Why Would Anyone Want to Be President?

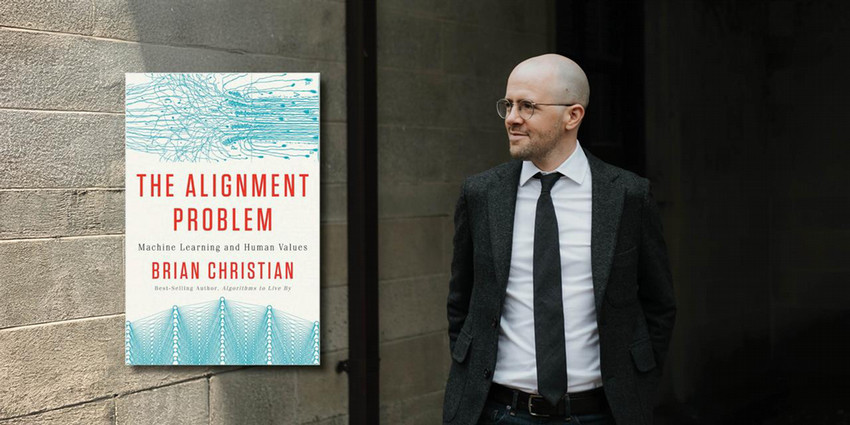

By Tom Porter“Can the president launch a nuclear attack without congressional approval? Is it ever a crime to criticize the president? Can states legally resist a president’s executive order?” These are some of the questions posed in Corey Brettschneider’s latest book, The Oath and the Office: A Guide to the Constitution for Future Presidents.

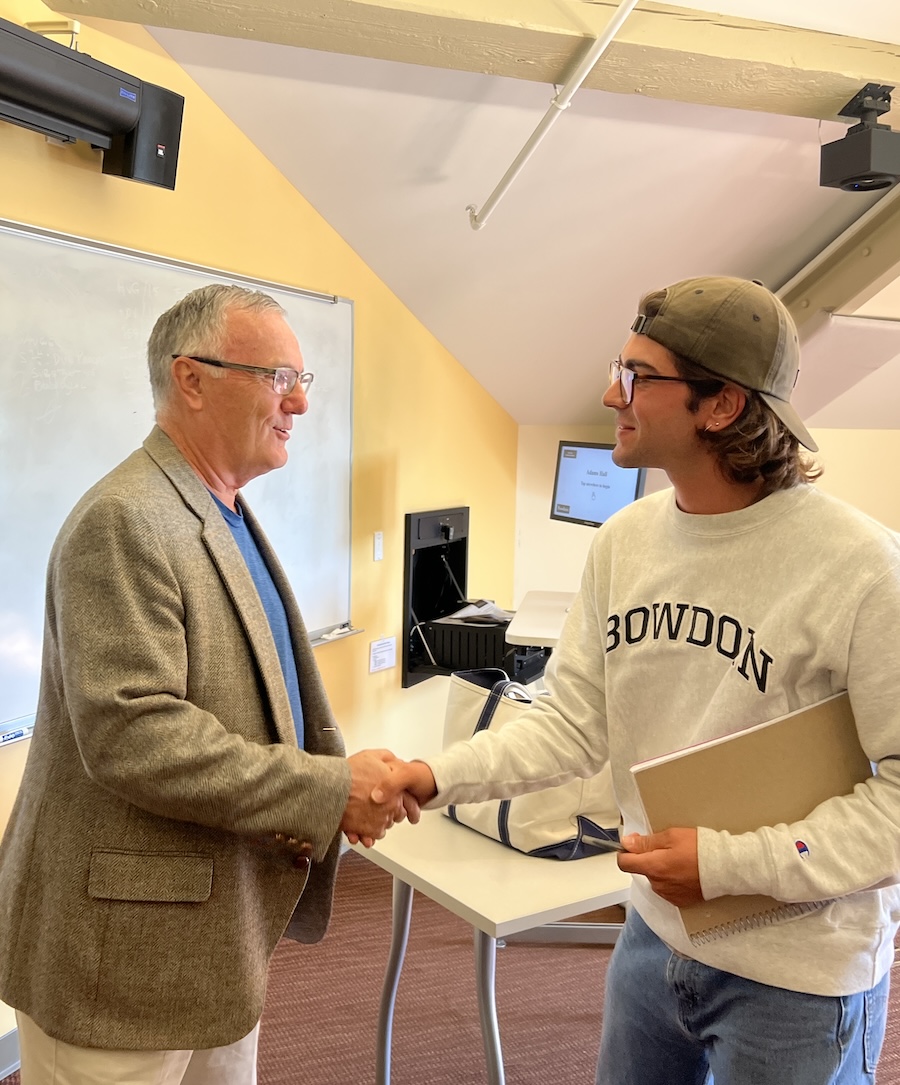

As this year’s Carl F. Cranor Phi Beta Kappa Visiting Scholar, Brettschneider paid a virtual visit to the Bowdoin campus recently to meet with students, with faculty, and with President Clayton Rose and to participate in classes and seminars. He also delivered a talk to the Bowdoin community on March 8. He began the event, moderated by Thomas Brackett Reed Professor of Government Andrew Rudalevige, by asking another question: Why would anyone want to be president?

“You get to travel on Air Force One and live in the White House,” said Brettschneider, a professor of political science at Brown University. On top of that, he explained, as president you would get to try to enact your own policy goals, maybe reshaping foreign policy and America’s place in the world. “Or you might just be thinking over the past four years, pretty much every day, ‘You know what? I think I might just be better at this than the current incumbent.’”

Brettschneider soon made it clear, though, that he wanted to talk about a very different idea of the presidency, one that is embodied in the oath, found in Article II of the Constitution, sworn by every incoming president: “I do solemnly swear that I will faithfully execute the office of the President of the United States. And will to the best of my Ability preserve protect and defend the Constitution of the United States.” It’s a legal and constitutional requirement that every president swear this oath,” he explained. “Notice the president is committing not to just do a good job or implement policy or cater to a political constituency, but to preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution of the United States.” In other words, he continued, the oath is “a symbol of the idea that a president cannot do anything he or she wants, but is constrained by the duties laid out in the Constitution.”

Despite such constraints, said Brettschneider, presidents still have considerable freedom in how they act and speak. Being president, he said, involves pulling off a delicate balancing act between upholding the values of the Constitution and protecting people’s First Amendment rights to all viewpoints—even ones that are antithetical to those values, such as white supremacy. Presidents are expected to use this “bully pulpit” responsibly, and not all of them have done this, he added, including, notably, the forty-sixth president, Donald Trump.

“One of the worst moments of the last four years was in Charlottesville when the president talked about there being good people on both sides. This wasn't just a bad statement,” said Brettschneider, “it was to my mind a failure of the duty to condemn opponents of the Constitution even while, and this is the tricky part, we don't imprison them. We protect their rights to free speech.” This is a principle that won’t be enforced by the courts, he said, but one that the president should uphold if he wants to adhere to his oath of office.

Watch Brettscheider’s talk:

Professor Corey Brettschneider’s visit was sponsored by Bowdoin's Phi Beta Kappa chapter as well as the Department of Government and Legal Studies, with support from the John C. Donovan Lecture Fund.