The Decline of a Civilization

By Charlie O'Brien '23Peter Elmore, professor of Latin American literature and culture at the University of Colorado–Boulder, visited Bowdoin earlier this month to discuss his most recent book, Los juicios finales: cultura peruana moderna y mentalidades andinas*(Lima, 2022), and to talk with students in Associate Professor of Romance Languages and Literatures Carolyn Wolfenzon’s class, Modern Worldview of the Andes, which is crosslisted in both Latin American and Urban Studies.

Elmore began the public talk, titled “Afterlives of the Inca: The Long History of Apu Inka Atawallpaman,” with an analysis of an 1867 painting by Peruvian artist Luis Montero depicting the funeral of Atahualpa, the last king of the Inca Empire. Montero, then living in Florence, used the corpse of an Andean man as a model for the dead Atahualpa in his painting, which serves to underscore widespread historical fascination with the decline of the Inca Empire during Spanish conquest. We know from chronicles such as Inca Garcilaso de la Vega’s Royal Commentaries that Atahualpa was captured in Cajamarca, Peru, and that he converted to Catholicism to avoid being burned alive. (He was strangled instead.)

Elmore emphasized how, in Indigenous cultures that had revolved around oral tradition, the written word suddenly asserted its power during first contact between the Conquistadors and Atahualpa. Felipe Huamán Poma de Ayala and Juan de Santa Cruz Pachacuti Yamqui, who were Indigenous men who converted into fervent Catholics, were other chroniclers who wrote about early colonial Peru.

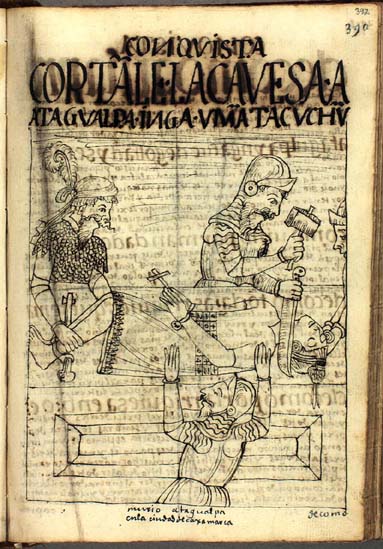

Elmore was intrigued by many of the drawings from Huamán Poma’s chronicles, which expressed not only the Andean writer’s fascination for the written word but also for printed books, which he tried to imitate with his handwriting and drawings.

Spanish conquest of Peru did not occur overnight, Elmore argued. Rather, the process of colonization lasted several decades, during which conquistadors engaged in civil wars and in which Indigenous communities—among them, the neo-Inca state of Vilcabamba—carried out significant anti-Spanish rebellions. In one drawing by Huamán Poma, Atahualpa is lying prostrate, holding a cross as he is beheaded by Spanish soldiers. According to Elmore, this is an important drawing not because of its historical accuracy—Atahualpa was strangled—but because it symbolizes how society and culture as Incas knew them were dismembered over the course of colonization.

The death of Atahualpa is often conflated with the death of Tupac Amaru, the last Inca king of Vilcabamba, into a single execution of great symbolic resonance. It is also compared to the execution of Tupac Amaru II in Cuzco in 1781, Elmore asserted. Tupac Amaru II, a rich regional leader and merchant, claimed to be a direct descendant of Tupac Amaru (who was hanged over a century earlier), and over time was regarded by many as the Inkarrí—meaning "Inca King" (the word is a compound of “Inca” and “Rey”, although “Inca” also means king). He was killed by the Spanish military (dismembered in public), but died a hero among the people who followed him in rebellion against Spanish rule.

Accordingly, themes of ominous ends and collective grief are evident in the poem Elmore analyzed, “Apu Inka Atawallpaman,” written anonymously in early colonial Peru memorializing Atahualpa. Elmore credited José María Arguedas, a renowned Peruvian writer and anthropologist, with the most faithful translation of the poem into Spanish. The first stanza references a black rainbow, which is significant considering that the emblem of the Inca was the rainbow. However, the poem ends in a manner that is more focused on the future than the past. The last stanza pleads with the Inkarrí to open his eyes and extend his generous hands, which, Elmore argued, is comparable to the coming of a messianic figure during the resurrection, at the end of times—both an apocalyptic sign and a sign of new beginning. The poem also imitates the meter of medieval Spanish poetry, although it is written in Quechua (an Andean language) revealing evidence of the cultural mixing that still characterizes the region today.

The central idea of Elmore’s book is that the myth of Inkarrí, known to anthropologists since the mid-1950s, was already dying by then in the Andean region but exerted an endurable fascination on Peruvian intellectuals, who ended up basing that myth—and others, like the Pachacuti myth—on their understanding of what they called the “Andean world.” This “Andean world,” Elmore argued, was construed by Peruvian intellectuals rather than actually discovered by them, but the notions of Inkarrí and Pachacuti became so influential that they went on to live in the ideas of those who described it, like Arguedas himself.

What happened in colonial times resonates with contemporary life, Elmore said in closing. "Narratives, symbols, and ideas can lead to action and shape reality. That's one of the main reasons why we study the Humanities."

*The final judgments. Modern Peruvian culture and Andean mentalities.