How Pasta al Pomodoro Changed Everything

By By HISP 2306 StudentsMexican author Álvaro Enrigue gave a recent talk at Bowdoin about how the world changed after the Spanish Conquistadores defeated the Aztec empire 500 years ago.

Below are highlights from his presentation, as written by students from the Spanish Nonfiction Writing Workshop, a Hispanic Studies course taught by Associate Professor of Romance Languages and Literatures Carolyn Wolfenzon.

In addition to giving a talk, Enrigue visited Wolfenzon's workshop to talk about his chronicle El rapto de América (The Abduction of America), on April 6 and 7.

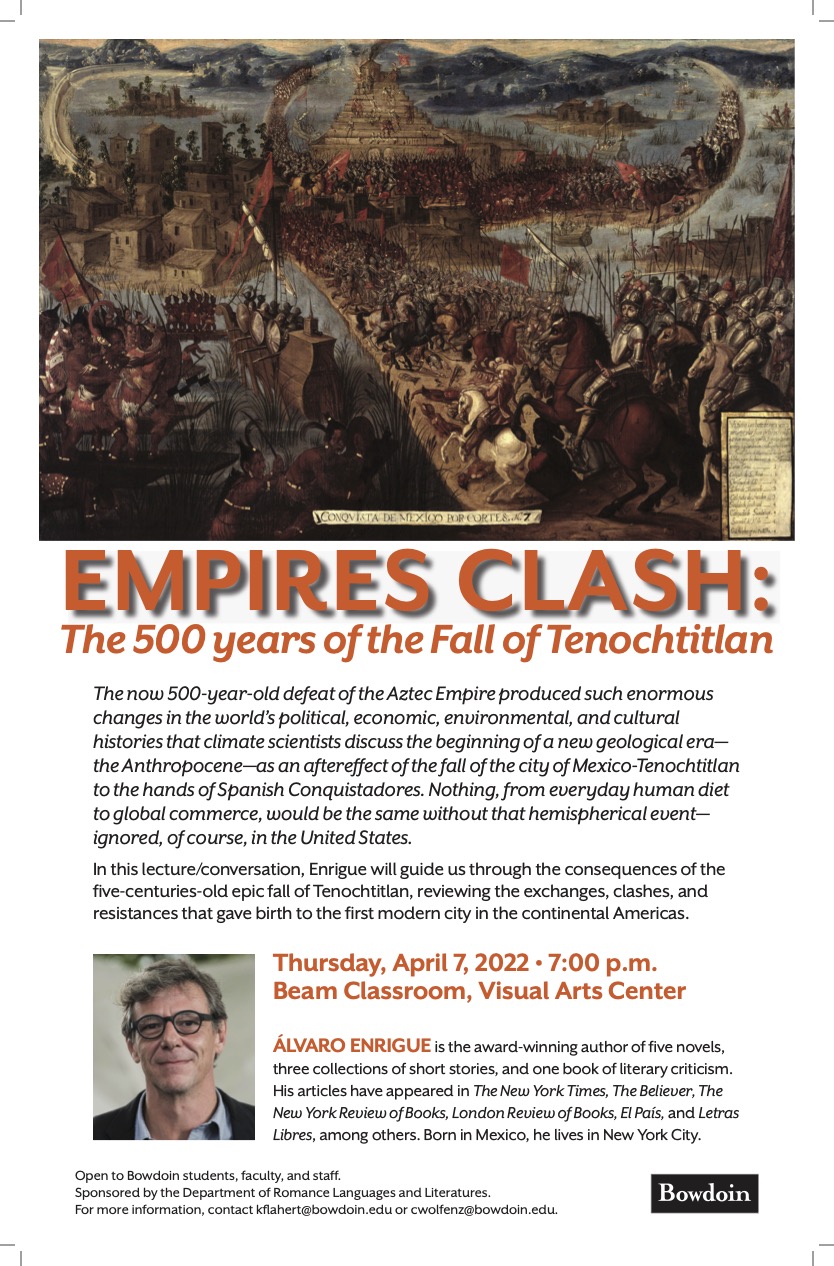

In his April 7 talk, "Empires Clash: 500 Years of the Fall of Tenochtitlan," Enrigue explored the ideas and controversies that have formed a foundation for his many books and articles, including Muerte subita (Sudden Death), Ahora me rindo y eso es todo (Now I Surrender and That’s All), and Hipotermia (Hypothermia).

He began his talk with a story about Pope Clement VII's craving for pasta al pomodoro—only possible after the Europeans invaded Central America. The tomatoes for this simple spaghetti dish (and other foods like corn and chili peppers) made their international debut after the Spanish conquered the Aztecs in the early 1500s.

With the toppling of the Aztec city of Tenochtitlan, the Spanish unleashed not just a new cuisine but a new global dynamic. The effects of the Spanish occupation were so dramatic that Enrigue argues it marked the beginning of the Anthropocene, the current era in which humans became the dominant influence on the climate and the environment.

The Spanish brutality that followed the conquest, and the introduction of devastating new diseases, caused the deaths of nine out of ten indigenous people in the first 100 years of occupation. The mass mortality caused carbon levels to fall, from the decrease of hearth fires and other man-made fires, enough for global temperatures to cool by 1610.

As this tragedy unfolded, Mexico City became one of the most metropolitan, globalized cities of the time. Enrigue even cited documented reports of visits by Samurai and the existence of an Irish pub.

Yet, one of the central messages he wanted the Bowdoin audience to hear was that the history of the Aztecs has always been told from the perspective of the winners, the Europeans, especially from Hernan Cortes, who is considered the figurehead of Tenochtitlan's defeat.

Cortes's chronicle is, however, mostly fictional, Enrigue said. (Cortes's version comes from his five Las Cartas de relación, or the “Letters of relations” he wrote to Emperor Charles, the king of Spain, about the destruction of the Tenochtitlan empire.)

The outcome from this is that a common narrative of the clashing civilizations is a glorified story portraying the Spanish as heroic and the Aztecs as weak, Enrigue argued.

Historians and writers today—including Enrigue—are correcting the record. They have discovered and analyzed primary accounts of the events that survived the destruction of the city and were not manipulated by the Spanish.

Contrary to the myth students are often told, the Aztecs were not a powerless people that succumbed to a more organized army with a more sophisticated war strategy. Rather, the advanced civilization collapsed due to the combination of war, famine, and disease. Although the spread of disease was likely unintentional in the beginning, Enrigue argued it was used strategically by the Spanish to inflict one of the largest genocides on the Native people they ruled.

The erasure of these people, their cultures, and broad collection of traditions—and the pitiful storytelling of Latin American history through the perspectives of the conquistadores—contribute today to continued misconceptions and misunderstandings of South and Central America, Enrigue argued.

The way that we tell history holds the utmost importance, he emphasized, reminding his audience that “history is always political.” Those who are the “winners” are the ones who write the global narrative that we teach our children and the generations to come.