Ben Butler ’00 and the Pull of Public Art

By Rebecca Goldfine

During his senior year at Bowdoin, Butler got an impulse he says he only began to understand many years later. In the weeks leading up to graduation, he borrowed 128 railroad ties from a local lumber yard. Hoisting the heavy timbers by hand, with a rotating group of friends, he constructed a series of "stacked minimalist sculptures" on campus.

A few days later he dissassembled the tower, only to reassemble and restack it somewhere else. Then he did this several more times. "They were big pop-up installations," Butler said. "I realized that this was an exciting kind of art for me—exciting in that it wouldn't ever exist in a box or a gallery."

These days, Butler is continuing to push the limits of his career and his art. Since leaving a teaching post at a college in Tennessee, he's been creating large-scale installations in public spaces across the country. Many of these works suggest a kind of boundlessness or endlessness; they take on forms that one could imagine might continue indefinitely into space.

For instance, in a wall sculpture he recently completed for a biotech research facility in Wisconsin, wooden atom-like shapes, though static and fixed, appear to be generating and shedding particles that drift away. In another sculpture, The Wanderer, made from transparent acrylic, serpentine filaments seem to ripple through the air, expanding outward like noiseless radio waves.

Butler actually intended these ribbons to mimic the twists and turns of the Mississippi River, and to evoke the long timeline of its shifting shape and course. "Inspired by geological surveys of the Mississippi River’s meander belt, The Wanderer tracks the path of the river over time, with each layer of the sculpture representing roughly a century of change," he explains.

Butler repeated a comment he was told at a gallery opening: "Someone once told me, 'When I look at your work, I feel like I am staring through a lens, but I don’t know if it is a microscope or a telescope,'" he said. He liked the observation because "it implies ambiguity of scale."

"In all of my work, I am really trying to look more closely at natural processes, so things like magnifying lenses and telescopes are ripe territory for me to explore imagery," he added.

Three Recent Sculptures by Ben Butler: Gathering, The Wanderer, Old Growth

"A Deep Dive" into Public Art

After teaching at Rhodes College in Memphis for seven years, Butler left academia to dedicate himself to making art for public spaces. "Public art is a really good fit for my work, for a lot of reasons," he said in a recent Zoom call from his workshop in Memphis. He's lived there since 2008.

His current vocation occasionally causes him to reflect back to his twenty-two-year-old self, when he stacked railroad ties on Bowdoin's Quad. "Now I am coming full circle to putting art in public places, where the audience isn’t quite known, where people are not showing up to find art, but they stumble upon it or are confronted with it," he said.

Public art is compelling to him, he continued, because he wants to create work that encourages people to interact with it spatially, to move through it, to meander. At the same time, public art comes with limitations—both physically, based on space constraints, and thematically, based on the need or mission of the organization. He appreciates these limitations. "It's like an assignment or prompt," he said, that pushes his imagination in different directions.

Competing for art commissions has also made Butler more apt to verbalize his intentions, something he had not felt necessary in the past. "So much of my work is non-linguistic and vague, but when you are presenting a proposal for public art, you are asked to name it, and to explain yourself," he said. This has led him in many instances to make more explicit the link between his creations and the natural world.

"There is this kind of responsibility with public art. You want to make it accessible in a way that is not pandering, but that is generous and inviting. There is a balancing act there—you don’t want to do something people have seen before, but you do want to invite them in, and then challenge them." — Ben Butler

His focus on the natural sciences stems from a lifelong curiosity about the natural world and how things grow and come into being. And he originally arrived at Bowdoin intending to study biology or neuroscience, since he was also interested in how the brain works. But he dedicated himself to art when he realized he didn't have to give up his exploration of science.

"I really found art to be this kind of perfect vehicle for incorporating all my interests," he said. Faculty like Mark Wethli, who is Bowdoin's A. LeRoy Greason Professor of Art, and John Bisbee helped him broaden his ideas of what art could be.

"I remember the first semester I took Drawing I with Mark Wethli, and right away it shifted my perception of what art might be," Butler said. "Previously, I had some notion that art might be limiting, and I thought of drawing as a finite discipline, but Mark was talking about literature and music and poetry and science throughout the course, and he was presenting drawing as this way of thinking—that it is a wide-open medium, a language for doing anything."

He found the same approach in his classes with Bisbee, and soon after, "felt comfortable dropping" his neuroscience major.

With Bisbee, he also "found a natural affinity with sculpture as a medium. In particular, Bisbee's mode of working was based on a commitment to abstraction, and his process involved slow accumulation, sometimes to the extreme. This became the foundation of my aesthetic as a sculptor," Butler said.

"John also modeled such an intense devotion to work and showed me what it meant to put my art ahead of everything else, something that I was previously very hesitant to do."

After Bowdoin, Butler earned his MFA at the Art Institute of Chicago, in the city where he grew up. After completing this program, he set up a studio on Long Island, New York, with his wife, oil painter Laurel Sucsy '98, before moving to Memphis to begin his teaching job.

Since turning most of his attention to public art, Butler has hired a couple of employees to help in his workshop. "As I got into public art, I made a very deliberate decision to dive into the deep end," he said. During the first few months following his resolution, he scoured national postings for art commissions. "I told myself if I applied to 100, I would probably get one."

As it turned out, he applied to fifty and was a finalist for six. Though he didn't get any of those original six, he's since completed more than a dozen public sculptures, just about three a year, in Tennessee, New York, Georgia, Illinois, California, and Wisconsin.

Work remains steady. This summer, he will install a wall sculpture at the Portland International Airport in Oregon that will "be an homage to the lumber industry and the Douglas fir forests of the Pacific northwest," he explained. The proposed piece (rendering below) will be made from recycled wood from demolished buildings in Portland.

He is also currently working on a hanging sculpture and wall installation for a new science building at the University of Wyoming, which houses a number of electron microscopes. "In my proposal, I was looking at the ways that science generates images to help us understand things," Butler said.

The piece is "derived from electron microscope images of human neurons," which Butler turned into an abstract drawing before transforming again into a massive wooden wall sculpture.

Focusing on public art has changed Butler. While it's made him more agile in business, it has also transformed the way he thinks about art, how it is made and what it is for. "There has been a major psychological shift for me in telling this mythology around how art is made," he said, in "that it is private and needs to be protected, that it involves a special process."

Instead, he now views it as improved by collaboration, conversation, and openness. "For years, I just told myself I am going to make what I want to make and find a place for it in the world, but I have turned that upside down," he said, a turn he attributes in part to his age and to raising children (he has two, ages eleven and nine).

"The first question I ask now is not, 'what do I want to make?' But, 'what is needed here, and how can I contribute?'" he said.

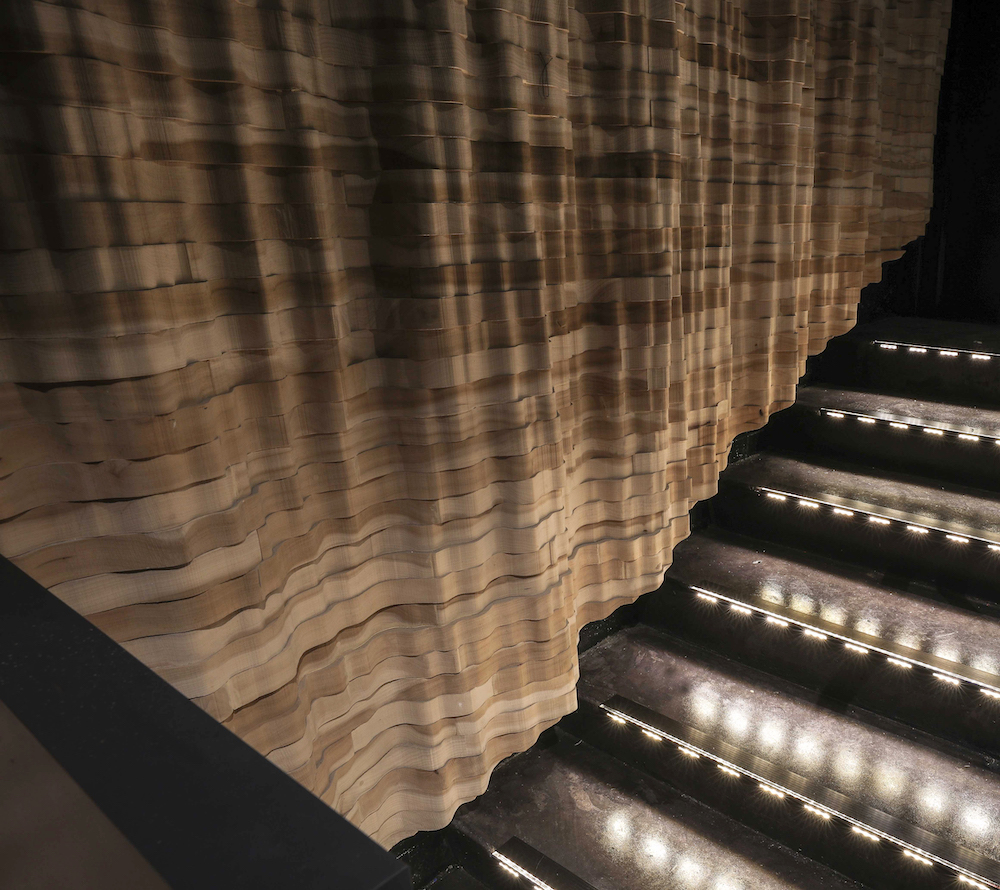

Three years ago, Butler was helping to set up a woodshop for a new artist residency in Memphis. An acoustical engineer saw his work and started to chat with him about textured wood panels and how they might be adapted into acoustic diffusion panels. This led Butler to a job building a new performance space, as well.

"I did this project where the entire interior of the theater is solid wood, these organic forms that are like my other work, based on line drawings. I worked within the parameters the enginer told me would diffuse the sound evenly. So the walls are functional."

The wavy textured walls maintain the volume of sound from the stage and help distribute it evenly throughout the theater. "That art project was a really interesting overlap with music and physics," Butler said.