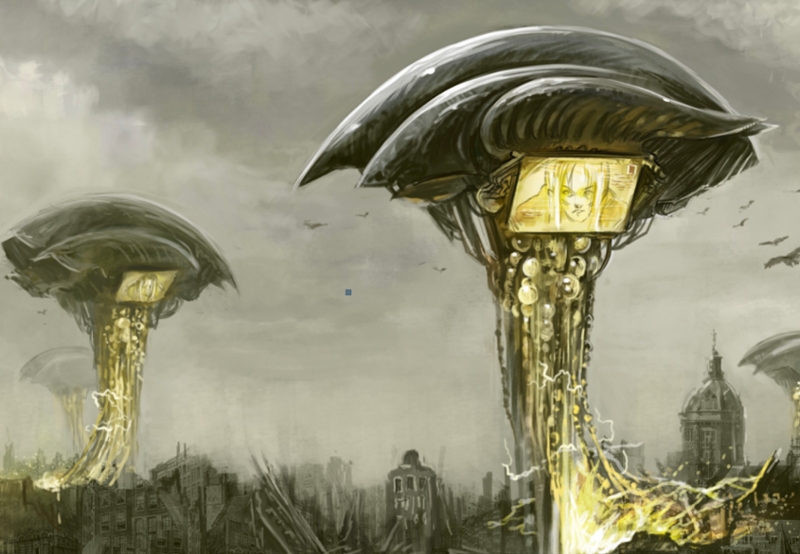

“Is Anybody Out There?” (What if the Answer is Yes?)

By Tom PorterThe initiative is the work of Berkeley SETI Research Center—a California-based nonprofit research group that employs radio telescopes and listening devices to search for signs of life beyond our planet (SETI stands for “search for extraterrestrial intelligence”).

“These scientists are generally very keen to find out if there is any extraterrestrial life, but they often haven't really focused beyond that step. They asked us to consider ‘okay, if this does happen, what happens next? How do we behave? What are we missing?’ And there are several ethical concerns that we presented.” Lempert was a member of SETI’s Indigenous studies working group,* which last year issued a statement exploring the concerns they have and some of the recommendations that scientists could take away from fields related to Indigenous studies, including anthropology.

The focus of much of Lempert’s day-to-day research is on the challenges facing Aboriginal Australian communities, particularly how they are represented in film and media, but he has also long-nurtured an academic interest in the anthropology of outer space and in science fiction—how writers have portrayed the future, particularly the relationship between the Earth and other planets.

A Lesson from Colonial History

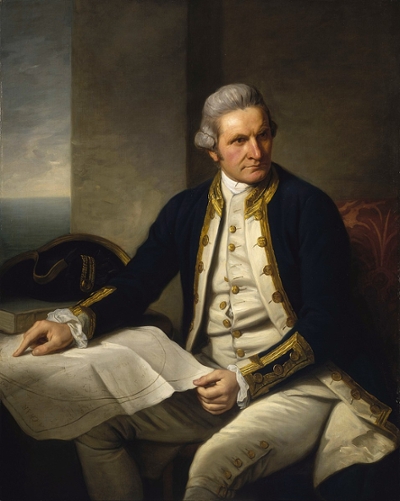

In an article he wrote in 2021 for the American Indian Culture and Research Journal, Lempert took a historical perspective to draw interesting parallels between the eighteenth-century British explorer Captain James Cook and the issues facing scientists today as they look for extraterrestrial life.

“In 1768, when Cook and his crew left England on HMS Endeavour, it was with altruistic intent and supposedly for the benefit of mankind,” writes Lempert. “This voyage was ostensibly a scientific expedition to measure the transit of Venus in Tahiti, which was part of a global project to calculate the distance between the Earth and the Sun.” During the course of his travels, however, Cook “discovered” the land masses that became Australia and New Zealand, or Australasia.

Inevitably, explained Lempert, and despite the best intentions of Cook and his backers at the Royal Society in London, the Endeavour’s achievements led to colonization and centuries of “violent dispossession” suffered by Australia’s Indigenous communities. What took place was a kind of “mission creep,” explained Lempert, where the pull of wealth-creating colonial expansion proved impossible to resist.

In this instance, explained Lempert, scientific progress and colonial expansion proved inseparable, and it’s his concern that a similar dynamic could unfold as scientists reach out further and further into space, perhaps one day finding evidence of extraterrestrial life. The often-laudable goals of scientific discovery, he added, are much more palatable than that of financial gain and resource exploitation, and that’s as true today as it was 250 years ago.

“These scientists are generally very keen to find out if there is any extraterrestrial life, but they often haven't really focused beyond that step. They asked us to consider ‘okay, if this does happen, what happens next? How do we behave? What are we missing?’ And there are several ethical concerns that we presented.”

“If you had space project leaders talking about missions to grab alien technology and mine asteroids, the public would really not appreciate it and there would be a backlash. However, if the aim is presented as purely for the advancement of science, the mission has more public legitimacy.” Lempert said he doesn’t doubt the good intentions of the scientists at SETI, but he fears that if they are successful in picking up signs of extraterrestrial life, they would be unable to control what happens next and negative consequences could ensue, with humans colonizing new planets and exploiting their resources.

Divvying up Outer Space?

“The British claimed Australia by arguing it was effectively unoccupied and therefore open to be conquered,” writes Lempert in his article. He is worried that the same kind of “colonial expansionist logic,” where unknown land is effectively up for grabs, may be used with regard to outer space. Since the space age began, there have been efforts to regulate this new frontier and establish international space law with treaties such as the Outer Space Treaty (1967) and the Moon Treaty (1979), essentially frontier agreements intended to regulate space activity for all nations.

However, as mankind’s exploration of space gets deeper, maybe even identifying extraterrestrial life, the concern of anthropologists like Lempert is that political and financial imperatives will come to the fore and space will be seen as a source of power and profit—in much the same way as Australasia was following Cook’s initial “discovery.”

Celestial Wayfinding: Building on a Polynesian Tradition

So, what should we do to avoid this? How can scholars of Indigenous studies help us learn from the past as we navigate the next several hundred years of space exploration? In their joint statement, Lempert and his colleagues warn scientists against imposing their Western values in the search for extraterrestrial intelligence and implore them to be careful in using terms like “intelligence,” “advanced,” and “civilization,” especially beyond Earth.

“… SETI researchers should explicitly consider their own cultural grounding and reflect on how the assumptions that there are ‘advanced civilizations’ that encounter less advanced peoples (and associated excitement and fear) are forged in the fires of settler colonial violence in the Americas and elsewhere. These well-known colonial encounters form much of the intellectual foundation for current ways of thinking about ‘civilizations,’ often leading to uncritical assumptions about progressive linearity in the development of life. With this in mind, we suggest developing research protocols and a statement clearly outlining the principles of care you are using to guide your attempts at contact.”

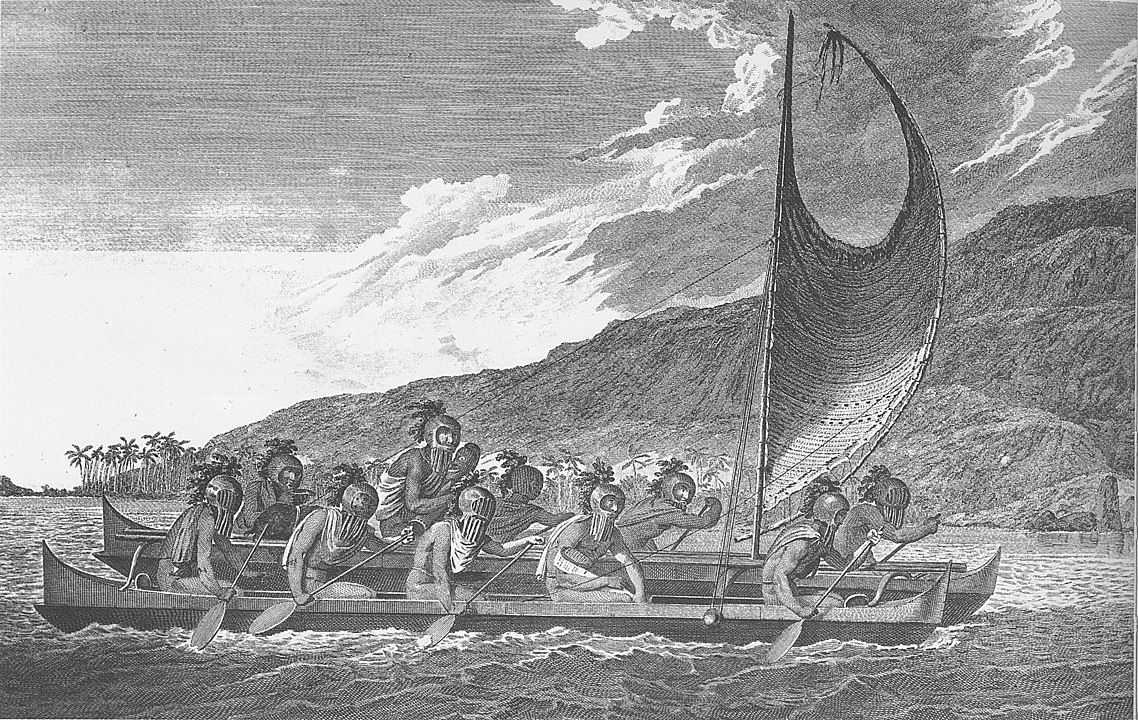

In his own paper, Lempert draws on the centuries-old tradition of Polynesian wayfinding, in which the islanders, traveling by canoe, performed extraordinary feats of celestial navigation to explore and discover new lands. “Broadly speaking, they did so in a noncolonial, nonexpansionist way, not regarding newly found territories as their own possessions to govern and exploit, but instead showing respect for their surroundings and protecting animal and plant systems from human harm.” Scientists working today at SETI, he said, would be well advised to ensure a similar attitude is adopted as new frontiers of space are explored.

Back to Earth

Lempert acknowledged that the chances of any major discovery of new life in the universe are very small and unlikely to happen in his lifetime. “Nevertheless, it is interesting and beneficial to consider such things, because by thinking beyond humans and the Earth, it helps us to newly think about humans and the Earth. It helps us see some of the things that we have done and are doing with new perspectives.”

Professor Willi Lempert returns from sabbatical leave in the fall 2022 semester, when he will be teaching Imagining Futures (ANTH 1016)

*Lempert’s collaborators in SETI’s Indigenous Studies Working Group are:

Sonya Atalay (University of Massachusetts, Amherst), David Delgado Shorter (University of California, Los Angeles), and Kim TallBear (University of Alberta).