Bowdoin Students Reflect on Joyce’s Dublin, 100 Years Later

By Jane Godiner ’23

The groundbreaking novel was published in 1922, shaking up the literary establishment and reshaping the trajectory of modern literature.

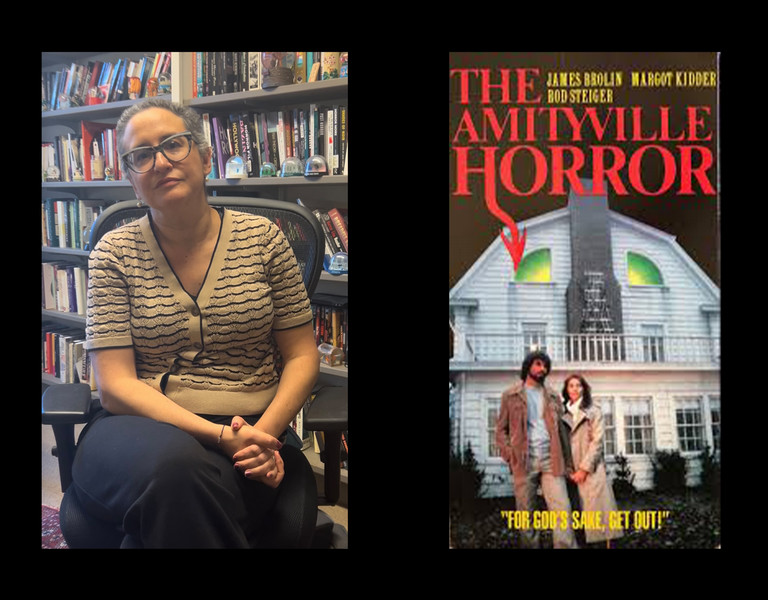

The students, who referred to themselves as the "Joyce Group," were inspired to make the journey after taking the advanced English seminar James Joyce Revolution, taught by Marilyn Reizbaum, Harrison King McCann Professor of English and director of gender, sexuality and women’s studies.

“I really, truly believe that Joyce revolutionized the novel form,” Reizbaum said in her opening remarks at the talk. “[The Joyce Group] embraced the novel with gusto, to the point that they lobbied to go to Ireland to do what Joyceans do: track the novel through the city of Dublin.”

The students received a Bowdoin grant to fund their itinerary. Though they were excited when they first set out, they also nursed some trepidation.

“The question confronted us: what are we getting into? How should we engage with these real-world traces of a fictional landscape? How much should we fetishize these locations and their role in the novel, and how much can we make our own meaning for them, above and beyond their Joycean significance?” Freeman said. “It was a question of double-exposure and of layering our own journey atop Bloom’s journey.”

Freeman also recalled their memorable encounter with P. J. Murphy, proprietor of Sweeney's bookstore, a canonical setting from the novel. According to local lore, Murphy has read Ulysses seventy-two times.

“We came into the little shop single file, and [Murphy] was sitting there in a white lab coat. He asked us, ‘Are you Joyceans?’ We said ‘Yes.’ He was quite pleased by this,” Freeman said. “The novel was guiding us to meet certain people—other fellow Joyceans. It structured where we went, who we met, and also what we saw and what parts of Dublin popped out to us.”

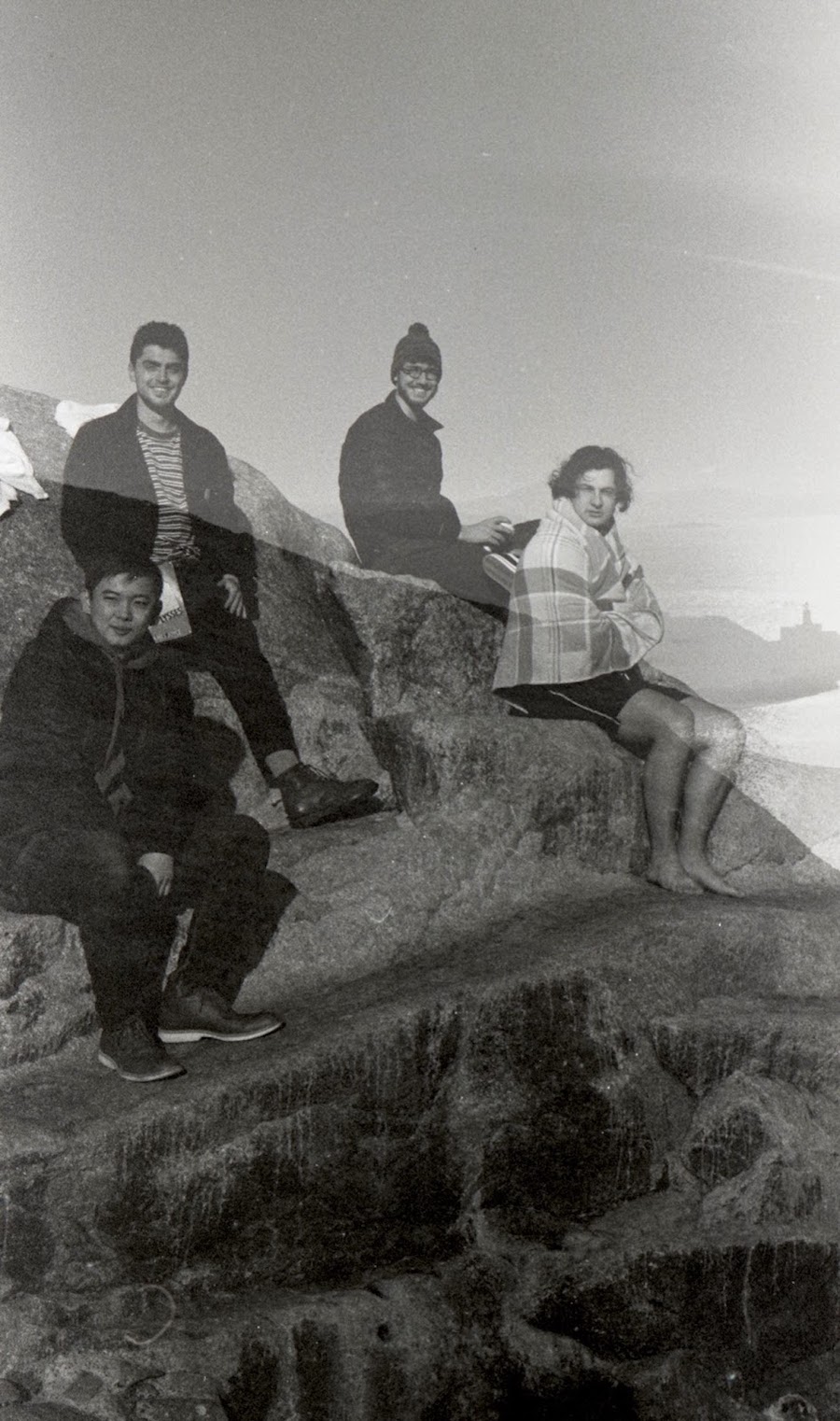

Wackerman documented the trip with his photography. “Max was talking about how the Odyssey was a road map for Joyce, and Ulysses was a road map for us on this Dublin journey,” Wackerman said. “I was thinking about ways to translate this conceptual framework into a visual register.”

In order to replicate and emphasize the message of “double exposure,” Wackerman superimposed many of his photos from Dublin onto one another.

“One of the things that you'll learn when you're reading James Joyce is that it's really hard, and what I strived to produce with these images is a kind of visual difficulty,” Wackerman said. “If there's something that I've learned from Joyce, it’s that illegibility can be a virtue. When you look at these images, I'd like you to consider, ‘What is actually going on right here? Can I distinguish these two images? Are these even one image?’”

Next, Welch discussed the group’s gastronomic experience in Dublin, as well as the Irish social rituals associated with eating and drinking. Chang built off of Welch’s presentation by sharing the small—but meaningful—ways that the group realized the bonds between one another.

“At one point, we decided to go separate ways on our own little journeys, and I decided to return to the place that felt most friendly to me: the bookstore,” Chang said. “There, strangely, I saw, standing in the poetry section, the figure of [Welch]. Somehow, we had both decided to go there.”

Lasarte concluded the presentation with a reflection on the most transferable lessons from the trip to Dublin, as well as his personal thanks for his exposure to the novel, Reizbaum’s instruction, and the College’s support of the five students.

“The question that was following us throughout the entire class was, ‘Why are we even doing this? Why are we reading this ridiculously long, complicated novel?’, and [Reizbaum’s] answer was that his work can teach us something about the sheer illegibility of life,” Lasarte said. “I'm thankful for Ulysses, and I often find myself walking around campus, resting in my Bloom-esque inadequacies, gazing out…at all the different representations of the sheer illegibility of life."