Remote Learning in Remote Times

By Kat StefkoOnline learning descended upon the Bowdoin campus with precipitous speed in Spring 2020, a necessity wrought by COVID-19, which brought normal campus life as we all knew it to a screeching halt.

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Class of 1825 silhouette portrait imposed on 1950-era photograph of the “Rainy Day Room” in the poet’s childhood home in Portland, Maine, from the Collections of the Maine Historical Society.

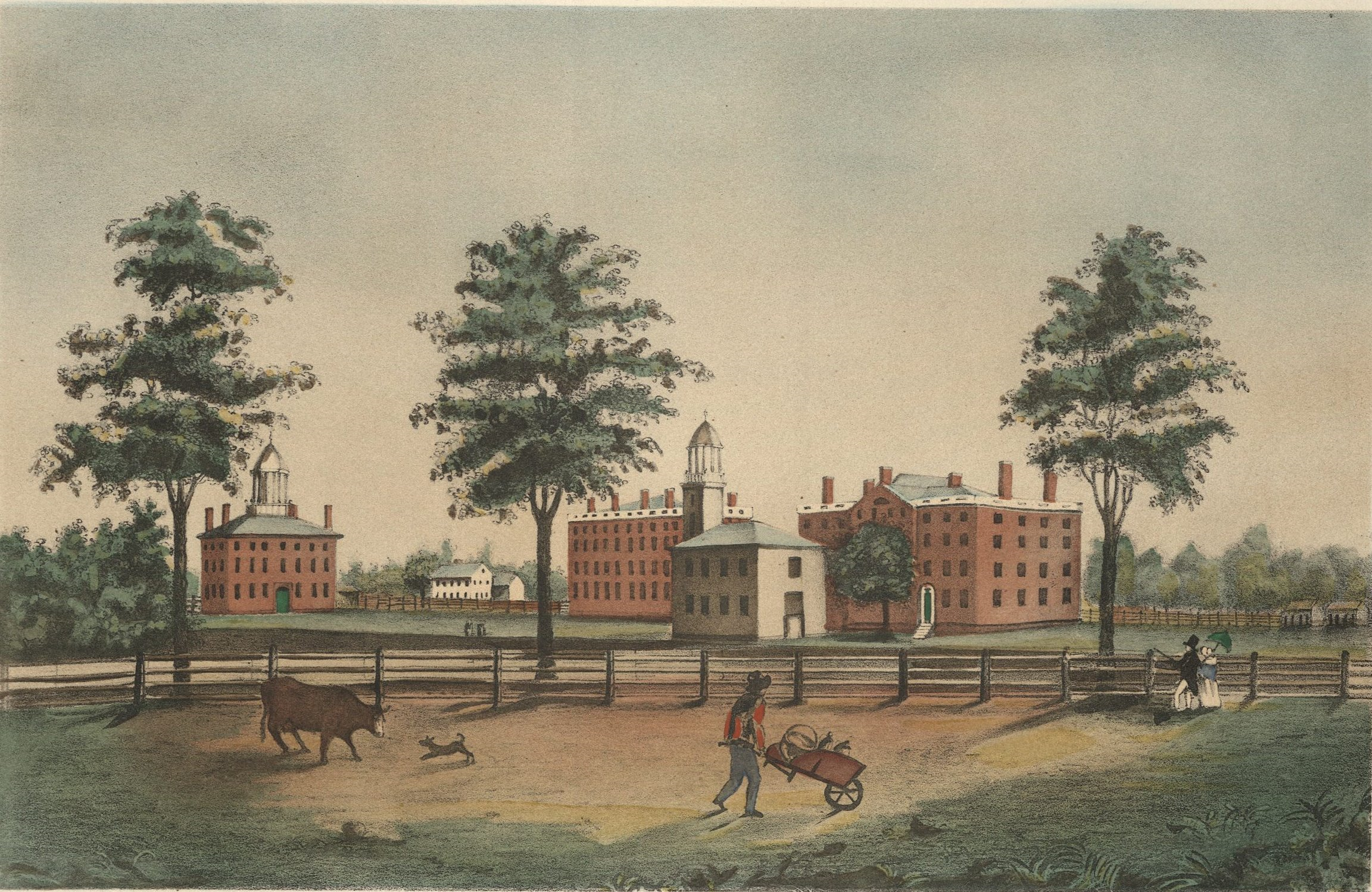

Here is another distinction for our famous Class of 1825: it was the first to embrace hybrid and remote learning. When the Class of 1825 commenced their studies in the fall of 1821, only twenty-three of thirty-five students arrived on campus—the other twelve remained at home to undertake their studies as “distant learners.” I

n years past, the College had permitted perhaps one or two students in each class to study remotely for some period of their academic career, but, for various reasons, the option to learn remotely was commonplace for the Class of 1825. Why? What motivated students to stay home, and why did the fledgling college embrace distance learning as an option?

Unfortunately, the archival record does not answer these questions definitively, but there are some tantalizing clues. The students who opted to stay home for their first year appear to fall into one of two categories: either they were the children of elite, protective parents, or they came from lesser means and needed to help financially support their families.

In the first camp were Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and his older brother, Stephen, both of the Class of 1825. Henry was young for a freshman, a mere fourteen years old when he matriculated, but it seems that it was Stephen’s mischief-making and propensity for trouble that gave Mr. and Mrs. Longfellow the greater pause about sending the boys off to college.

Instead, young Henry and distractible Stephen completed their studies with their private tutor, Bezaleel Cushman, at his Portland Academy that first year. Cushman was a Dartmouth graduate who received an honorary degree from Bowdoin in 1812. Along with the Longfellow boys, Cushman tutored their childhood friend Edward (Ned) Preble, a fellow remote-learning member of the Class of 1825.

The Longfellows’ classmate Alden Boynton, on the other hand, stayed home to keep his family financially afloat. Boynton’s father had been a wealthy shipmaster in Wiscasset but lost everything when Alden was nine. To survive, the family moved to the outskirts of the town and began farming, with Alden taking on much of the manual labor. Writing years later, he recalled:

I attended the district school that winter and two winters following, and the summer school occasionally. But for about two thirds of the year, I had plenty of work to do, the farm and stock being large, and I being the only boy….When I was eleven years old I studied the Latin grammar some…There was about that time and for the first time a high school, so called, opened at the village, and the outer districts could send a certain number of scholars. There were but 2 terms. I attended one of them and read the Latin Primer…Soon after the close of the high school, Mr. P[ackard] kept 2 quarters (twice 12 weeks) of private school, which I also attended and read Virgil and a part of Cicero….I worked diligently and hard… and studied in the long evenings and stormy weather….At 15 years of age in 1821, I entered the freshman class at Bowdoin College, I remained at home another year, pursuing the former method.

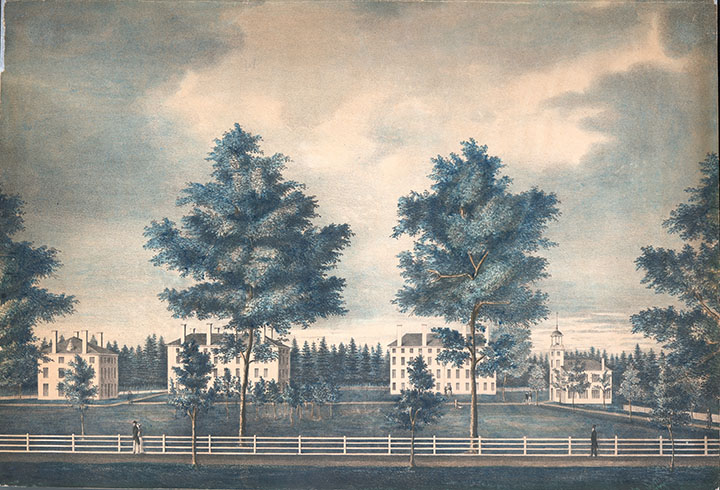

Presumably, the College president and faculty would have preferred that all these young scholars be studying under their watchful eyes, but circumstances required them to think creatively about how to accommodate a growing number of students who wanted a Bowdoin education. Between 1818 and 1821, the student body doubled, jumping from 57 to 114 students by the time the Class of 1825 commenced their studies, resulting in an acute housing shortage.

It is likely that civic pride and general excitement around Maine statehood in 1820 contributed to the uptick of parents wanting to prepare the next generation of state leaders by offering their sons a college education. There was also William Allen, inaugurated in 1820 as the latest College president, and with him, perhaps a change in thinking about class size.

Whether the upward trend in enrollment related to financial matters is less clear. Certainly, the young college had weathered a turbulent decade whereby its finances were jeopardized in succeeding order by the War of 1812, the treasurer’s unscrupulous financial dealings in 1815, and the potential (but eventually not realized) loss of state funding when Maine separated from Massachusetts.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, even more than now, tuition made up a sizable portion of the College’s budget. Yet more students, at least remote ones, did not mean more funds, as they were charged no fees. However, another category of students, boarders, were.

Boarders were students who paid the full tuition and housing fees but lived off campus in a handful of boarding houses. Due to a scarcity of dorm rooms, eleven students from the Class of 1825 had to board with local Brunswick residents their first year.

We will look more closely at the boarding houses later in our series on the Class of 1825, but for now, perhaps today’s Bowdoin students can take heart in knowing that the disruptions endured by the Class of 1825, a full two-thirds of whom did not live on campus their first year, did little to dampen the long-term benefit of their Bowdoin education and the enduring friendships they made while college students.