Wired for Learning

By Michael Colbert ’16 for Bowdoin MagazineWilliam Electric Black ’74 uses lessons he learned at Sesame Street to spark knowledge in kids that just might save their lives.

Ian Ellis James has been electric for years.

Lightning bolt earrings dangle from both ears. His ideas cast shockwaves around the room when he speaks. He can't sit still and at any moment has five different projects he wants to develop. Coming up in the 1970s, he declared it in his name, christening himself William Electric Black. He chose William for his beloved Shakespeare, his literary hero. He selected Black for the period's Black is Beautiful movement, and Electric because it's "cosmic," something else.

Around the dramatic writing department office at New York University's Tisch School of the Arts where he now teachers and we met to talk about his work, James is known solely as Electric. He brings to campus—to faculty meetings and his classes—the energy and inspiration from his long career in the arts, studded with seven Emmys for his writing on Sesame Street from 1992 to 2002. He's written for Nickelodeon and produced shows at experimental theaters around New York City.

Born in Oyster Bay, New York, Electric went to Bowdoin in the 1970s with different ambitions: he was going to study economics. Yet, as he applied himself to the ideas of microeconomics and sunk cost, he felt a pull back to the characters he’d loved becoming throughout high school, while performing in summer stock theater. Because the College did not have the robust theater program and arts and performance community it does today, he felt he needed to transfer, first enrolling at Nassau Community College in his native New York before completing a four-year drama program at Brockport State College.

He quickly made a name for himself there. The school had a strong theater department, and he began to direct, write, and produce his own material. After years performing, he was amazed to see other people bringing his worlds—and the characters from inside his head—to life. When the department chair invited him to come along to a graduate program at Southern Illinois University for playwriting, he moved to Carbondale. There, he found immense pleasure in creating worlds of his own on stage. He started the Blacks Open Laboratory Theater—similarly electric, nicknamed BOLT—out of the student center and put on a couple of plays in Chicago. One thing led to another, and he was asked to start a theater company in Carbondale. Yet, as his classmates moved to Los Angeles and other places, he felt a pull back to his home state.

When he returned to New York, he got involved with La MaMa Experimental Theater Club, an innovative theater on 4th Street, founded by the late Ellen Stewart in the 1960s. In its mission, the theater recognizes the role audiences can play in the formation of art, and it sees the power of art as a force for change.

“I realized what I had taught myself was to really produce my own work. That was the journey, and I really had that skill,” says Electric. “So when I came back to New York, I didn't have to wait and hand somebody a script. I had a space.”

He began producing plays at both La MaMa and Theater for the New City, where just this spring he staged a production of Romeo and Juliet: Tribal Rock Musical, in which he set the words of his favorite bard to rock, rap, pop, soul, blues, and gospel. Before Stewart passed away, she gave Electric a corner of the theater to produce his work and spoken word poetry.

His training in theater ultimately brought him to Sesame Street. He got his feet wet writing scripts, telling stories about how Zoe wanted a pet or how Baby Bear needed a break from playtime with Big Bird. Through his persistence, he got the chance to do what he was really excited about: write music for the show. He worked with the late Gail Sky King and wrote the “Gospel Alphabet” for Patti Labelle and “The Letter O” for Queen Latifah. He even had The Count send up Elvis as The King of Counting.

“I’ve always loved music. Everyone knows it’s so powerful. It can be fabulous especially in terms of working with kids,” he says. “You have music, you have puppets, you’re singing, you have something else to offer to the kids. You’re not dumbing down to them.

“Sesame Street and these other shows are helping kids deal with these emotions that a lot of times they can’t verbalize. That’s a home run.”

One of the key lessons he took from the show was how much planning and research a season required. The work was arduous. Marrying a curriculum to various storylines, he felt like he was in graduate school all over again. In his office, he still has a series of fat, coil-bound research guides: African American Research 1992, Asian American Research Guide 1993. Through the research and collaboration of several people, the writers sought to understand what they knew and identify their blind spots. To offer kids such a robust and culturally engaged education, to help them learn and understand everything from the alphabet to counting, conflict resolution to the trials of the world they’re living in, he says, requires a true ensemble effort.

As much as he’s known in the theater world by his mononym, Electric has become famous for something else too, what he now describes as his “white whale.” Since 2012, he’s been using his writing acumen and love of experimental and participatory theater to address a burning issue: gun violence.

In 2020, gun violence surpassed automobile accidents as the leading cause of death in children in the United States. The New York Times Magazine reported that, as of December 2022, the “gun-death rate for children is nearly five in every 100,000.” Approximately two-thirds of those deaths have been homicides, mostly involving Black children, “who make up a small share of all children but shoulder the burden of gun violence more than any others, a disparity that is growing sharply.”

Throughout his career, Electric has worked to engage his audiences in storytelling and learning through theater and music. Believing that the government was not going to enact meaningful change, he turned to what he knew best: participatory theater. This work began with his series Gunplays, a collection of five plays that approach violence in the city from different angles.

In The Death of a Black Man (A Walk By), Electric thrust the audience into the position of a community in the wake of a shooting. Seats were removed from the theater, and the audience gathered behind police rope, passing through a scene with bullet casings littering the floor.

“I’ve been on this journey. The creative journey has been great. And, you know, sometimes it’s not just about that.”

“They were asking, ‘Did you see anything?’ ‘Do you know anybody—the shooter—that stood out?’ I had news crews coming in with cameras,” says Electric. “And they started to talk about the shooting. I walked the audience around to different sites of the shooting. Then I made a church scene. I rolled in pews, and they sat, and I rolled in a coffin. I took them through the whole experience of a shooting in the community.”

Handed candles, the audience members walked to the steps of the victim’s house, where they laid their candles and the boy’s mother appeared. A crew of twenty worked their magic to transform the theater around them. “A live wire of outrage runs through almost every moment” of the play, wrote The New York Times in its review.

In The Faculty Room, Electric brings the issue to a school, where James Baldwin High School goes into lockdown after a rivalry between two girls on the basketball team escalates and one brings a gun to school. His plays have garnered reviews from The New York Times and NPR, and the collection is being compiled into a book, Gunplays: Five Plays on Inner City Violence and Guns, to be published by Applause this fall.

“After I finished those plays, gun violence and control were worse than ever,” says Electric. “Because I worked for Sesame Street for ten years and for Nickelodeon, I started to think, ‘We really need to do something for kids and get them aware––prevention, awareness—what can I do à la Sesame Street?’

“If the kids are dying, it’s the kids who have to learn how to protect themselves and save themselves. That’s what I’m trying to do; if I teach a kid, we don’t have to depend on somebody going, ‘Well, you know, AR-15s, we’re raising age...’ Hello! That’s not going to save those nine-year-olds. Something else has to happen. If I get these kids on board from an early age, and they learn that guns ruin a family or community, if I can instill that in a kid when they’re four or five, it’ll stick with them.”

Marrying the kinds of stories he’d been telling with his training from children’s TV, Electric piloted a program that uses the arts to educate children on the dangers of guns. He has partnered with several groups throughout New York: the Lower Eastside Girls Club on 8th Street, Avenue D. At PS155 in East Harlem, he got Chauncey Parker of the New York Police Department on board.

Initially, some parents and community members responded to his project with skepticism, saying that children were too young. Yet Electric could see that gun violence was so prevalent that children were already aware of it around them. A colleague of his was walking with his child, who asked him why there were candles and photos clustered on the sidewalk. Middle-schoolers come to school with guns in their backpacks. A six-year-old recently shot his teacher in Virginia.

Kids are perceptive. Rather than call lockdowns “stranger danger” drills, Electric wants to meet kids where they are and speak to them honestly about what he knows they’re seeing.

To open the door, he uses the tools he found so effective through his career in television: storytelling and songs. He puts dreads and a little outfit on his index finger, and his voice rises to the screech of a Muppet. At the end of a recent school visit, students were begging their teacher to let Mr. Finger stay. He adapts songs familiar to kids, “Row, Row, Row Your Boat” and “The Itsy Bitsy Spider,” to teach them that a gun is not fun. He goes through what items belong in a backpack. He hopes that, after a day singing in school, students will bring those lessons home, and the message will osmose into the community—to younger siblings and friends. His colleague at the Lower Eastside Girls Club told him that they sang his songs the whole trip home. Electric’s hope is that when, years later, these children are confronted with the reality he knows is increasingly prevalent, they’ll be more likely to remember that Electric man who visited their school and sang with them.

“It’s natural,” he says. “People want to be part of something. If it’s devised and set up that way, where there is this sort of give and take, you’re not just the audience, you’re going to participate and be on board with it. And you’re gonna sing along.”

Just as Sesame Street collapses the distance between its cast and its audience, Electric wants to be there with kids in schools. This work builds off an old tradition, the Bread and Puppet Theater, a troop of performers established in New York’s Lower East Side in the 1960s. German emigrant Peter Schumann—a sculptor, dancer, and baker—made sourdough bread, which the audience would eat during weekly performances. Through food and engaging theater, the company politically organized against the war in Vietnam, and was a center of the ’60s counterculture.

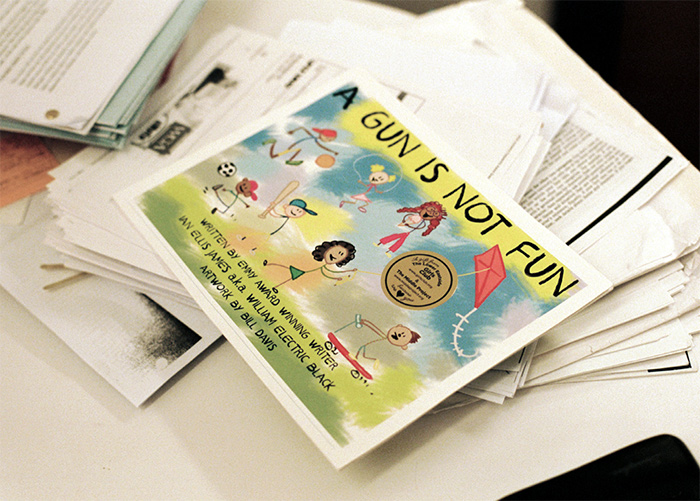

With Gunplays, Electric ended performances with talkbacks following the show, in order for the audience to discuss the material, and he continually adapted the script to reference current events. In The Faculty Room, one of the characters writes an essay imagining a world with Trayvon Martin and the children from Sandy Hook. Talkbacks provided an important moment for dialogue on the play’s commentary and the current state of affairs. Whether through Gunplays, “The Letter O,” or his children’s book A Gun Is Not Fun, the arts— books and songs and puppetry—give people an entryway for conversations. “They open up conversations about things that kids want to do or conflict that kids are dealing with,” he says.

At his last school visit, he brought along a full team to engage the audience.

“I had a piano player. I had a mime artist come in and mime out things: if they see a gun, what do they do. And I had Mr. Finger, and we’re singing the songs, and we’re look- ing at books. Parents and teachers ask, ‘Can this really work?’ I’ve done it so many times. They’re talking about gun violence, and they get it and understand it. I always knew if you find the right way in using techniques of children’s TV, they’ll be with you.”

He aims to replicate the collaborative spirit of Sesame Street and scale the project. The research involved with Sesame Street sought out parents, asking what they needed, whether support with counting or bedtime routines. With such apparent need for action to prevent gun violence, he wants to continue this in his own work today.

“It’s got to be a think tank. I want to bring different people together,” he says. “You can’t do it by yourself. If I learned anything from Sesame Street, you need the community involved. You need certain scholars involved, childhood educators, the gun violence community, people that have been trying to do things, the violence interrupters, or people who are aware of addiction.”

With funding, he would like to develop the project’s research component to see how theater and education can transform communities. He wants to return to schools every year, building out a curriculum that stays with kids. His dream is to give one million kids backpacks emblazoned with “A gun is not fun,” so that when they reach middle and high school, those lessons will resonate with them.

Combing through Electric’s work, I can see him in the architecture of my childhood––from Sesame Street to Puzzle Place. When I think back on my childhood in the ’90s, I can’t help but see the connections to Electric’s work today. What if gun violence prevention were as prevalent in schools as the “Got Milk?” campaign once was? Those ads had me drinking milk like it was my civic duty to support the dairy industry. I knew from preschool not to play with matches. Those messages stick. What could happen if kids passed by a poster saying “A Gun Is Not Fun” every day in their cafeteria?

Though he transferred from Bowdoin, Electric stayed in touch with his friends from the College. While his time as a student in Brunswick was short, he saw “the Bowdoin guys were fabulous.” When Kenneth I. Chenault ’73, H’96 was awarded The Bowdoin Prize in New York City last fall, Electric attended the ceremony.

“They rocked it, and I rocked it in another way,” he says.

He wants kids to see how they rock it too. If a twelve-year-old can pick up a gun and think to use it against another child, he sees that the problem runs deeper. He wants to emphasize the value of the lives of the people around them.

“They’re pretty pure, but kids go through a lot, and sometimes they don’t have the words to express what they’ve gone through,” he says. “I’ve found that Sesame Street and these other shows are very smart about trying to get in there with the kid on their level, to help the kid figure out those emotions, to help a kid stop and think first.

“I’ve been on this journey. The creative journey has been great. And, you know, sometimes it’s not just about that; it’s not just about loving Hollywood or being on the road. Something else calls you to do something. Some of my friends go, ‘Man, you’ve been on that gun violence thing for a long time. You kind of knew.’ It’s not a good thing. I just felt, you know, kids are dying. People have died. What is that? It breaks my heart.”

Human value is as important in messaging as it is in the artistic process. Electric was awed by his peers on TV. He saw magic in the puppeteers’ work, bringing his favorites like Cookie Monster and Oscar the Grouch to life. His family––his wife, Lucille, and three daughters––have been in his corner, cheering him on at his shows over the years.

Still today, Electric is chasing something—that white whale. Having seen the impact made by the puppeteers he has collaborated with for decades, he wants to turn Moby Dick into a puppet. Contorting his hands, he animates the motion. Puppeteers rise from a swell of the ocean and animate a massive sperm whale, Melville’s obsession and a representation of Electric’s. He rises with a majestic flourish of fabric and looms over the stage.

With a whoosh, it disperses.

We can feel the electricity leave the room.

Michael Colbert ’16 is a Portland, Maine–based writer. You can find his work at michaeljcolbert.com.

Levi Walton is a photographer and director in Brooklyn, NY. His work has been featured in Vanity Fair, Cosmopolitan, Rolling Stone, Dazed Magazine, and other publications. See more from him at levi-walton.com.

This story first appeared in the Spring/Summer 2023 issue of Bowdoin Magazine. Manage your subscription and see other stories from the magazine on the Bowdoin Magazine website.