Bringing History to Life

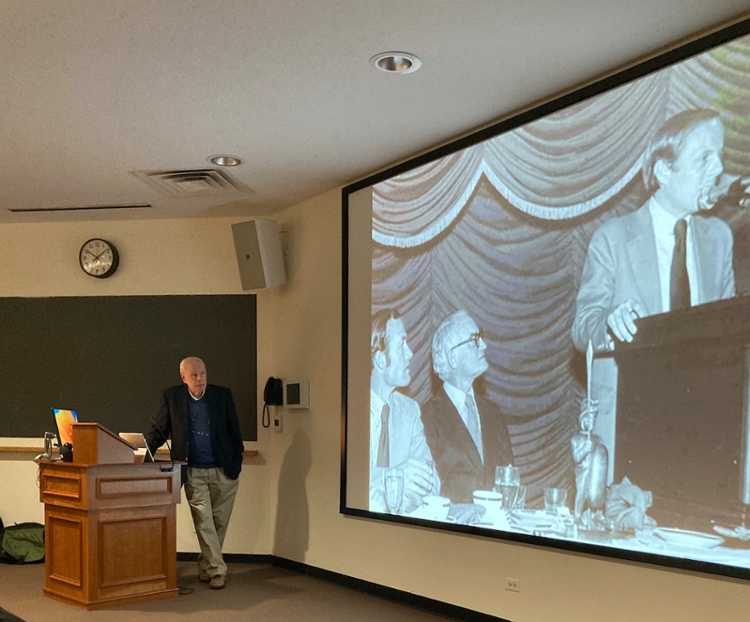

By Tom PorterDean was an honored guest on the Bowdoin campus for two days in early May, during which he took part in a conversation with the Bowdoin community. He also spoke with students from Thomas Brackett Reed Professor of Government Andrew Rudalevige’s class, Watergate and American Politics (GOV 2001).

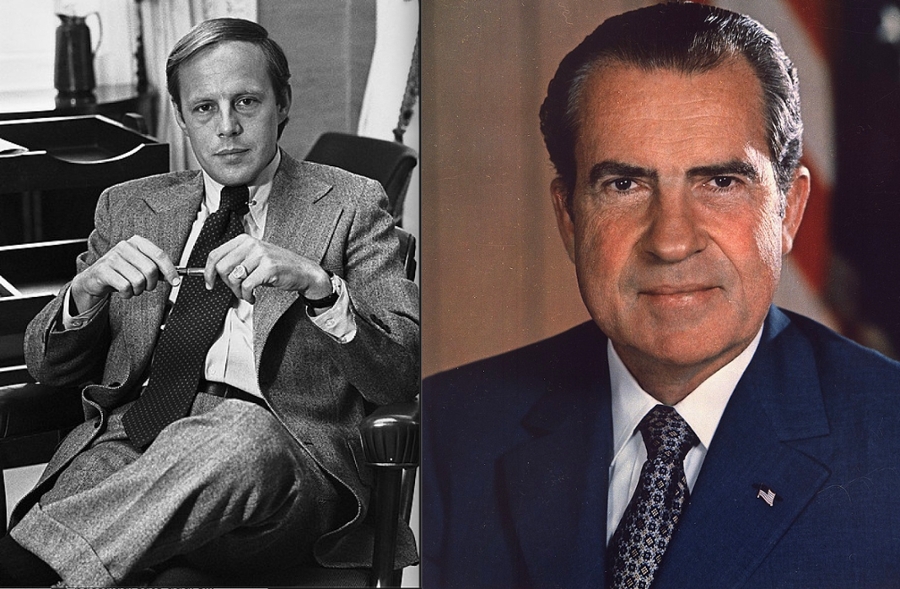

In April 1973, nearly three years into his job as counsel to Republican US president Richard Nixon and still only thirty-four years old, Dean was at the center of an unfolding and unprecedented political drama.

In an attempt to distance himself from the Watergate scandal—which detailed the administration’s involvement in two 1972 burglaries at the Democratic National Committee headquarters in Washington, DC’s, Watergate building—Nixon fired Dean, forced the resignation of his two highest-ranking and most trusted aides, H. R. Haldeman and John Ehrlichman, and replaced his attorney general, Richard Kleindienst.

When he first learned about the break-ins—following the arrest of the burglars during their second attempt in June 1972—Dean found himself caught up in the scandal as he played a key role in covering up the affair.

To make matters more complicated, and more scandalous, the Watergate break-ins also brought to light the government’s covert involvement in another botched burglary in California the previous year. This was part of an effort to discredit the person who leaked the classified Pentagon Papers, which contained damaging revelations about US policies in the Vietnam War.

“When do I realize what we’re doing is insane?” reflected Dean, addressing the students. By mid-March, 1973, recalled Dean, he was plagued by serious doubts and realized that huge mistakes were being made that could land him, and others, in jail. “What drew me out of it is reality,” he said.

Dean decided to confront Nixon on the issue, telling him there was “a cancer on the presidency.” During the near two-hour conversation that followed, Dean, who in the years since Watergate has been an author, a commentator, and an investment banker, said it became clear to him that Nixon was not interested in confronting or admitting to the problem. Nixon said this conversation with Dean was the first time he learned about the cover-up—an “absurd” claim, said Dean, which was later proved to be untrue.

Dean, who correctly surmised that key White House figures were planning to make him a scapegoat, ended up testifying before Congress, detailing the extent of the cover-up and acknowledging his role in it, for which he served a four month sentence. His riveting testimony, which drew record television audiences, was backed up by the revelation of the White House tapes (secretly recorded by Nixon) in July and ultimately proved the president to be a liar.

Calls for Nixon’s impeachment were amplified in October 1973 following the so-called Saturday Night Massacre, when the president fired special prosecutor Archibald Cox, prompting the resignation of high-level Justice Department officials as well. The House voted to officially begin an impeachment inquiry in February 1974. Later that year, in a landmark decision, the US Supreme Court unanimously ordered Nixon to hand over all tape recordings and other materials related to Watergate. In August 1974, Nixon resigned as president.

Dean said part of what made him want to expose the cover-up was the fact that he was “not someone who follows orders easily. I can't, as some of my colleagues did, just click my heels and salute.” In the five decades since the event, he added, the Watergate scandal and its implications have more or less dominated his life. Furthermore, he has learned a lot more about the event since it happened than he knew at the time, he explained.

Accompanying Dean on his visit to Bowdoin was Timothy Naftali, historian and former director of the Nixon Presidential Library and Museum. What makes this episode so important, he said, “is that for the first time in American history it looked like it was possible that a US presidential administration could collapse.” As director, Naftali oversaw the transition of the Nixon Library into the National Archives system and corrected its notoriously misleading Watergate exhibit.

Addressing the students, he drew attention to the enormous amount of information now available to historians thanks to the hundreds of hours of tapes that have been released of conversations that Nixon had with his administration officials, his staff, and his family. “The archives are being updated constantly,” he said, “and the opportunity to write a book about Nixon is extraordinary now...The amount that’s come out in last twenty years is incredible,” he enthused, “a lot of it absolutely untouched.”

Class reaction: “The events of Watergate and their cover-up are so unbelievable in their disregard for the law that it was surreal to talk with a major player in person,” said Lexi Ashraf ’24. “The most insightful aspect,” she added, “was hearing him reflect on how he got caught up in the cover-up, how the pressures of the administration made it seem like the best option when retrospectively it was clearly morally dubious.”

“The John Dean visit was an amazing way to wrap up the semester and bring the course material to life,” observed Spencer Sussman ’25. One particularly memorable moment, he said, was when Dean recalled how President Nixon usually had both feet casually up on his desk during conversations in the oval office. “But when Dean famously warned him of the 'cancer on the presidency' (a tape we listened to many times in class), Nixon firmly planted both feet on the ground. This type of remarkable first-person detail helped me visualize the White House tapes we spent so much time studying and helped to humanize the major players of the Watergate scandal.”

“’Watergate and American Politics’ is one of my favorite courses to teach precisely because it brings history to life,” said Professor Rudalevige, whose most recent book examines the limits of presidential power.

“To have part of that history literally in the classroom was an amazing experience,” he added. “John Dean reminded us that he was barely ten years past his own undergraduate days when he was faced with extraordinarily hard choices in public service. To have him with us quietly reflecting back fifty years to assess those choices, bad and good, gave the students a compelling case study on the ethics of power. And those choices continue well past the event—as Tim Naftali showed us, the legacy of Watergate lives on in the very ways we commemorate and memorialize it. It was a really meaningful couple of days.”

Thanking an alum: Playing a key part in putting the event together, said Rudalevige, was Tom Putnam ’84, former director of the JFK Library and Museum in Boston.