Women's Contributions to Solving the Climate Crisis

By Rebecca Goldfine

The event, Women in Climate: Community, is the first in a series The Nature Conservancy in Maine (TNC) is organizing with partner organizations to spotlight the critical ways in which women are contributing to climate change mitigation and adaptation.

When women are involved in climate-related efforts, research has shown that their solutions tend to be more effective, long-lasting, and equitable. Additionally, as TNC director Kate Dempsey ’88 said at the event, women and children are disproportionately impacted by the worst of climate change—drought, floods, displacement, and other hardships.

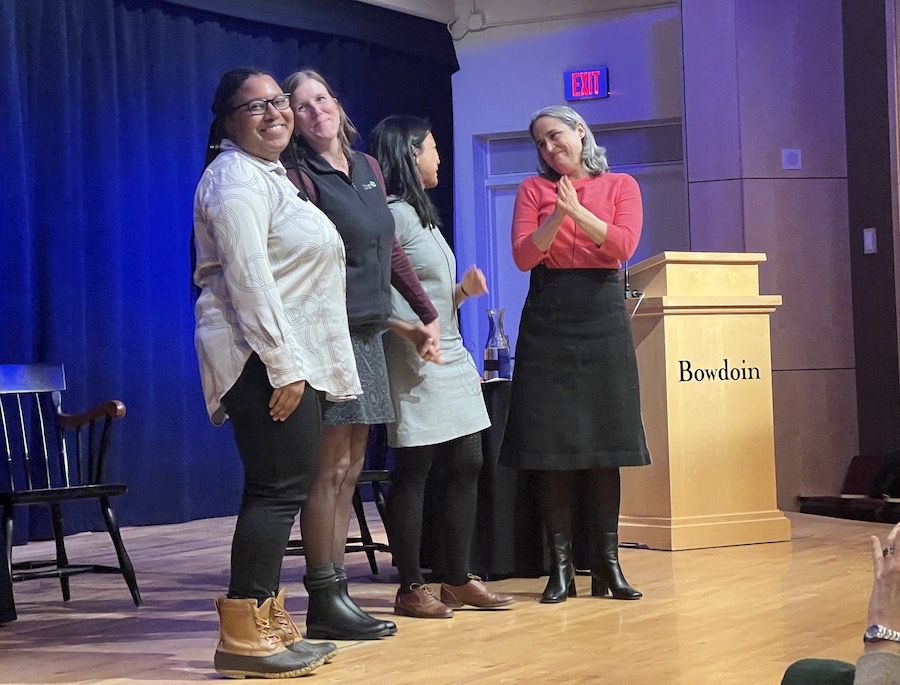

Despite the seriousness of the subject, the speakers wove stories of hope, warmth, and humor into their hour-long conversation in Kresge Auditorium. The evening began with laughter and hugs and ended the same way.

Dempsey, who moderated the panel, concluded the evening by repeating some notable phrases she had picked up on and wanted to emphasize: "We are all we got," she said. "Women love plans. Reframe the conversation. Who gets to decide? Something was missing. We've been doing this work for a long time." And finally, "Where is the outrage?"

These sentiments emerged from a discussion that touched on many ideas, including the importance of environmental contributions from Black, Indigenous, and rural communities, the role of diversity and equity in climate work, and advice for students just starting out in the world of work.

Communities at the forefront

Williams echoed Dempsey's observation about the vulnerability of women to extreme weather events. But she took it a step further to note that among women generally, Black and Indigneous women—as well as communities of color—are most in peril.

But these people are far from victims. Instead, she said, they're often driving the movement for change. "Where the opportunity comes from with these frontline communities impacted by climate change is that they're often at the forefront of thinking about climate resiliency and action in holistic ways," she said.

She included rural people in her argument as well. "Rural communities are often cast aside as the reason for our conservation or environmental troubles," she said. "But, in reality, they're some of our most radical and fantastic thinkers of how we are to live with the natural world."

As an example of communities rising to the occasion during disasters, she recounted a story about getting caught in Jackson, Mississippi, during a fierce snowstorm in 2021. Jackson is one of the poorest cities in the country, and Black communities there have a history of "state abandonment and neglect," Williams said.

For eight weeks, people in Jackson already living on the edge of poverty went without electricity, heat, or water. A bridge linking a neighborhood to a shopping center in the suburbs had become impassable, cutting people off from grocery stores. Wiliams said women in one Black community quickly mobilized, organizing food, water, and blanket drop-offs. "Women are familiar with the state not offering aid," Williams said, "and realizing we're all we got."

"Climate crisis is a poverty crisis, it's a water crisis, it's a food crisis. If we're not in a position to address all of those, then there is no climate action or resilience that will be successful in this country or around the world." Teona Williams ’12

As an environmental planner in Boston, Du focuses much of her time on climate action and emergency preparedness. She recalled a period when she and other city officials were engaged in discussions about vulnerability assessments, including deciding which infrastructure and facilities were the most important to protect. But "it became clear that something was missing," she said.

At the time, Du raised the questions "Who is deciding what is critical infrastructure? Who gets to be the decision-maker about what is necessary during an emergency? Whose voices are we missing?"

A lesson emerged from this work: the city needed to "make the table bigger and invite more vulnerable populations and those in communities of color to it so they can be part of our decision-making," Du said.

Pinard told a story about TNC's work with a community in northern Maine, which is an important region for forest conservation and outdoor recreation. It's also suffering from a long and painful social and economic decline due to the outsourcing of the forest products industry.

TNC, which owns a large tract of forest in that part of the state, decided not to be a remote landowner. Instead, it got involved in conversations with local stakeholders about how to envision and create a better future for the area. It also helped raise funds to support these efforts. In time, this collaboration led to the creation of the Katahdin Gazetteer: A Roadmap to the Future, a community-created guidebook for the region.

"We learned what the community needed from us," Pinard said. "The Nature Conservancy is at its best when it's connecting with and elevating communities."

The panelists frequently emphasized the need for institutions or those with power to listen to local people and to understand their concerns. Conservation organizations in particular have a history of being led by white directors and of coming into communities with a narrow focus, such as protecting habitat or biodiversity.

"It would be much different if institutions came in as comrades, amplifying local people's work, channeling resources to their work, and fighting alongside them," Williams said. "Rather than coming in and saying, 'We want this land to be a conservation easement, and we'll work with you long as you want this to be a conservation easement too!'"

She mentioned the deadly protests in Atlanta, Georgia, against the development of a 350-acre forest for a police training complex. On January 18, police shot and killed an activist. "Where is the outrage from mainstream conservation organizations?" Williams asked. Those organizations could have been supporting the protest and protecting activists, especially the ones "putting their bodies on the line and who are more susceptible to police violence."

Dempsey asked the panelists what advice they would give to students. Pinard urged young people to recognize how important their constituency is. "Your voice matters. You matter. Youth are leading the charge when it comes to climate action," she said.

Williams told them to "enjoy the connections that come with being at a school like Bowdoin," where mentors and friends can support you and remain connected to you for many years.

Du answered with a suggestion for the male members of the audience. "For the men in the room, make space for the women, the female leaders in your lives, your college, and your work. Make space and listen."

In answer to a question from an audience member about how to achieve environmental justice or environmental protection in the face of antagonistic forces such as white supremacy and capitalism, Williams responded by paraphrasing a teaching from one of her favorite activists, Fannie Lou Hamer.

"If we shift our perspective to helping the most marginalized, then we're automatically helping everyone, and we are actually protecting the environment, and we are actually protecting the climate and moving against these racial and capitalist productions," she said.

Dempsey drove home the point of how important collaboration, connection, and conversation are in the effort to protect the environment and battle climate change. When a woman in the audience asked what role love plays in the speakers' work, Dempsey threw her head back and laughed. "That is my favorite question!" she said.

She continued, "Relationships and trust have, for me, as a state director of an organization that has tremendous power, the highest values," she said. "That means you can't come and go." For insance, because TNC has a long-term relationship with fishermen in Port Clyde, she can call members in that community to sit down and work out differences of opinion on issues like offshore wind. "For me, relationships are central. Love is what it is all about."