Growing Up NESCAC

By Dan Covell ’86 for Bowdoin MagazineFrom coach’s son to undersized lineman to professor of sport management, author Dan Covell ’86 has been steeped in the New England Small College Athletic Conference.

As he publishes his new book, The New England Small College Athletic Conference: A History, on the heels of the conference’s fiftieth anniversary, Dan reflects on his education in “the sweatiest of the liberal arts.”

When someone learns that I've just completed the manuscript for my book on the history of the New England Small College Athletic Conference (NESCAC), I’m often asked, “How long were you working on it?” “Since August of 1969,” I reply, only slightly in jest.

I don’t remember the precise date, but the image of the moment when I began is clear. After a decade of success as a high school baseball and football coach at Orono [Maine] High School, my dad, Wally Covell, moved the family to Waterville to take a position as assistant football and baseball coach at Colby. (Yes, back then NESCAC coaches coached multiple sports, as well as taught physical education classes. Many Bowdoin alumni will recall that Phil Soule probably coached every sport offered at one time or another.)

In 1969, at age six, I arrived in the middle of Colby preseason football double sessions at the front of Colby’s then-brand-new state-of-the-art field house. Sitting on one of the benches attached to the Brutalist concrete slab near the front entrance, gathering himself after a sweaty day in the trenches, was six-feet-six, 235-pound offensive tackle Luthene “Luke” Kimball, from Cape Cod. Luke was big by late ’60s standards, and gigantic to me. I’m told I’d been going to my dad’s practices and games since birth, but I have no clear recollections of any such moments until this one, when Luke said “Hi.” I’m not sure what I said in return, probably nothing, as I was in awe. By all accounts, Luke, who died too young from pancreatic cancer in 2004, was a great teammate and a better guy, and uniquely gifted to serve as an effective bouncer at his fraternity parties. I had encountered my first NESCAC giant.

That moment began my more than half century (and counting) association with NESCAC athletics. Prior to my matriculation at Bowdoin in the fall of 1982, I had spent a great many hours at practices and games, traveling across New England, to New York, and to Florida—my first flight was with my dad and the Colby baseball team on its southern spring break trip in 1973—and sitting in on coaches’ meetings and recruiting visits. I kept the scorebook for Colby baseball when my dad became head coach—the coldest I’ve ever been in my life was during a doubleheader at Trinity on a frosty, blustery, early-April day in the mid-1970s, my own personal “Ice Bowl,” when I couldn’t move my frozen fingers to finish scoring—and called the game stories in to the local newspapers (occasionally having to make up opposing players’ first names if they weren’t on the lineup card).

So many of my father’s players spent time at our house laughing, eating, and telling stories. Wins were celebrated, losses were mourned. Assistant coaches lived in our finished basement, while another lived across the street. In short, there was no distinction between the goings-on associated with NESCAC athletics and our family—to wit, my two sisters are both married to former NESCAC athletes.

From this context, I was able to view players, coaches, and administrators not only as role models, but also as subjects of interest as they carried out the functions associated with their jobs—and these were jobs, not just educatory avocations. These stakeholders wanted to win, and NESCAC dicta such as the team sport ban on NCAA postseason play, as discussed in the book, was a seminal issue in the evolution of the conference. The ban was widely if not universally reviled as unfair and restrictive, as individual sport athletes like swimmers and cross-country runners were able to compete in NCAA championships, but team sports were barred.

My time at Bowdoin allowed me the chance to experience NESCAC from the participants’ perspective. While I played football at Bowdoin, I didn’t come to Bowdoin to play football. I was hardly recruited after a prep school postgrad year, and I’d be shocked to learn that my name was on any coach’s list provided to admissions. Football at Bowdoin was fun and fairly serious— the team won the Colby, Bates, Bowdoin Championship (CBB) in ’84 and ’85—but it was by no means the defining aspect of my undergraduate experience. Preseason lasted three days, as opposed to the two weeks of double sessions I had in high school. If you wanted to work out in the off-season, that was your call. I do remember practicing long-snapping on Whitter Field the summer I worked on the campus grounds crew, with my then-girlfriend fielding the snaps. That must have been quite an image to passersby on Pine Street.

I was a studio art major, but I spent much of my time and energy associated with WBOR, serving as music director for my last three years (interrupted by a wonderful term abroad in London the spring of my junior year), and my enduring friends from that time are invariably those with whom I worked at ’BOR. I failed second semester Greek my freshman year, as that’s what happens when you skip class for three straight weeks. Professor John Ambrose did me a great favor in giving me the grade I deserved.

I did letter in football junior and senior years, and unsurprisingly, won no academic awards. Bowdoin allowed me to fail and to succeed based on what I put into the experience. That was an important lesson and one that I impart to my current students every day. By the way, on the first day of each class I ask my students what position they think I played in college. Most probably think kicker, but they usually say “running back” or “safety.” They are genuinely surprised when I respond with “center,” as my current six-foot, 195-pound frame belies the fact that I played at only twenty-five pounds heavier, which was fairly average for linemen back then. All of this was, I think, a typical NESCAC experience.

My career in teaching began thanks in part to art professor Kevin Donahue, who allowed me to serve as an informal student teacher in his spring term introduction to painting class. I was looking at prep school teaching and coaching jobs (after all, education was the family business; my mom, Janet, was a lifelong early-childhood educator and helped launch one of the first-ever Head Start programs in Maine), but I didn’t have any formal teaching experience, so I asked Kevin if I could work with him to gain some.

After graduation, I secured a job teaching, coaching, and living in a dorm at a private school in Minnesota, and I headed west for four years. I became head football coach for one year—and went winless. (I don’t blame the players.) After I married Pam Safford in 1988 (in a Bowdoin Chapel service, with a reception in Cram Alumni House), we moved back to New England in 1990, and I became athletic director at a public high school in Vermont. In 1994, I entered grad school at the University of Massachusetts with the intent of becoming a college athletic director (AD) like my NESCAC mentors.

It was during my time in grad school when I opted to move toward the teaching side of higher ed. More specifically, it was during my internship in the athletic department at Harvard (where my supervisor was future Colby AD Marcella Zalot—NESCAC mentors, again) when, in addition to other responsibilities such as running special events and NCAA rules compliance, I was named the interim aquatics director, a position for which I was only nominally qualified. The main part of the aquatics job was being present in the office and at the pool to supervise the students who were lifeguards and taught swimming lessons. As any facility manager knows, many bad things can happen in pools, and these roles students were filling (and filling well) were serious endeavors geared toward avoiding those bad things. Connecting with these talented students reminded me of my interest in aiding other future sport managers, so I returned to UMass the next fall to begin work on a doctorate in sports management.

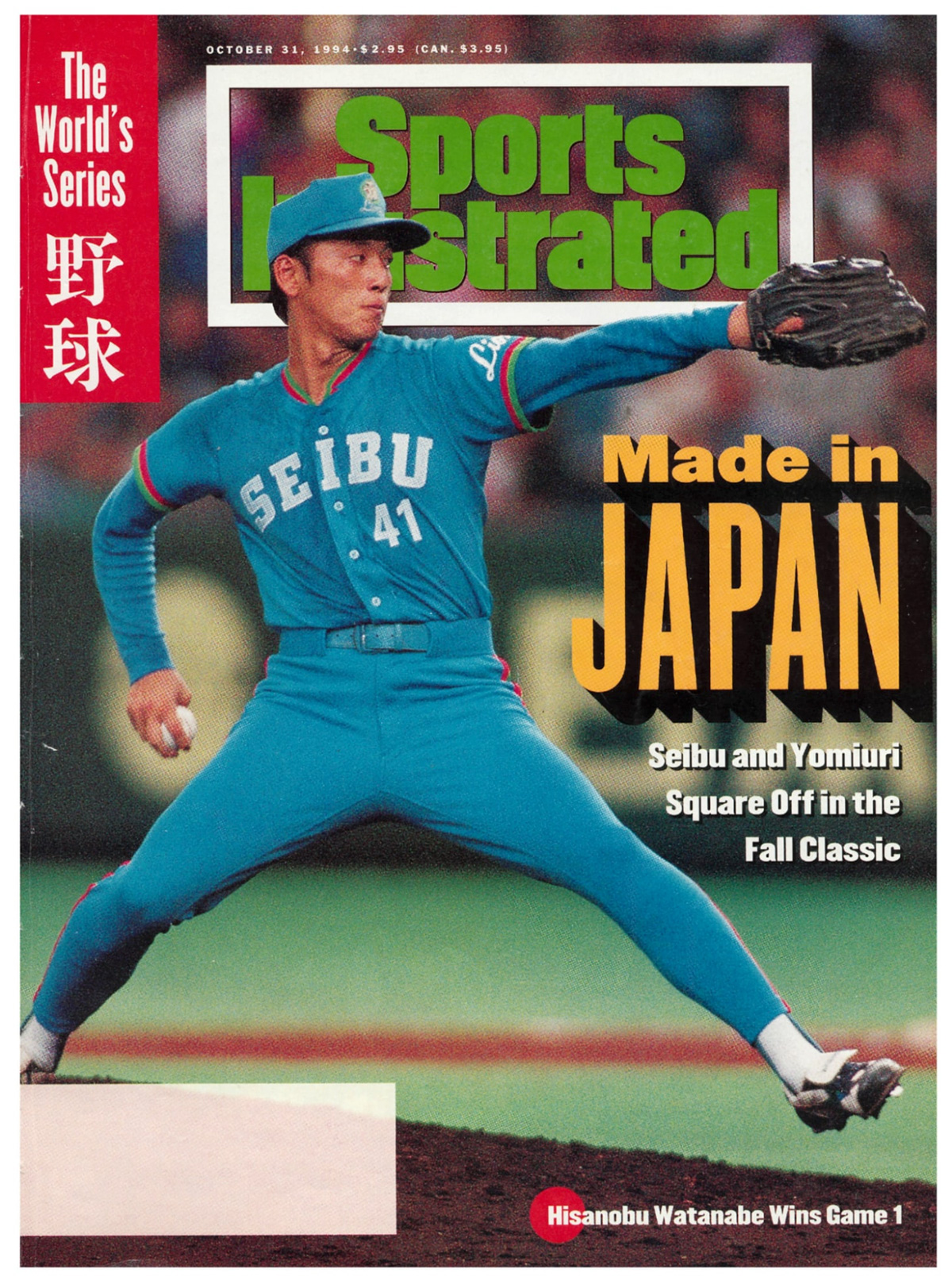

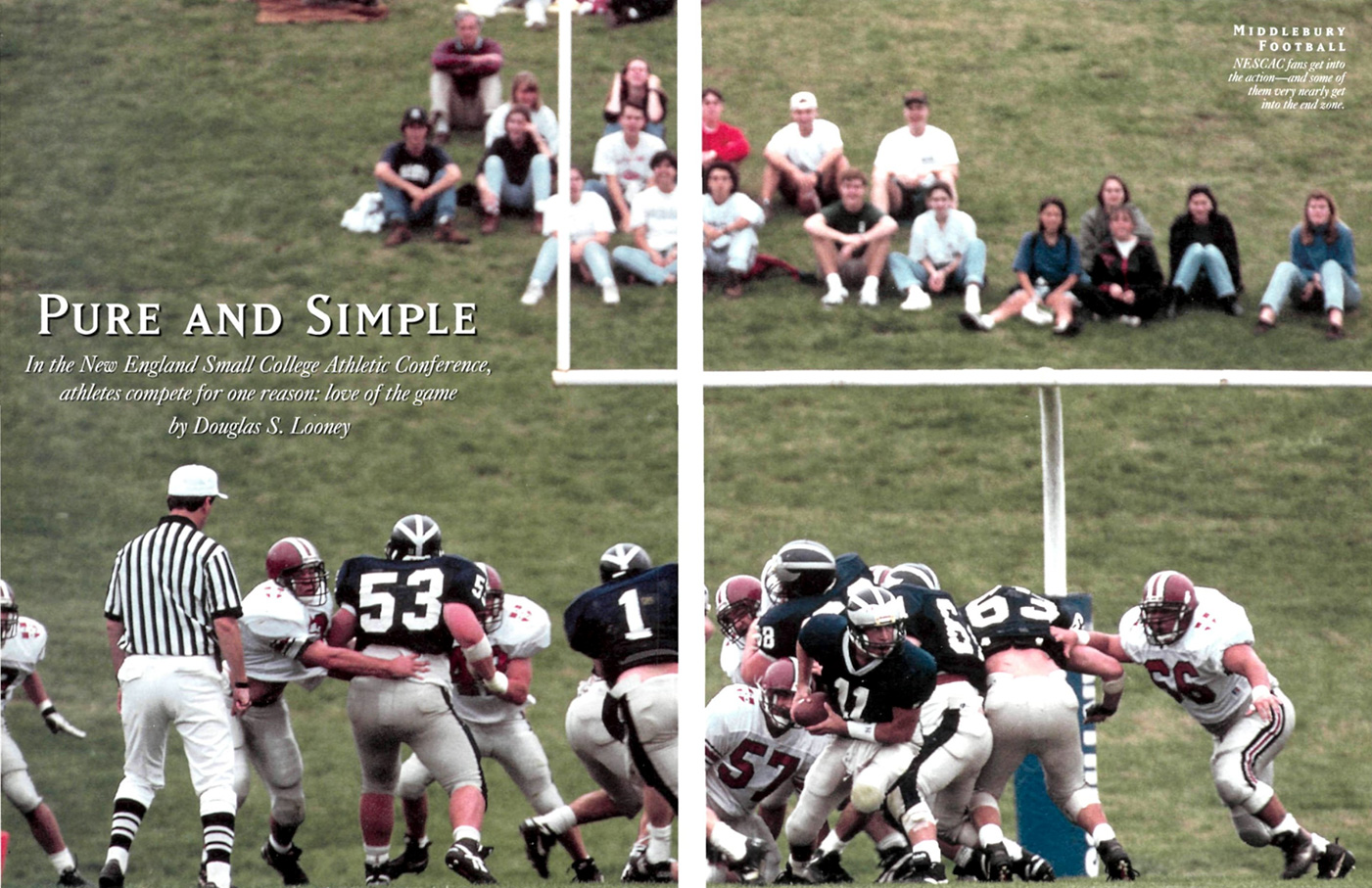

Two years prior to my return to UMass, Sports Illustrated had published an article titled “Pure and Simple,” by staff writer Douglas Looney. The magazine had just celebrated its fortieth anniversary, and while it had ceded some ground to the likes of burgeoning media giant ESPN, according to a later historian, SI was still the “authoritative surveyor of the American sporting scene to its many readers.” Given the magazine’s status and its dedication to covering sporting events and personalities of both national and international import, the overwhelmingly positive article was a tremendous boon for the cultivation of the ideal image of NESCAC. The piece—complete with over a dozen full-color photos of NESCAC fall sports action—served as a landmark homage and touchstone for NESCAC stakeholders around the world.

Reading Looney’s article, the tone and content of which couldn’t have been more laudatory if drafted by a think-tank of NESCAC publicists, one might take the author for an intercollegiate athletics naif. Nothing could be further from the truth, as Looney, who had been writing for SI since the early 1980s, was an experienced investigative reporter. Perhaps Looney was smitten with the imagery encountered in researching the NESCAC story, given what he’d seen and experienced covering the big time. After all, in the wake of a critical piece he’d written on University of Colorado head football coach Chuck Fairbanks, Looney commented that he got a lot of negative letters, but that “most of them are in crayon because they don’t give these people sharp things.”

Looney rhapsodized about the idealized campus settings in which NESCAC athletics reside. “The Amherst College campus is too collegiate,” he writes, “the ambience too New England, the whole picture too Norman Rockwell. The grass is cut, and the flower beds are weeded. There is no trash. The sky is true blue.” He cites the experiences of a Middlebury football player who “spent many a fall afternoon looking out over Vermont’s Green Mountains, resplendent in the fall red produced by sugar maples, and pondering the Middlebury experience.”

While Looney concedes that “of course, NESCAC schools aren’t very good in most sports,” he identifies this perceived shortcoming as an attribute. “But they are not very good only if you measure the Colby football team, for example, against Miami’s; the Bates basketball team against Arkansas’s. And such comparisons miss the point... Insofar as sports are concerned, things are perfect, or pretty close to it.”

That vein allowed Amherst (and former Trinity) president Tom Gerety to contextualize NESCAC in lofty philosophical terms: “Sports fulfill the natural drive to test oneself against others. It’s our greatest ritual, short of war. I don’t have much trouble justifying them, but that’s only in this kind of setting. It seems everywhere else, sports are a distorting force.” Gerety then sought to bring athletics into the liberal arts rubric when he commented: “Be it poetry, acting, philosophy or athletics, any youngster has more to give than what is called for in a traditional class ... [Athletics is] the sweatiest of the liberal arts.”

Looney’s piece signaled to me that NESCAC now felt like something different from what I knew. The challenge NESCAC managers faced and continue to face is how to keep things pure while they have become decidedly less simple. It now seemed like a national intercollegiate athletics brand, and I wanted to learn what that meant. For my dissertation, I sought to investigate the meaning of athletics to three important institutional stakeholder groups: faculty, student-athletes, and presidents. I sent a then-high-tech email message to Bowdoin AD Sid Watson, who was chair of the NESCAC ADs committee, to ask if he had any interest in my study and if he would like to help in the collection of data. I had never met Sid during my time at Bowdoin, but I figured he knew my dad from his Colby years and that he might be willing to help out an alum. Sid agreed, and I was able to gather extensive survey informa- tion that became the core of my dissertation research. For that I am forever grateful, and in the dedication of the book, I make specific mention of this NESCAC giant’s assistance.

Dissertation completed and doctorate in hand, I started teaching in the Department of Sport Management in the School of Business at Western New England College (now University) in Springfield, Massachusetts. Several years ago, when consultants instructed the school to pursue university status because “most people think colleges are not as academically rigorous as universities,” I responded, with an arched brow: “Really? What about Bowdoin? What about Amherst? What about Williams?”

Along with helping students gain entry to their careers in sport, my research revolved around the issues I had encountered as a high school AD and as a ward of the NESCAC. When I received a sabbatical in 2010, I decided I wanted to dive into the archives in Hawthorne-Longfellow Library and see what I could find concerning the history of Bowdoin athletics and its place in the NESCAC. Pam and I had purchased a house on Coombs Road in Brunswick (the first house we viewed turned out to be the Watson family house on Longfellow Avenue), and I could decamp there for the fall and into the reading room in Special Collections.

My time at UMass had shown me the dedication and creative problem solving of reference librarians and archivists. They were the angels on the shoulders of we grad students, and the same was true at H-L, especially Caroline Moseley and Kathy Peterson. I was not a historian by trade or training, so sifting through the letters, memos, reports, and studies of Bowdoin luminaries such as Mal Morrell, Roger Howell, and Casey Sills with their guidance was both illuminating and instructive. These documents were the portal through which I first learned and developed many of the lines of inquiry outlined throughout the book. By the end of the first week of the sabbatical, I’d already spent more time in H-L than I had during my entire undergraduate tenure.

After penning a few academic journal articles on the topic of Bowdoin and NESCAC, I felt it was time to compose a full-length book study. One of the salient issues I found was when Union College was kicked out (or left, depending with whom one speaks) over recruiting violations by its head men’s ice hockey coach. On this topic and several others, I turned to another giant, the world’s foremost hockey historian, Steve Hardy ’70, former ice hockey cocaptain with his twin brother, Erl ’70. Steve, who also coached at Amherst and worked for the ECAC (Eastern Collegiate Athletic Conference), brings the book to life with first-person observations about how Union built its hockey program and would eventually run afoul of conference rules.

Other NESCAC figures added their invaluable insights, such as former Amherst AD and men’s soccer coach Peter Gooding, former Williams men’s basketball coach and AD Harry Sheehy, former Middlebury president Ron Liebowitz, former Hamilton president Eugene Tobin, and former Williams president John Chandler. But Steve Hardy was the keystone, and he wrote the foreword for the book, in which he recounts his son Ben’s time as a men’s soccer player at Middlebury.

It is often said that if we see further, it is because we stand on the shoulders of giants. Writing this book made this abundantly clear to me. Because of giants like Kimball, Watson, Hardy, and so many others, I am forever grateful that I was able to grow up NESCAC.

This story first appeared in the Spring/Summer ’22 issue of Bowdoin Magazine. Manage your subscription and see other stories from the magazine on the Bowdoin Magazine website.