Seeing Me

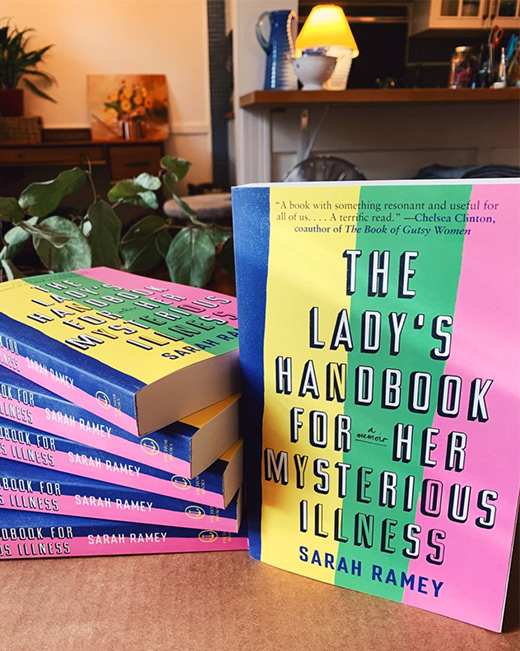

By Jennie AggBeset by crippling pain and fatigue, Sarah Ramey ’03 took nearly fifteen years to write her memoir, The Lady’s Handbook for Her Mysterious Illness. Told by the medical establishment that there wasn’t anything wrong, that her symptoms were psychosomatic, Ramey dove deeply into primary research so she could more thoroughly understand her situation.

What she learned led her on a journey of hope and resilience that represents an all-too-familiar experience for many marginalized people, including women—not being believed.

The afternoon before her life changed irretrievably, Sarah Ramey ’03 took a swim in Walden Pond.

It verges on cliché to write that someone has barely a care in the world just before disaster strikes, but for Ramey it is hard to remember that afternoon any other way. She was about to start her senior year at Bowdoin. She was living with her childhood best friend in a summer rental. As the cool water lapped at her skin, if she was thinking about anything, it was staging ideas for Into the Woods—the musical she was looking forward to directing when the semester began.

In the quieter reaches of the Concord, Massachusetts, pond, away from the snorkelers and day-trippers, Ramey floated on her back, staring up at the wide blue sky. Everything was ahead of her. A creative life in New York, perhaps. Interning at a magazine. Or submitting demos of her music. Almost certainly some waitressing on the side. She was, she says, “planning on making plans.”

What happened instead started innocuously enough. She came home from Concord with a urinary tract infection that a following course of antibiotics did not touch. It should have improved within twenty-four hours, the emergency room doctors told her. In fact, as Ramey explains in the introduction to her memoir, it did not go away for six months.

This story might start in Thoreau’s backyard, but it quickly crosses over into the topsy-turvy realm of Lewis Carroll. Back home in Washington, DC, for the Christmas holidays, Ramey made an appointment with a top-notch urologist, who decided then and there to make a tactical rip in Ramey’s urethra—a disastrous decision—to “break the cycle of pain.”

Shortly after, she developed sepsis—a systemic overreaction to an infection that can lead to organ failure. Ramey recovered from the sepsis, but now there were new problems. Aching. Daily fevers. Itching. Excruciating “broken glass” pelvic pain. Intestines that felt like they’d been piped full of cement. Brain fog. Fatigue.

After the winter break, “it all fell apart,” Ramey says. She returned to Bowdoin with painkillers and a portable IV for more antibiotics. But she got worse, not better. She saw a nurse and doctor on campus, who both said her case was too complicated to treat locally and that she needed the help of her specialists back in DC.

In her memoir, she writes: “I was on so many medications and getting so sick so fast, it was like a rabbit hole had opened up beneath me—that I was falling slowly past the clocks and candlesticks, and that my parents and doctors were peering over the edge, quietly watching me float down and away.”

So began Ramey’s eighteen-year voyage of baffled specialists, inconclusive tests, and many invasive and ultimately unsuccessful procedures. She would be prescribed medications to do one thing and her body would do the complete opposite. Over time, she would be told—both by conventional medical doctors and alternative practitioners—that because they could find no cause for her illness, it must be in her head. She just needed to try a different antidepressant. Or a more positive mental attitude. She dutifully tried both. She kept getting worse.

Ramey kept falling: out of a normal life of beach trips, boyfriends, performing, and spontaneity; out of sight, confined first to the house and then eventually to her bed; out of medical answers. But—as she puts it, with wry defiance—“they sent the wrong girl down the rabbit hole.”

Today, Ramey is not just an author but a successful singer, known as Wolf Larsen (her Nebraskan grandfather’s name). The daughter of two doctors and the granddaughter of a pioneering, feminist endocrinologist, she was better equipped than most when it came to navigating the underworld of modern medicine. As a writer, she also had the skills to report what she found there.

It is not a straightforward story to tell. There were several false dawns, a panoply of diagnoses, and absolutely no miracle cures. Ramey still lives with a constellation of complicated and poorly understood chronic conditions, including complex regional pain syndrome, myalgic encephalomyelitis (sometimes referred to as chronic fatigue syndrome or ME/CFS), and postural tachycardia syndrome (POTS—a disorder of the autonomic nervous system, which controls unconscious bodily functions, such as blood pressure and heart rate).

Yet her health is tangibly better than during what she terms her “Great Crash” of six years ago. At that lowest of low points, she could barely move, had to use a wheelchair, and spent most of her day on the bathroom floor, curled in a nest of blankets. Her digestive system could only tolerate broth and juice, which often had to be fed to her by her mother. Anything but total isolation was too much for her.

Today, Ramey is well enough to sit at a desk and write, she can sing (“my old standby medicine for the soul”), eat real food, do gentle yoga, and very occasionally visit a museum or café. But she still has to be careful in ways few healthy people could imagine. “I have to budget my energy like the stingiest miser,” she explains.

It is far from a soaring, sunlit recovery. Ramey’s vision—and mission—is bigger, though. While she says it is “an absolute victory that I got out of that deepest, darkest hole,” the true purpose of her writing is to make a whole spectrum of mysterious conditions better understood; to make the invisible visible.

Through painstaking research presented alongside her own painful experience, Ramey attempts to connect the dots between apparently disparate chronic conditions, such as the pain disorder fibromyalgia, ME/CFS, post-treatment Lyme disease, non-celiac gluten sensitivity, and various shades of autoimmune disease, such as lupus, the bowel condition ulcerative colitis, and Hashimoto’s (a disease of the thyroid gland).

Fifty million Americans have some kind of autoimmune disease, according to estimates by the American Autoimmune Related Diseases Association. It takes, on average, consultations with five doctors before a correct diagnosis is made. Meanwhile, ME/CFS has been labeled “America’s hidden health crisis” by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, affecting as many as 2.5 million people.

What such conditions tend to have in common is that their key symptoms—pain, debilitating fatigue, and clouded thinking—are hard to measure in any objective way. They have no biomarkers. They cannot be scanned or biopsied. They’re also not necessarily visible from the outside: a common refrain for patients is, “But you don’t look sick!”

It’s a phrase Ramey has heard often, one that gives away how narrow our view of illness can be. In fact, in the early days of Ramey’s mysterious illness—pre-crash—people often commented on how well she looked, in part because of changes she’d made in an attempt to heal herself: no sugar, no dairy, no gluten, lots of yoga and green juice. It was, as she writes in the book, perhaps “the most complicating factor of all. Not only was I slightly radiant but, because of the pain in my central cavity, I was always, always in some kind of flowing, pretty dress. More than a few doctors implied that, whatever seemed to be the problem—it suited me.”

“There are a lot of illnesses that are very serious but invisible,” Ramey says. This cloak of invisibility—the veneer of wellness—means they are overlooked, underestimated, and underfunded. She gives the example of ME/CFS, which was found by a 2020 study to be the single most neglected disease relative to the condition’s burden. The authors suggested that NIH research funding into the illness would have to increase fourteen-fold to be in line with the severity of impact on ME/CFS patients’ quality of life. Speaking from experience, she says: “At its most severe, you just feel like every hour you’re going to die. You can’t move. You can’t eat anything. It’s almost like a living death.”

Yet Ramey’s book is no misery memoir. She never lets the reader stay in darkness and difficulty for too long. There are bemused, self-deprecating jokes and strategically deployed puns. She christens the many, many doctors she sees with nicknames like “Dr. Vulva,” “Dr. Bowels,” and “Dr. Oops.” She actually began writing in “a more typical memoir voice: this wistful, sad, unendingly sorrowful retelling.” She threw those early drafts out. “I thought: this was not who I am. And it doesn’t work for the material.” She thought a story like hers—“that has these difficult, confronting, vaginal, poop-related things”—needed the “leavening agent” of humor. She also saw it as an act of kindness to her readers, many of whom she assumed might be similarly sick. “I wanted to be honest and unflinching about the really bad stuff, but to take care of the reader also, and make sure that they’re not being too brutalized, triggered, or traumatized.”

For readers, the jokes serve as kind of a nod to camera, a knowing eyebrow that says, Listen, I know how mad this all sounds. Because possibly the strangest facet of illnesses like Ramey’s is not a lack of detailed, evidence-based understanding, although that’s true—it’s that many physicians still don’t believe they exist at all. Or they remain convinced the symptoms are psychosomatic.

Ramey recalls in her book how she was warned by doctors not to say she had fibromyalgia. “Fibromyalgia, they explained, is just code for ‘crazy.’” A survey of primary care physicians in Connecticut in 2010 found that half did not “believe” in the concept of chronic, post-treatment Lyme disease. Even Ramey’s own doctor parents were skeptical about some of the diagnoses and experimental treatments at the beginning of her health crisis.

Why, though, should such skepticism exist on an apparently industry-wide scale? Why are certain kinds of illnesses downplayed and dismissed? According to Ramey, this is the least mysterious thing about these conditions. “It’s because they really disproportionately affect women,” she says. At least 75 percent of autoimmune disease patients are thought to be women. ME/CFS affects four times as many women as it does men. Between 80 and 90 percent of people with fibromyalgia are female. There is also some evidence—albeit limited—that post-treatment Lyme disease may be more prevalent in women.

Medicine has a long tradition of ascribing physical symptoms to women’s instability. From the Ancient Egyptians and Greeks, who believed unexplained illness in women was caused by a “wandering womb,” to Freud, who gave us the idea that psychological disturbance could cause physical symptoms, hysteria has been used as a diagnosis to cover all manner of mysterious and inconvenient female complaints, from difficulty swallowing to a swollen stomach. The term wasn’t completely expunged from medical textbooks until 1980.

“It’s really difficult for me to imagine these patients being male and it being shoved into a closet,” Ramey tells me. “I just don’t think that would happen.” Later, she reflects: “I don’t think doctors realize how damaging it is psychologically to sense that your doctor thinks you’re lying to them. You can’t blame the patient because you don’t understand something.”

How Ramey's life has changed since Bowdoin is something she thinks about often. She sang in an a cappella group. She directed a musical. She wrote for the Orient. She kayaked on the weekends. “Bowdoin was the best time of my life,” she says. “I made wonderful friends. I was super active. I have the fondest memories.”

And now? “I do feel very, very different to the person I was in college. It is a strange disconnect. I walked through the wardrobe—through the mirror—into a different world.” She likens her medical odyssey to witnessing a war. To then have to “drop back into regular society feels strange.”

Something about this piece feels different from other press coverage for her book, she tells me—more exposing, perhaps. “I so long to just be the person I was on track to be,” she explains. “Thinking about this story in the context of Bowdoin is a wistful, sad feeling. Because I remember exactly what I thought was going to happen. I know everybody’s life turns out differently to how they anticipated, but usually not like this.” She laughs easily as she says it—as is her habit—but “this” encompasses a lot of near-unimaginable pain and trauma. Having nerve-stimulating wires embedded in her pelvis by one doctor without her knowledge or consent, for one thing. (That would be “Dr. Oops.”) “But then, in a lot of ways, I am still the same,” Ramey adds. “I’m making music and writing—those were the two things I wanted to do in college. I cannot believe I ended up doing both of them.”

In the early days of being unwell, creativity was an outlet for Ramey when there was little else available. Despite being unable to tour, or even to perform with any regularity, an album Ramey made from her bedroom in 2011, Quiet at the Kitchen Door, has been listened to more of than 50 million times on YouTube. In her book, she describes the peculiar sadness of watching her Wolf Larsen avatar go viral, in lipstick and heels, while she was back in the house she grew up in, rarely out of her nightgown. “From an invisible cage, I gripped the bars and watched as my windup-self took on a life of her own and moved on without me,” she writes.

Now, though, her creative life and the reality of her illness seem to have found more of a symbiosis. Ramey recalls how Joan Didion once said in an interview that writing was the only way she could be aggressive, as a physically slight, quiet person. Ramey tells me her equivalent is that the page allows her to feel safe in a way that real life often doesn’t. “I feel like I can say what is true for me, and it won’t boomerang back on me in a negative way—the way it might at the doctor, or with an acquaintance who doesn’t believe in ME/CFS. On the page you have plenty of time to say exactly what you mean, and say it as forcefully as you like.”

A striking feature of The Lady’s Handbook for Her Mysterious Illness is its generous use of white space; the text fragmenting into short paragraphs, lists, and single-line phrases. The effect is poetic and punchy. And it’s a creative decision that’s a direct consequence of Ramey’s physical symptoms, as the terrible brain fog she has makes it hard for her to read dense, unbroken passages of text.

“I started breaking things up because it helped me to not get overwhelmed,” she explains. “And then I realized I liked that style—it actually made it read faster and that would be helpful for somebody like me: to break it up as much as possible, to keep that narrative motor running. That’s the only type of book that I can read anymore, something that’s really fast-paced.”

It works. Her book is described by Publishers Weekly as both “hilarious” and “illuminating,” and has been lauded by Chelsea Clinton and Ann Patchett, among others. However, as Ramey has discovered, there is a certain irony to acclaim that comes from writing a manifesto on invisible illnesses that people don’t take seriously: it can mean people don’t take your own invisible illness as seriously.

“The thing I struggle with the most is to make my actual reality legible to other people,” she tells me. Visible professional success tends to work against this. “It creates this exterior picture that things are great,” she says.

The reality is that she could only write for an hour a day. After that she could do little else but sleep for the rest of the day. “I often felt like I was making myself worse in order to write about my illness,” she says. She wrote the book from bed, on an elaborate arrangement of pillows to keep the pressure off of the “white-hot pain in the spine, bladder, ovaries, rectum, vagina, and left leg.” While writing, she was also competing in what she calls the “Bowel Olympics,” running to the bathroom every ten minutes. “This is a sub-optimal way to write a book,” she quips.

Ramey also resists the idea that her exterior success somehow makes everything she’s been through worthwhile. “The things that people say are just wild,” she says. “‘Aren’t you glad you went through all of these horrible things so that you could make this new record, so you could become Wolf Larsen, so you could write this book?’ And the answer is a hard no.”

She later clarifies: “There is no doubt I have grown in many ways because of my illness—I have more empathy, I have more perspective, and I am stronger. But would I do eighteen almost unbroken years of severe suffering over again? Absolutely not. Would I wish what has happened to me on a single human being, in the name of growth? Absolutely not. This is the tyranny of positive thinking—that everything has to be good, golden, inspirational, and everything has to happen for a reason.

“There is so much pressure on the disability and chronic illness communities, narratively speaking, to fight, to overcome, to be the winner—or alternatively, to be the most grateful, the most accepting, the most serene. For some, this is very empowering and I deeply respect that. But from my perspective, it’s also empowering to say, ‘No, thank you. I don’t accept this, and I don’t want it. Not for me, and not for anyone else.’ It can be empowering to draw meaning from the struggle to change the systems that cause us harm, even if we can’t change our own illness.”

When Ramey and I speak for this interview—the old-fashioned way, on the phone rather than over Zoom, because she finds screen-free more manageable—it’s been just over a year since her book came out on March 17, 2020.

“We were right in the middle of confirming appearances on big TV shows and a feature on NPR when it became clear that the world was about to change, and all those appearances were canceled. Having worked on the book for [so many] years only for it to come out at that moment was gutting.” (Although, she jokes,

it felt “very on-brand” to have a book about mysterious, overlooked illnesses dwarfed by a global pandemic.)

For Ramey, day-to-day life has been “almost exactly the same” under COVID-19. “It’s so strange to have had this one year where all of a sudden everyone has had all these things in common with me,” she says. “But there’s also sadness there, because they will go back to all of the things that they do in their life. There’s a long goodbye coming for the rest of us that have to stay behind.”

Of particular interest to Ramey is the so-called long COVID, where people apparently recover from the initial viral infection but continue to have debilitating symptoms like joint or muscle pain, extreme fatigue, unexplained fevers, and brain fog. It has been surreal, she says, watching the long COVID story play out in real time and seeing how these patients—with mysterious, unexplained, and chronic symptoms that feel instinctively familiar to her—have been treated. “The acutely ill [with COVID-19] are treated as a huge emergency, of course, which is as it should be,” she says. “But the post-COVID people are treated pretty poorly. If you have COVID-19, everyone is doing heroic work to take care of you and to make you well. And suddenly you walk through the mirror: you’ve got long COVID and you’re in a complete shadow-land where everything is different. Up is down and left is right. Nothing is making sense, nobody is trying to help you. And you can’t figure out what is wrong with you.

“It’s a very disorienting experience—as I’ve obviously experienced—because you’re the same person that was being treated like an important person a month ago, and now as this liar, malingerer, hypochondriac. But you’re not acting any differently as a human being, you’re not hysterical, you’re not reporting things any differently, you’re not using a different tone of voice.

“It’s just that the stigma of this kind of illness is so incredibly strong it doesn’t matter how you behave,” she says. Ramey’s hope is that the intense spotlight provided by the pandemic will mean that a more unifying understanding of chronic illnesses emerges. A good start is the $1.15 billion that’s been allocated for the NIH to research long COVID.

“It’s hopeful,” she says. “Because it’s such a large, loud influx of patients all saying the same thing, I think it’s more difficult to dismiss.”

Jennie Agg is a UK-based freelance journalist who specializes in women’s health. She is working on her first book.

Julius Schlosburg is based in Tucson, Arizona. See more of his photography at jpopphoton.com.

Listen to Sarah Ramey '03 interviewed on NPR's "Morning Edition," July 23, 2021.

This story first appeared in the Spring/Summer 2021 issue of Bowdoin Magazine. Manage your subscription and see other stories from the magazine on the Bowdoin Magazine website.