Exploring America’s Persistent Use of Torture Over the Last Century

By Tom PorterGiven that torture is both incompatible with liberal values and often an ineffective way of extracting information, why would a liberal democracy such as the United States persist in using such interrogation methods?

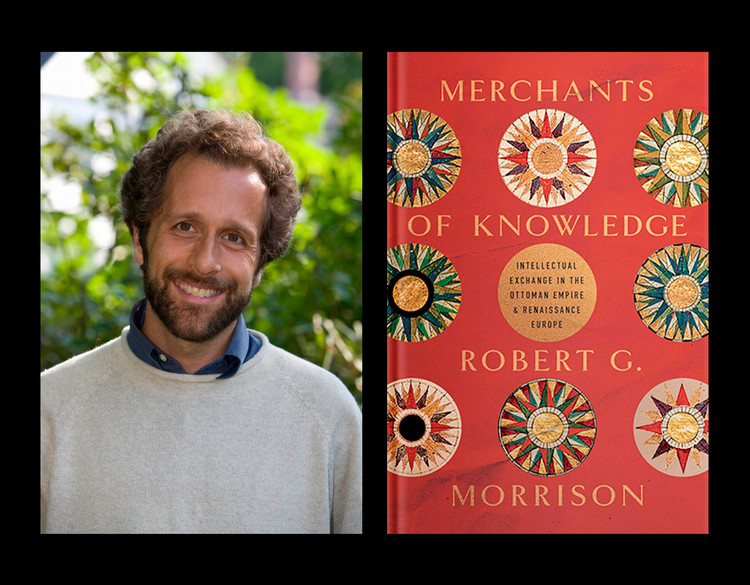

This is the question Visiting Assistant Professor of Government William d'Ambruoso addresses in his latest book, American Torture from the Philippines to Iraq: A Recurring Nightmare (Oxford University Press, 2021).

D’Ambruoso examines three conflicts the US has been involved with over the last century or so: the Philippine-American War (1899-1902), the Vietnam War, and the post-9/11 war on terror. These were all wars with a high degree of insurgency and counterinsurgency activity, says d'Ambruoso, and it is in these types of conflicts where torture is more likely to occur on both sides.

“The US record on torture and prisoner treatment during conventional wars like World War II, for example, was somewhat better,” he explains, “whereas in unconventional counterinsurgency and counterterror campaigns, we see Americans denying prisoners full POW status, we see more indefinite detentions, and more widespread use of torture.”

The frustration of fighting an opponent who is not in uniform and unlikely to follow norms like the protections in the Geneva Convention caused many US operatives to resort to torture, even though some of them knew it was illegal (or close to it), says d'Ambruoso. “This was born out of a belief among some policymakers and soldiers that in the nasty world of international politics, it’s sometimes necessary to break the rules to get results. ‘The other side isn’t fighting fair so neither will we,’ is the mindset.” D’Ambruoso describes this as the “Cheaters Win” approach.

In the case of the US-Philippine War, the Filipinos, fighting for their independence against the Americans, moved toward guerrilla tactics after conventional warfighting proved unsuccessful.

In Vietnam, the US involved itself in a brutal civil war underpinned by a paranoid Cold War mindset, notes d’Ambruoso. This conflict also saw the CIA entering the fray, with its emphasis on the psychological torture of suspected Vietcong and North Vietnamese Army captives.

The frustration of fighting an opponent who is not in uniform and unlikely to follow norms like the protections in the Geneva Convention caused many US operatives to resort to torture.

The twenty-first century war on terror in Iraq, Afghanistan, and other places, saw elements of the military and the CIA, as well as private contractors, employing so-called “enhanced interrogation techniques” with White House approval, despite increasing congressional scrutiny, as well as scrutiny from the media and monitoring groups like Amnesty International.

A worrying pattern d’Ambruoso identifies in all these cases is the use of “stealth” torture or “torture-lite” techniques, where no physical marks are left on the detainee and no lasting physical damage inflicted (although this was not always the case, he observes.) “Because the definition of torture is blurry, this enables certain actors to justify to others and even themselves the use of milder methods.” This could mean, for example, the use of techniques like sleep deprivation or waterboarding rather than physical beatings.

D'Ambruoso also describes an attitude especially prevalent during the war on terror, in which American perpetrators of torture had half an eye on how they would justify their actions should they be held to account later. “What I found is that while they’re hiding what they’re doing, these perpetrators are also making efforts to sell their activities as legitimate once the hiding game is up. It’s like they knew they would be caught so they're getting their story ready.”

Given the intense criticism that US intelligence agencies and elements of the government have attracted in recent years, is d’Ambruoso hopeful that the days of America torturing its enemies are over? “It’s hard to know,” he says. “Certainly, the CIA and military bureaucracies don't want to go through what has happened since the war on terror again. One former CIA director even said that if President Trump wanted to waterboard detainees then he'd have to bring his own bucket.”

There is no such reluctance among certain politicians, however, says d’Ambruoso, again referencing Trump as an example: “He praised the Philippine’s leader Rodrigo Duterte’s extrajudicial killing spree against alleged drug traffickers as an ‘unbelievable job.’” The former president also admired the lack of institutional constraints in Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s Turkey, he notes. “Torture, once universally condemned, has become a partisan issue in the United States.”

In conclusion, d'Ambruoso says his biggest concern is the possibility of a certain type of torture coming to be regarded by many as an acceptable activity, in the same way he sees other democratic norms being eroded in the US. It’s all part of what he calls the “normalization of horrible things.”

This semester d’Ambruoso is teaching United States Foreign Policy (GOV 2670) and International Security (GOV 2680)