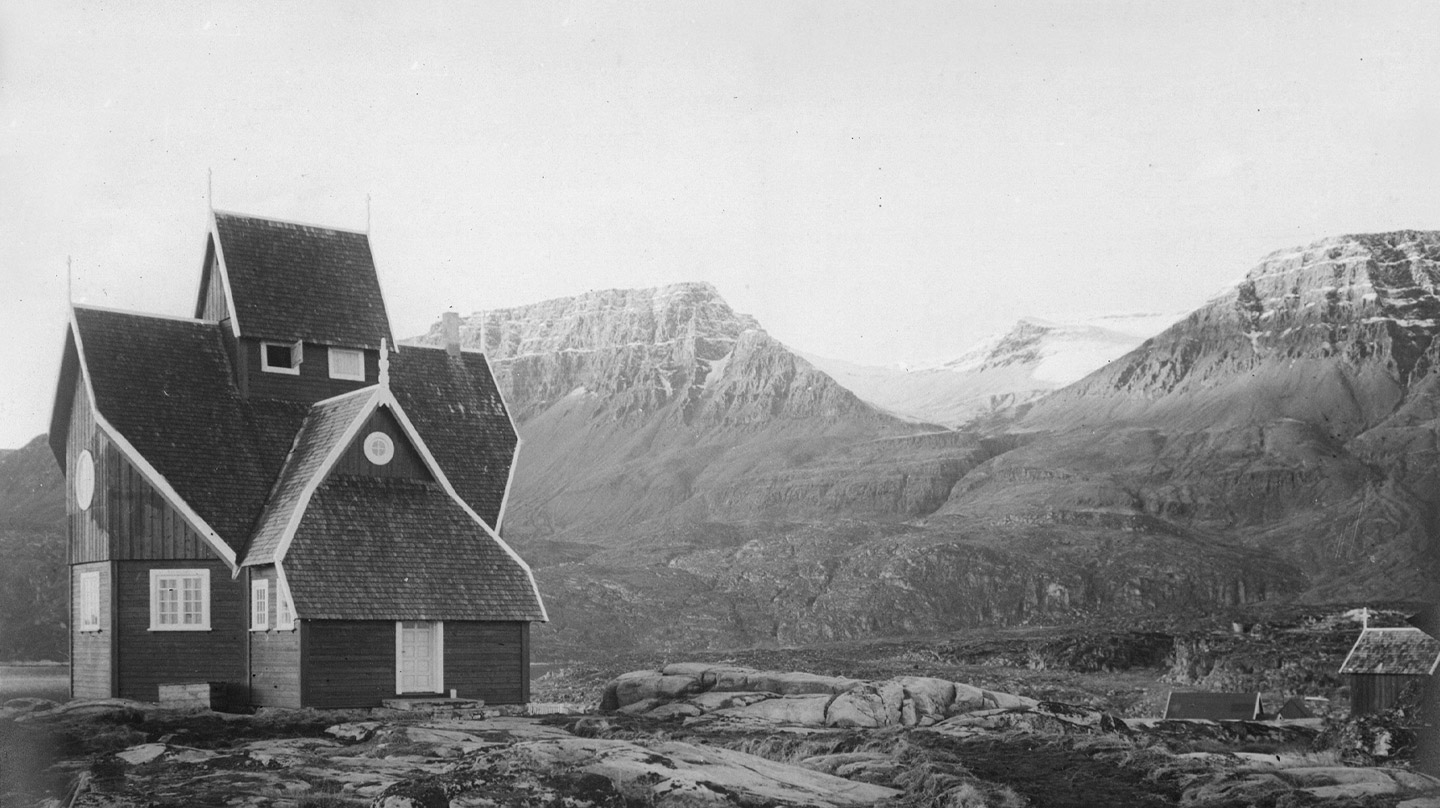

Battle Harbour, Labrador. Part of Canada’s National Historic Trust, Battle Harbour is preserved as a complete settlement.

The stirrings that would lead to Aggie Macy’s voyage up the coasts of Labrador and Greenland began last year, in the summer of 2022, when she was hired by the Peary-MacMillan Arctic Museum to research one of its old maps of Greenland.

The 39.5-inch-by-23.25-inch map, now timeworn and colored the hue of well-steeped tea, was hand-drawn on waxed linen in 1917 by Illinois-born geologist and botanist Walter Ekblaw. He had sketched it at a doctor’s home in Greenland while recuperating from frostbite at the end of a perilous four-year Arctic expedition, led by MacMillan, in search of the mythical Crocker Land. In his neat, slanted script, Ekblaw had written the Inuktitut names for the region’s geological features, settlements, and waterways.

The museum staff wanted to make the rare item more accessible to its visitors, so they asked Macy, an accomplished Arctic studies student, to learn more about the descriptions and translate them to English. “The names are full of meaning,” Curator Genny LeMoine said. “They’re sometimes physically descriptive. Sometimes they describe what people did or do there, or the animal hunted there. Or they describe a historical event.”

To aid the translation, Macy scoured other old maps of Greenland and cross-referenced their toponyms with MacMillan’s 1943 dictionary, Eskimo Place Names: An Aid to Conversation. MacMillan was a Bowdoin graduate from the Class of 1898 who repeatedly traveled to the Arctic over his adventurous forty-six-year career, becoming a sought-after expert on the region and its people.

At the end of her internship, Macy had created an interactive interface of Ekblaw’s map for a museum exhibit that lets visitors scroll through the region using the poetry of Inuit place names as their guide. All that work—and all that poetry—led to an abiding desire to see these places for herself, in person.

Masts, lines, and sails of the schooner Bowdoin. Photo by Lillian Frank ’25.

Lillian Frank’s journey north began with an email last spring from Macy, who is one of her best friends at Bowdoin. Macy found out from the Arctic Studies Program that there was an opening on the two-masted schooner Bowdoin—MacMillan’s own ship—to sail up the coast of Labrador. The captain was inquiring whether any Bowdoin students would be interested in joining his Maine Maritime Academy crew for the six-week summer trip.

“She forwarded the email to me and said, ‘You should do this; it is everything you like to do,’” Frank recalled—that is, be immersed in history, travel, sail, and discover. Frank, a visual arts minor, was also taking a photography class that semester, and she wondered if she could turn the trip into a photo project. So she applied for and was awarded a Koelln Fund mini-grant from the College to record her impressions of the journey through photographs.

In her project proposal, Frank notes that she would “be one of the first Bowdoin students to return to this region on the Bowdoin since 1954.… I am committing myself to a journey upon the same vessel that MacMillan once sailed, continuing Bowdoin’s long history of connection to the Arctic. In doing so, I hope to form a deep connection with the land.”

Macy was excited by Frank’s proposal to incorporate photography into her trip because she too was planning a photo-based Arctic journey and had received a fellowship to support it. She had proposed a project to her advisors where she would retrace one of MacMillan’s expeditions up the coast of western Greenland and restage the exact images he took. In this way, she would create a record of all that has changed and all that has stayed the same in the nearly one hundred years that have lapsed between the two journeyers. “She was going literally to the very spots he had stood,” LeMoine marveled.

“Service will be questionable, wildlife is plentiful, the swell at times doubtful, and the food less than bountiful. But here I am, optimistic and ready for whatever this way comes.”

—From Lillian Frank's journal, June 9, 2023

Using a map of Greenland scrawled over in pencil by MacMillan, Macy plotted her itinerary, with visits to Ilulissat, which, according to her translation, means “icebergs”; Disko Island (“the big island”); Aasiaat (“spiders”); Sisimiut (“the place with fox dens”); and Kangerlussuaq (“the large fjord”). MacMillan’s 1926 Greenland trip was one of his more comfortable and leisurely excursions. He traveled with twenty-three others, including wealthy tourists, his ship hands, and a taxidermist. He and his party took hundreds of photographs and short films—including hand-tinted glass lantern slides—of everyday activities in the communities they visited: men fishing from kayaks and fileting their catch, women working at a newly opened canning factory, villagers performing traditional dances. Some of the photos depict women in beaded collars and wearing beautifully tailored clothing.

All of these images are in the Peary-MacMillan Arctic Museum’s collections. When Macy was preparing for her summer trip to Greenland, she packed camping gear and many layers of warm clothing in a sturdy backpack to rough it for four weeks on snow and ice. She also downloaded onto her iPad many digital scans from the MacMillan archive to use as reference.

Once Macy had convinced Frank to make her own Arctic journey, she asked her if she could also try to re-create MacMillan’s photos of Labrador as she sailed north along its shore? Frank agreed.

“I met Agnes last year, and we became close quickly,” Frank said. “She’s brilliant. She’s naturally smart but works hard all the time. She has done an insane amount of research and background work and is healthily obsessed with all this history, particularly around Greenland.” But Frank, who only found out she was going on the Labrador sailing trip three weeks before, didn’t have much time to study up and prepare. She also downloaded MacMillan’s Labrador photos on her phone but didn’t look at them a lot. She reflected on what she wanted out of her trip.

Growing up in Maine, Frank says she has a “very healthy relationship with land and what it means to be on land and what a gift it is to be on this earth. So what I wanted to focus on was how I was going to foster my connections with this place.”

As it turned out, even more important to Macy than taking her comparison photos was her wish to share MacMillan’s images with Greenlanders. She suspected—rightly, it turned out—that most local people had never seen his photographs and films.

As soon as she arrived in Ilulissat, her first stop in Greenland, she made an appointment to meet the local museum director, to tell him about her project and show him her iPad galleries. She also began posting the images to Facebook. Within hours, people were commenting in Greenlandic, supplying names of ancestors and other people they recognized. The posts eventually reached a university scholar in Greenland who offered his translating services to Macy.

“I was able to share pictures with captions in Greenlandic and English, and people were commenting, ‘Oh, this is my grandmother!’” Macy said. “That is pretty amazing, because MacMillan took the pictures, but he didn’t collect the names of the people in them.” Macy will use the information she’s learned to add metadata to the Arctic museum’s photo archive.

“In this way, my project felt really meaningful, because there was a reciprocity to what I was doing,” she continued. “I wasn’t just taking photos for myself. I was also giving the community access to them.”

At every stop of her trip, Macy reached out to local museum staff who instantly recognized the value of her offering. In Sisimiut, a small city situated at the end of one of Greenland’s many ice-carved peninsulas, she emailed Dorthe Katrine Olsen, director of the Sisimiut & Kangerlussuaq Museum. “She responded in twenty minutes,” Macy said, and “invited me to come that day.” When Macy arrived at the museum, she settled in with Olsen to swipe through her gallery. “Dorthe was excited by all of them; I could tell there was urgency in her wanting the pictures for herself and her community. She wanted me to share them on the museum’s Facebook page immediately,” Macy said.

Then Macy clicked open a film taken by MacMillan of a welcome celebration in an Inuit village. “We were watching it, and there were pictures of women dancing, and she couldn’t take her eyes off the screen,” Macy recalled.

“She exclaimed, ‘They could be my ancestors!’” The video also includes footage of a small village, now long gone. When Olsen saw this, “she gasped and said she’s never seen this village on film. She kept rewinding it over and over.” The village’s name was Narswangwak, or “grassy plain,” and it was once located in an area in front of the museum, today the site of a hotel. When the hotel proposed an expansion several years ago, Olsen was able to stall the development for three years, long enough to do archaeological excavations. But she had never seen any images of the town she was trying to re-create through its remains. Macy worked with LeMoine to give Olsen access to the photos and videos.

“It turned into a dream of a trip,” LeMoine said. “Aggie made great connections with curators and with museums that our museum has not had direct contact with, as well as colleagues we’ve had for many years. This will lead to more intensive collaborations with museums in Greenland.”

Frank took two cameras with her. One was a digital Nikon camera, about twenty years old, that belonged to her grandfather who passed away two years ago. She learned how to use its manual settings on the trip, taking photos of creamy-looking icebergs 175 feet tall, a solitary boat anchored in a harbor at night, the ship’s captain silhouetted by the setting sun. She also brought a black-and-white film camera, with a plan to develop the negatives in Bowdoin’s darkrooms when she was back on campus. But she ran out of time before departing for her study-away semester in Botswana. “When I look at them later and develop them, I will

learn so much more about the trip and about myself and what I was seeing that I didn’t realize at the time,” she said. “That is a gift, and a gift for me … so I can experience it all over again.”

As promised, she also took as many comparison photos as she could for Macy’s project before the ship hit sea ice and had to turn around, cutting short its original plan to sail as far north as Nain.

![Taken by Donald MacMillan in Qeqertarsuaq in 1926, this photograph was titled by MacMillan Eskimo [Kalaallit] women and young girls.](../images/very-spot-macmillan-1926.jpg)

women and young girls.

Frank said the trip this summer was healing, especially after some stressful times at college. “At sea, you spin around. It makes me feel that I am a small part of this beautiful thing. I feel so lucky to be part of it.” And she said she is grateful to have had the chance to become part of the history of the Bowdoin, which MacMillan had specially designed and built to withstand the ice and storms of the Arctic.

“Bowdoin, the ship, has a heart to it,” Frank continued. “It has been used by students since the beginning, for science since the beginning, and that is a big part of what our trip was about. Bowdoin has always been used to teach, to foster learning, to show people on it a new part of world, and you can feel that when you’re on deck, that there are spirits there.”

Macy said she’s long loved maps, a predilection she thinks was instilled by backpacking and hiking with her family in Oregon’s Cascade Mountains. “I became fascinated with maps and route-planning, and the idea that my ancestors before me walked the same trails and routes,” she said. Her specific interest in the Arctic was piqued by an earth and oceanographic studies class with Collin Roesler she took in 2022 called Poles Apart: Exploration of Earth’s High Latitudes. From there on out, she focused many of her class essays and assignments, for all sorts of courses, on Arctic subjects.

Reading and studying MacMillan’s journals, maps, and photographs, she developed an affinity for the intrepid Arctic explorer. As she and her companion, Caleb McDaniels ’25, traveled from place to place in Greenland this summer—by ferry and on foot, camping each night—Macy kept her own ethnographic journal, as MacMillan did, and restaged as many of his photos as she could. In some places, she found very little had changed. In other spots, she had to crisscross the area back and forth repeatedly, trying to figure out exactly where MacMillan was when he framed his shot. At times she had to give up, daunted by new development that had sprung up in his former field of vision.

But she was often successful. “Many of the original buildings were there,” she said. And the natural features—the ridge lines of hills and craggy formations that she used to situate herself—remain unchanged. “I really did feel like I was retracing MacMillan’s footsteps, actually trying to stand exactly where he stood, and that felt really powerful and meaningful to me,” Macy reflected.

“Obviously, there were so many places around Bowdoin where he stood, but to go all the way to Greenland, I felt very connected to him.”

Rebecca Goldfine, senior writer, works in the communications office doing research, writing, editing, photography, and video for the College. Banner photo by Lillian Frank ’25.

This story first appeared in the Fall 2023 issue of Bowdoin Magazine. Manage your subscription and see other stories from the magazine on the Bowdoin Magazine website.